Beethoven gets seriously serious

mainWelcome to the 53rd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

String Quartet No. 11 in F minor, Op. 95, ‘il serioso’ (1810)

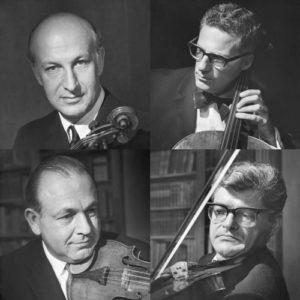

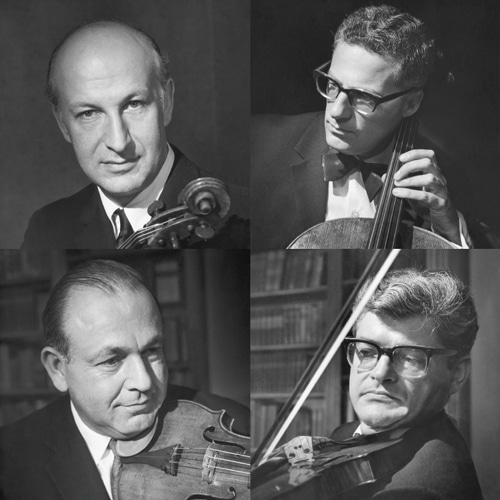

When I first met the Amadeus Quartet they were in advanced middle-age and in no mood for banter. At a photo session for the Sunday Times magazine, one of them burnt the sleeve his jacket on the bright lights and was muttering about damages. The other three could not get out of our studio fast enough. There was not much I could say or do to lighten the atmosphere. I registered them at the time in my young mind as ‘the serious quartet’, not relising that there happened to be a work of that name by Beethoven, or that all string quartets are pathologically serious when it comes themselves and their work. Show me a smiling string quartet and I’ll hazard a guess they are about to break up.

Over time, I got to know the Amadeus better, meet their wives and heard about the struggles they had endured to become the premier quartet of their time. Three of them – Peter Schidlof, Siggi Nissel and Norbert Brainin – met as Austrian Jewish internees in British wartime camps for enemy aliens. The fourth, Martin Lovett, got connected through their teacher in London, Max Rostal. They formed the quartet in 1947 and named it just in time for a January 1948 debut at the Wigmore Hall.

Forming a string quartet is tough and, initially at least, unrewarding. The travel is arduous, the hotels uncomfortable, and the fees have to be split by four. Most quartets break up in the first couple of years on the road. The Amadeus were just starting to make records on British Decca when Elsa Schiller, head of Deutsche Grammophon, heard them in Berlin and signed them to her label. Elsa was a survivor of the Theresienstadt concentration camp. She was looking for a counterweight to some very well established German quartets with an unpleasant Nazi record. The Amadeus fitted the bill.

They became DG’s go-to quartet for core classics. Their 1952 recording of the Serioso has a raw contrariness that rubs against the grain of their sleek and unmemorable competitors. The stereo version of the Serioso in 1960 is, if anything, even more muscular and self-assertive while achieving a transcendent ethereality that helped define their style.

Back in England, they persuaded Benjamin Britten to write them a quartet but they showed scant interest in other new music. Playing classics was hard enough if they were to maintain supremacy in an incresingly competitive field with crack American and Russian groups crowding out the racks. The Amadeus had just signed on to record a second Beethoven cycle for DG when, in August 1987, the violist Peter Schidlof suffered a fatal heart attack on a Sunday afternoon in the north of England. ‘He was the one who was least often satisfied,’ said the critic Bernard Levin. The group could not continue without him.

Forty years is a long time for a string quartet to last, and the Amadeus defined their era. For those who got to know them, they were intensely human in all their transactions, dedicated to their craft and without a patina of the vanity that disgraces many classical stars. In the ‘serious’ string quartet, they were at once appropriately solemn and, if that can be imagined, just sufficiently distanced from the work to suggest an undercurrent of shared dissidence, ambition and exaltation. I can never listen to the 11th quartet without thinking of them and what they brought to the artform.

The 11th is the shortest of Beethoven’s string quartets, barely 20 minutes long. The composer wrote to an English musician, George Smart, that he intended it for serious people, ‘never to be performed in public’. It has a tight-lipped, stern expression and does little to ingratite itself with players or listeners. Gustav Mahler considered it one of Beethoven’s most progressive works and made a controversial version of it for string orchestra. Other musicians have found in it far-fetched theories of liberation theology and cosmic Buddhism. Taken seriously, it offers much food for thought. It is the last quartet Beethoven wrote before entering his transcendental final stretch.

I have to make a cup of tea and walk three times around my loft space before I can banish the Amadeus from memory and listen to other contenders. The Koeckert Quartet, for instance, established 1939 as the Sudeten-German Quartet with all four players landing post-War jobs for life at the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. They have the luxury of being able to relax into the life of a string quartet and lack the existential edge of the Amadeus. In the Serioso they sound almost dismissive of the title, searching for a sweetness of tone and an idea of beauty of a very German, nature-based kind. There is an unarguable autheticity to their approach; the rest is a matter of taste.

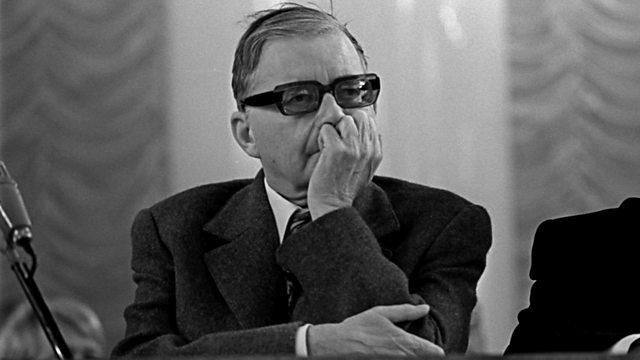

The all-Russian Beethoven Quartet are positively brutal in their attack. There is an edge to the tone that would offend bourgeois ears and a thrust that calls to mind the momentum of their close associate Dmitri Shostakovich. Yet the closing Larghetto of this quartet is as serene and consolatory as any music one could call to mind.

The Alban Berg Quartet (1999), no less wonderful, import many shades of modernism to their art of interpretation. Technique and precision are faultless and one is left gasping at the effects they bring off. The US-based Emerson Quartet – Eugene Drucker, Philip Setzer, Lawrence Dutton, David Finckel – are in the same elite class, treating Beethoven with respect but not as a challenge to their abilities. The apparent ease of their playing can occlude the depth they achieve in presenting the work in its full colours. I am in awe of this performance.

Among recent recordings, the Prague-based Smetana Quartet (2018) exemplify a central-European tradition of strong statements backed up by powerful emotions. The Kuss Quartet (2019) sound emollient by comparison. Short as the quartet might be, it offers multiple avenues of exploration.

Are you still hankering after the Mahler adaptation? Don’t say you haven’t been warned. This is Yuri Bashmet souping it up with the Moscow Soloists. Christoph von Donhanyi with the Vienna Philharmonic is the de-luxe brand, immaculately groomed.

Comments