Barry Tuckwell: His funeral eulogy

mainThese are the words spoken at Barry funeral yesterday by his loving nephew, Michael Shmith. They are followed by one of the recordings of which Barry was proudest – his duos with George Shearing.

Eulogy for Barry Emmanuel Tuckwell

5th March 1931-16th January 2020

The Good Shepherd Chapel, Abbotsford. 30th January 2020.

Uncle Barry. Where to start?

Let’s go back to my own childhood.

I knew his music long before I knew him.

My growing up in Melbourne was encouraged and sustained by two uncles. One was my father’s brother, Uncle Clive, an ebullient, dashing presence in blazer and cravat, who taught me to drive and introduced me to gin. The other was my mother’s brother, Barry, a far more spectral presence, who lived in England and played the French horn. It was Barry who, at a distance, introduced me to the music that would determine the course of my life.

I like to think, somewhat fancifully, that, when I was an infant, Barry probably dandled me on his knee, perhaps positioning me in the same deftly acrobatic way he held his horn.

But my first proper, more lasting, meeting did not happen until 1966, when I was sixteen, and Barry came to Melbourne with the London Symphony Orchestra. He played a Mozart concerto. It was in the Melbourne Town Hall – always rated by Barry as one of the finest concert venues in the world – and I can still sense the horn sound emerging almost as if from nowhere and everywhere at once.

I already knew the work. Intimately. Every bar of it lodged deep into my memory. This was thanks to my mother who, when I was nine or ten, mailed me from London a Decca long-playing record of Barry playing the Mozart concertos. This proved a powerfully effective diversion from the original Broadway cast LP of My Fair Lady.

Some years later, my father bought home his latest LP purchase. It was another Decca recording, of the Britten Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings (we’ve just heard Barry play the Prologue). This recording, too, sank deep into my memory.

Speaking of sinking, I recall Barry’s story of how he once played the Serenade’s offstage solo epilogue from inside a goods lift, facing the back wall – the perfect, evocatively distant, acoustic, he reckoned. Alas, he did not expect the lift to start moving. It began its slow descent at the very moment he began to play: the lower the lift got, the louder he had to play. Fortunately, no one noticed.

Over the years, many other Tuckwell recordings would give me further insight and incomparable joy. But the man himself – the person breathing life into those notes – still remained intriguingly elusive. Who was he?

To say that it took me many years to get to know Uncle Barry is in no way pejorative. It was just that during his performing years he was never in the one place for very long. For him, jetlag always failed to have a starting point. Even when I lived in London in the 1970s, contact with Barry tended to be sporadic rather than regular. But always memorable.

It was only later, after I moved back to Melbourne in the early 1980s, that Barry began to enter my life in a more regular way that would last for almost forty years – especially in later years, after Barry returned to Melbourne to live.

I also got to know some of his long-time colleagues – in particular his brilliant compatriots, violinist Brenton Langbein and pianist Maureen Jones. They comprised the Tuckwell Langbein Jones Trio, which performed for many years all over the world until Brenton’s death in 1993.

Maureen was, and still is, referred to by some as Mrs Lewis. This is easily explained. At the 1988 Adelaide Festival, a caption on a photo accompanying an article on the trio inexplicably read: Adelaide-born virtuoso Brenton Langbein and Melbourne-born horn player, Barry Tuckwell, with Mrs Lewis.

The trio customarily finished their recitals with an quirky encore: Percy Grainger’s liltingly witty Zanzibar Boat Song, scored for six hands, one piano. They squeezed-in along the piano stool: Maureen, flanked by Brenton and Barry, giggling among themselves, as if they were the naughtiest three children in elementary class.

Nicknames, à la Mrs Lewis, and other linguistic trickeries were embedded in Barry’s psyche. He loved them, and most were affectionately bestowed.

(In fact, to be timely, the word ‘eulogy’ was never pronounced that way. Thanks to the minister who officiated at Barry’s father’s funeral some thirty-five years ago and pronounced the word ‘yoo-ology’, family style quickly followed suit. And, we thought, how felicitously ‘yoo-ology’ rhymed with ‘zoology’. Or ‘zoology’.)

Another example – and I can’t recall which of us started this – any reference to Barry’s elder sibling, my mother, was to ‘Nin’s aunt’: Nin being in itself a nickname, of Barry’s daughter, Jane. ‘Nin’s aunt’ (to my knowledge, never used within my mother’s hearing) was merely the theme for a host of elaborate variations. It was a sort of game in which mention of every relative was filtered through this particular prism, the more obscure the reference, the more effective the confusion. Thus ‘Nin’s aunt’s elder son’s daughter’s first son’ (my grandson, Wolfgang). Or ‘Nin’s aunt’s first husband’s first wife’s brother’ (Barry himself – although this took much working out). And so on.

In 1994, Barry received an honorary doctorate of music from the University of Sydney. I recall his speech, addressed more to the students present than anyone more learned, in which he so beautifully described those rare moments in musical performance when you listen with new ears and your world changes. For Barry, such a moment was when he heard the great Mstislav Rostropovich’s first entry in the Dvořák cello concerto. Barry’s message that day was simple: never stop listening.

And we haven’t. Especially to him. Two weeks ago, while I was at Barry’s bedside for what was sadly the final time, I sent my daughter, Poppy, a text. She replied: ‘Please tell him I love him and that I will always play his music to my sons, just as I grew up hearing it.’

I did tell Barry, and is it too much to hope that he heard me?

Although Barry has now gone, his music will never, and can never, die. It remains as fresh and as vital and as persuasive with each hearing. I’ve heard much of it over the past two weeks, and, as with all great art, there is always something – a particular phrase or inflexion – you failed to notice last time.

In writing this, I have been listening to the live recording of the English National Opera’s incomparable production of Wagner’s music drama, Siegfried, made at the London Coliseum in 1973.

One of the precious few instrumental solos in The Ring is Siegfried’s Horn Call in Act II. It is a pivotal point of the opera, indicating the transition between Siegfried’s own youthful impetuosity and his swiftly acquired maturity (he is about to kill a dragon, after all). This brief but treacherous passage is the sole responsibility of the player, who, while respecting the composer’s markings, must maintain his own virtuosity. Barry’s magnificently heroic performance achieved just that balance. How lucky I was to experience it in situ. That was forty-seven years ago. I assure you it is just as compelling today.

Bless you, my dearest Uncle Barry. And thank you for everything.

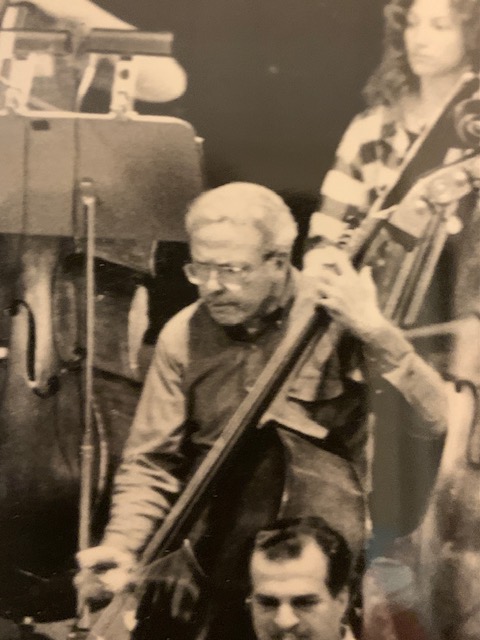

Barry with his sister Patricia, Countess of Harewood, and her son, Michael Shmith, April 2017

Comments