Welcome to the 60th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

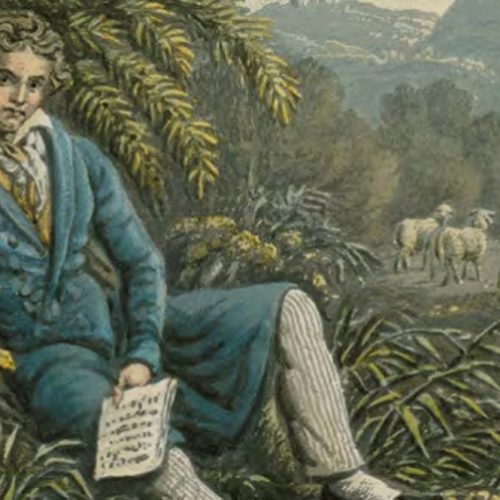

Pastoral Symphony (part 2: click here for part 1)

Beethoven’s sixth symphony was the first to tell a proper story in music, about a day out in the country. That opened a window to an entire century of symphonies with programmes attached. But it also set the tone for future pastoral masterpieces by Brahms (symphonies 2 and 3), Bruckner (4), Mahler (1, 3 and 7), Elgar, Vaughan Williams and many more.

Beethoven’s other striking innovation is that this symphony breaks the Haydn four-movement straitjacket and sprawls across five. By now, Beethoven was not bothered by convention. Almost totally deaf, he could not hear criticism and never read reviews. Unusually, it ws he who gave the symphony its name. He also provided a brisk summary of what listeners could expect:

Pastoral Symphony, more an expression of feeling than painting. 1st movement: pleasant feelings awaken on arriving in the countryside. 2nd: scene by the brook. 3rd piece: merry gathering of peasant, interrupted by 4th: thunder and storm, yielding to 5th: salutary feelings combined with thanks to God.

Beethoven is supposed to have said: ‘I love a tree more than a man’. Yet that is not the impression we get from the music. We sit back and appreciate nature without wanting to hug it. What we hear is human interaction with the universe.

Aside from the Bruno Walter/Otto Klemperer polarity that I discussed in a previous post, there are well over 100 recordings of this eternally attractive work, among them some of the most hopeless, miguided and unlistenable in the entire history of recording. Let me swiftly dispose of the worst by eliminating Arturo Toscanini and Herbert von Karajan, the first for a heavyhandedness not untypical of his general approach to Beethoven, and the second for ignoring Beethoven’s instruction of ‘feeling, not painting’ and splashing out a picture-postcard countryside replete with jolly maids and millers and lowing cattle – at least in the 1963 recording that appeared in his seminal Berlin Philharmonic set. Karajan re-recorded the symphony several times more without ever showing that he had learned much from this original sin. There are moments in the 1963 release when you just want to clap hands over your ears. Unless, of course, you just love crackpot recordings, in which case Willem Mengelberg and the Concertgebouw (1940), with tempi as slack as an old lady’s stockings, could be the right fit for you.

On a higher plane Toscanini’s La Scala successor Victor de Sabata (19747) breathes so deep at first of the country air that you fear he might asphyxiate. But he captures, both in expression and pacing, Beethoven’s idea of feeling – an impression of nature, rather than cowpats. And who knew the orchestra of Santa Cecilia played this beautifully in post-War Rome?

Wilhelm Furtwängler in March 1944, in the thick of world war and genocide, imbues an uncomfortable Berlin performance with intimations of an imminent reckoning. Disturbing as this is, it is outdone in spookiness by a May 1954 Berlin recording, months before his death, the shadows gathering around him. Even the joyous passages of relief after the storm are somehow mournful.

The young Lorin Maazel, conducting the orchestra of the American-funded Berlin radio station in 1960, offers a reminder of what a brilliant artist he was at his best – the sharpest stick technique, the clearest in conveying to players and audience exactly what he understood the meaning of a symphony. Although Maazel went on to head the Vienna Opera, the Bavarian radio orchestra, the Philharmonia, Cleveland and the New York Philharmonic, the recording of his early days in Berlin have an inexhaustible vitality and warmth. Likewise, the over-recorded and not over-intelligent Karl Böhm had one of his finest moments with a 1971 Pastoral with the Vienna Philharmonic, both conductor and orchestra revelling in a common Austrian understanding of their glorious landscape. Just about everything in this performance sings – except, mercifully, the conductor. Brilliant as it is, I am inclined to prefer Erich Kleiber (1953) with the Concertgebouw Orchestra at the top of its form, playing with a delicacy and refinement that surpasses the Viennese. And Kleiber’s pinpoint pacing is incontestable. This is a recording that has been raved over for almost 70 years and still outshines almost all others, before and since.

The Americans on my panel cite George Szell as a supreme interpreter of this work, and they are not wrong. Szell recorded the Pastoral three times, achieving in 1962 with the Cleveland Orchestra an extra-terrestrial transcendence, almost as if they were imagining nature from one of America’s new spacecraft. The strong sound is unsurpassed and I am not sure the finale has ever been more safely landed.

Two more American orchestras enter the fray – the Los Angeles Phil with Carlo-Maria Giulini, bucolic in feeling but with horns blaring the magnificence of mountains. Giulin, raised in the Alpine foothills around Bolzano, had an instinctive affinity with the pastoral expressions of Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler. The other US contender is Chicago in 1974, early in Georg Solti’s rule, when the ranks were packed with recent European refugees who endowed the work with tremulous nostalgia, while the brass blew out windows three blocks away. Of the three Solti Chicago recordings, this remains my first choice.

Among modern accounts, Riccardo Chailly in Leipzig (2012) achieves epic drama in the storm scene and serene consolation in the finale. Simon Rattle is unfailingly persuasive with the silken Vienna Philharmonic (2002), less so with the Berliners (2016). David Zinman (1997) has a marvellous way of combining period practice with a modern orchestra, outfacing even Nikolaus Harnoncourt in this work, let alone the remainder of the period-instrument performers who are disabled in my assessment by striving too hard to make their point. Using a chamber orchestra, as Alexander Rudin (2013) does in Moscow, is no more than a gimmick. The strings-brass balance gets shot to pieces. You won’t want to hear it twice.

The one recording among these many marvellous contenders that I would not wish to live without is both the most romantic and the least predictable: the Abbey Road performance that Klaus Tennstedt gave with the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1986. A refugee from East Germany where he had languished in total obscurity, Tennstedt could never fully believe that he was worthy to conduct the world’s great orchestra. His humility drew performances of surreal fervour from hard-bitten players. The Pastoral Symphony, he told me once, was his favourite Beethoven because he would never fully understand it. Each performance was an attempt at the unattainable. Here one has a sense – a ‘feeling’, Beethoven would call it – of a lone explorer on the steep slope of a mountain meadow, alone amid the marvels of nature. Go straight to the scene by the brook and you will hear an unparalleled childlike wonder at the joy of being alive. The playing is world class and the tension rivetting.