Does the ultimate Fidelio still hold sway?

mainWelcome to the 43rd work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Fidelio, opus 72 (continued from yesterday)

At the start of 1961, Otto Klemperer arrived in London to make his debut at Covent Garden at the age of 75. After a turbulent life, marred by periods of manic-depression and prolonged exile, poverty and ill-health, Klemperer was coming to be reocgnised as one of the last great masters. He had formed a productive relationship with the Philharmonia Orchestra in London and Water Legge had signed him to an extensive EMI contract that encompassed many of his performances. Covent Garden, too, came calling. Its general manager David Webster asked if Klemperer would care to revisit one of his life’s largest milestones.

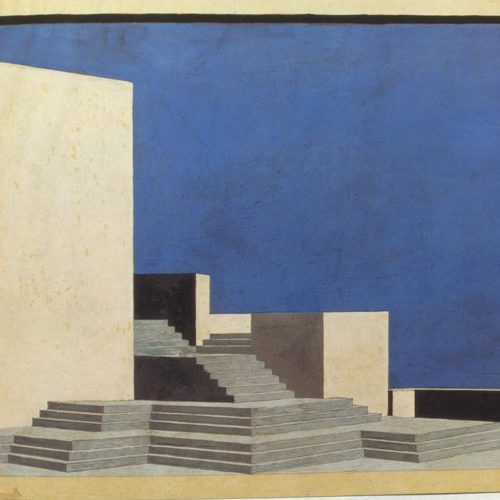

Back in 1927, Klemperer had taken charge of Berlin’s new Kroll Opera with the intention of turning the company into an incubator of modern music, art and design. His opening production, Fidelio, had sets by Ewald Dülberg arranged in cubist blocks which served as a model for contemporary opera production. Conservatives were horrified and Klemperer himself wondered if they had not gone too far. His arch-rival Bruno Walter responded four months later with an opportunistic Fidelio in traditional mode at the Charlottenburg opera house. It was all part of the ferment of Weimar-era Berlin, arguably the liveliest arts scene of all time.

Three years later, the Kroll was shut down. In 1933, Klemperer was hounded into exile and Düllberg died, tragically young, at 45. Their experiment, shortlived as it was, survived as legend. Now, more than 40 years later, Klemperer was being asked to conduct Fidelio, never a box-office draw, in the ambitious though delapidated setting of the Royal Opera House. His daughter Lotte wrote: ‘I almost had to crawl on all fours to get into the orchestral pit.’

Klemperer presided at piano rehearsals with a cast led by Sena Jurinac as Leonore and the Canadian tenor Jon Vickers as Florestan. The old man had not conducted an opera for 11 years and needed time to adjust. Legge reported to his EMI bosses that the entire run had sold out within 24 hours. On the opening night, February 24, 1961, the manipulative Legge visited Klemperer in the interval to tell him that the ‘public is stone-cold’. The reviews next morning were ecstatic. Almost 60 years later, a writer in the Times could remember ‘every detail’.

For the recording, a year later, Legge proposed replacing the entire cast except for Vickers and Gottlob Frick (who sang Rocco). Klemperer stuck by his singers. In the end, for various reasons, Jurinac made way for Christa Ludwig and the Bavarian Ingeborg Hallstein was brought in as a last minute Marzelline. Their voices in the first-act trio with Frick are marvellously fresh, every note nailed and the balance perfectly poised. You need hardly listen to more to know that the conductor is guiding every nuance. In the second act, the former truck-driver Vickers sings like a heavenly cherub.

The recording was made at Kingsway Hall with the Philharmonia Orchestra and chorus in place of unavailable Covent Garden forces. The set has been regarded ever since as the last word in Fidelio, one of the greatest recorded operas. Is that justified? On most counts, absolutely. Klemperer’s tempi are taut and organic, suited to the singing voice while maintaining a high wire of dramatic tension. The concluding sextet of voices is a miracle of human engineering. Nothing jars. The verdict of critics over more than half a century is upheld by consensus.

And yet.

In 2004, a small UK label called Testament secured the rights to release the actual Covent Garden performance of February 24, 1961, with Vickers, Jurinac and the Australian Elsie Morison, who soon gave up singing after marrying the conductor Rafael Kubelik. Both women have greater immediacy than their EMI replacements. Vickers is phenomenal and Hans Hotter (whom Legge replaced with Ludwig’s husband Walter Berry) is deeply affecting as the fearsome jail chief Pizarro.

There are two caveats. The stage show has screeds of spoken German that were omitted from the EMI set and the pit sound and pit-stage balance are unsatisfactory, with the voices darkly recessed. It’s an inspired performance but the ultimate Fidelio recording remains the studio version of 1962. The Testament tape is not yet available on Idagio. It can, however, be accessed on Youtube and you can compare it, minute by minute on your computer, with the Idagio stream of the EMI recording. Both are indisputably historic. Let us know your conclusions.

Klemperer lived the to great age of 88, dying in Zurich in July 1973. The recordings of his final decade generated equal measures of admiration and controversy as his habitual capriciousness alternated with gathering frailty. The results can be inconsistent. Against a heart-stopping account of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde with Christa Ludwig and Fritz Wunderlich (in which the soloists never met), there is a performance of Mahler’s seventh symphony which is almost wilfully perverse – challenging and infuriating by equal measure.

As a Beethoven conductor, his accounts of the 5th and 7th symphonies (in a complete cycle with the Philharmonia) are magisterial, as is his set of the piano concertos with the young Daniel Barenboim, who revered him ever after. It’s hard to categorise, given his variability, precisely which personal qualities Otto Klemperer brought to Beethoven. But, having known his daughter Lotte quite well, I gained a sense of certain affinities between her father and the composer. Both were gruff, mercurial, often misanthropic (was Beethoven bipolar?). Both had huge heads and were plagued with physical illness. Both believed in something larger than themselves.

There was an empathy between Klemperer and Beethoven. You can appreciate it in these recordings.

Comments