Beethoven was no hero. Was he?

mainWelcome to the 44th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Symphony No 3 ‘Eroica’, opus 55 (1805)

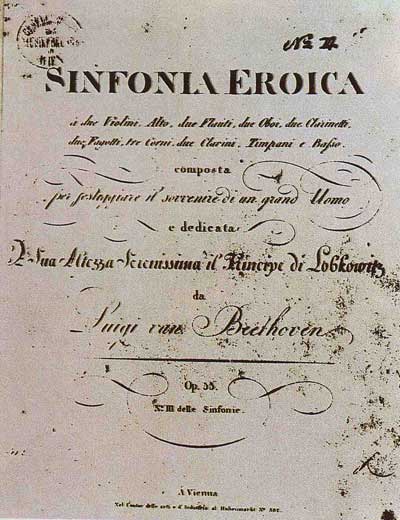

So much nonsense has been spouted about the origins of the Eroica Symphony that we need to get the dedication page out of the way before we can discuss the music. Back to the earliest testimony, Beethoven’s secretary Ferdinand Ries writes that he named the symphony for Napoleon, ‘but Buonaparte when he was First Consul. At that time Beethoven held him in the highest esteem and compared him to the great consuls of Ancient Rome. I, as well as other close friends, saw this symphony on his table, fully scored, with the word “Buonaparte” inscribed at the very top of the title-page and “Luigi van Beethoven” at the very bottom.’

Ries says he felt obliged to tell Beethoven that Buonaparte had declared himself Emperor, at which the composer cried, ‘a tyrant!’ Seizing the top of the title-page, he tore it in half and threw it on the floor. ‘The first page was rewritten and … the Symphony entitled Sinfonia eroica.’

The first edition reads ‘Sinfonia Eroica … composta per festeggiare il sovvenire di un grande Uomo (composed to celebrate the memory of a great man)’. Who was the great man? Could it have been the memory of Napoleon before he became a megalomaniac? Beethoven never explained. What we do know is that he received a fee for the work from an Austrian nobleman, Prince Lobkowitz, whom he could not afford to offend by mentioning a French conqueror. In changing the title, he fudged the issue. Yet it is this symphony, more than any other until the Ninth, that earned Beethoven his reputation as a romantic hero, a rebel against autocracy.

The symphony makes a martial opening statement, dissolves into a funereal second movement, quickens into a nervous scherzo and reverts to a heroic finale in which the main theme is plucked provocatively on strings. That finale theme is taken from a frivolous ballet. Beethoven is playing games with our minds, tossing out ambiguities, appealing in different ways to hearts and minds. At around 50 minutes, the symphony is daringly long, twice as long as any of Haydn’s or Mozart’s. The first performance, on April 7, 1805, at the Theater an der Wien, was received with mixed admiration and irritation. Several reviewers advised Beethoven to shorten it before the next concert.

In its recorded history, two lines are drawn in the sand – the heroic attitude, exemplified by Felix Weingartner (1936) Toscanini (1939) and others of that troubled era – and the ambivalent, most compellingly evoked in December 1944 by Wilhelm Furtwängler in Vienna, an account in which the conductor is determined not to be pinned down which side he is on. No maestro so vividly captured time and place as the wispy Furtwängler, a sensistised human barometer on two stick-like legs. His funeral movement sounds like an irreligious requiem for the whole of civilisation. Recording the symphony again eight years later in Berlin, at even more sombre tempo, he draws shafts of light and hope. Whatever Furtwängler was feeling at the time, that’s what we hear.

I am completely gripped by Oskar Fried’s 1924 recording from Berlin, starting with what sounds like a firing squad and proceeding to embrace all of Beethoven’s shifting shadows, most notably at the opening of the finale. Fried was one of Gustav Mahler’s proteges, the first to conduct the Resurrection Symphony under his guidance; there is something of Mahler in his structural security and emotional finesse. By contrast, another Mahler acquaintance, the composer Hans Pfitzner, is horribly over-explicit in his 1929 Berlin recording of the opening movement. Curiosity seekers will find more to enjoy in a courteous performance by King Frederick IX of Denmark, a capable musician by all accounts, with a very safe hand on the baton.

The music director of La Scala, Victor de Sabata, came to London in 1946 to make a Decca recording with the London Philharmonic Orchestra. His approach to the opening movement of the Eroica is so much gentler than Toscanini’s that you rub your ears in amazement that these two share the same culture and language. De Sabata’s is a highly agreeable account, so agreeable it errs on the side of neutrality.

Hermann Abendroth – Leipzig, 1949 – is magnetic in the funeral movement. One of the most skilled batons of his time, Abendroth whitewashed his Nazi past by becoming a member of the East German state assembly and a cultural ambassador for the oppressive regime. He died a national hero in 1956, unappreciated abroad.

Erich Kleiber with the Concertgebouw in 1950 is indispensable, and I don’t use that word of many recordings. If you need to teach someone how to conduct the Eroica, start here. At no time in a brisk 45 minutes do you think the symphony could be played any other way.

No less definitive are Ferenc Fricsay (Berlin, 1961), with the most finely tuned Scherzo movement of all, and Otto Klemperer (Vienna, 1963), a crusty old master who belies his image to deliver a reading of true tenderness.

No less deceptive is George Szell in Cleveland (1957), where, after a peremptory opening, the conductor allows himself to linger, Karajan-like, on transient beauties without disrupting the flow. Szell used disciplinarian methods to create a great orchestra in a smokestack city. An insecure man, he fretted over poor record sales and expected to get fired any day by CBS Records, which also had Bernstein on its books. Bernstein’s Eroica is one of his most inspired recordings, but Szell here gives a masterclass, fault-free and foolproof.

The period instrument movement of the 1980s brought a welter of alternatives, among whom Frans Brüggen and Roger Norrington shoot to the top of the pile with readings of unflashy integrity – unlike John Eliot Gardiner who just can’t get out of the Eroica fast enough. Nikolaus Harnoncourt, with a slimline Chamber Orchestra of Europe, conjures up the small confines of his noble family’s Viennese ballroom. Even more intimate is Maxim Emelyanychev and the Soloists of Nizhny Novgorod, performing in 2018 as if for a few friends in a railway station waiting room.

Among 21st century takes, Claudio Abbado, Simon Rattle, Philippe Jordan and Manfred Honeck deliver enjoyable performances that fall just short of commanding. The conductor who arrests my attention is Riccardo Chailly with Gewandhausorchester Leipzig in 2011, extremely fast at 43 minutes and combining Toscanini whiplash with the memorial solemnity of Szell and Fricsay in orchestral sound of maximal clarity.

If I could only have three Eroicas, I’d pick Furtwängler, Szell and Chailly, with Emelyanchev a very close contender. None is remotely heroic.

Comments