A Beethoven a Day: Keep it quiet, will you?

mainWelcome to the ninth work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

Piano concerto number 4 in G major opus 58 (1805-6)

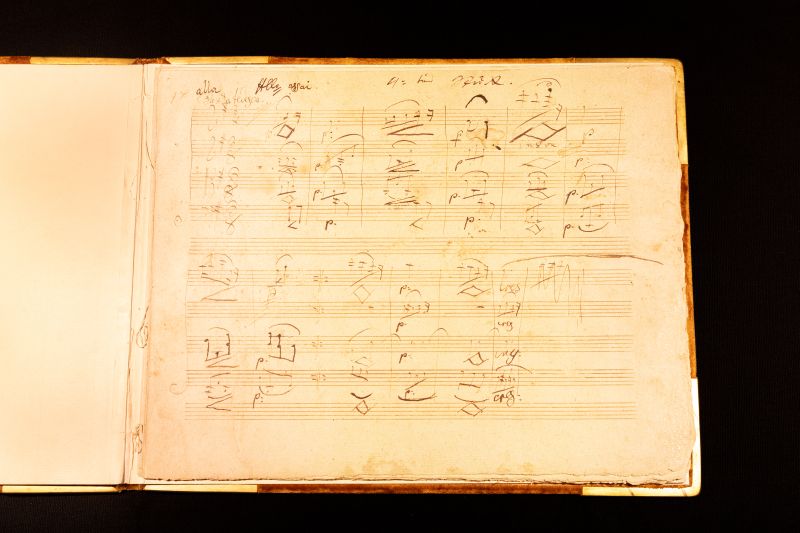

Composed at the high noon of the composer’s creative life, the G-major has the most hushed opening of any concerto, so quiet that the pianist is hardly meant to make a sound. Before this work existed, a concerto would start with a sprightly orchestral introduction with the soloist joining in only when the band ran out of steam. With his 4th piano concerto, Beethoven changed the rules. Not only does the soloist begin, when the orchestra comes in, it does so in a different key, B major. For a few moments, it is as if there has been some mistake and soloist and orchestra are playing off different heets. In the central movement there is further dysfunction, the conductor setting a tempo, which the pianist, after a prolonged consideration, ignores in favour of an ultra-slow solo. The whole work hovers on the edge of chaos.

The concerto was first performed at the palatial home of one of Beethoven’s funders in March 1807, together with the premiere of the fourth symphony. Its first public performance, on December 22, 1808, was one of the longest concerts on record, encompassing aside from the concerto, the premieres of the fifth and sixth symphonies and the Choral Fantasia. In rehearsal, Beethoven had a falling out with some of the musicians, who messed around during the concert. The premiere of the G major piano concerto was the composer’s last appearance as a soloist with orchestra.

Among the 103 recordings listed on Idagio, I begin with Arthur Schnabel, the pioneer of Beethoven on record. Witty, determined and prolific, he pursued a vision of Beethoven that did not necessarily depend on hitting all the right notes. Of Schnabel’s four recordings, the one with Malcolm Sargent and the London Philharmonic had the biggest sales, though my preference is for his 1942 reading with Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra where Schnabel seems to be in a state of transcendence in the slow movement, transfixing the deep-backdrop musicians with his inspiration. Other Germans – Wilhelm Backhaus, Walter Gieseking, Elly Ney, Conrad Hansen, Wilhelm Kempff – sound impossibly literal by comparison. Edwin Fischer, conducted by Furtwängler in 1954, has incedible fantasy in the slow movement. Friedrich Gulda is unusually restrained.

Van Cliburn never really takes off (Chicago, Fritz Reiner, 1963) and Glenn Gould never really settles down (Bernstein, NY Phil, 1961 and 1969). Artur Rubinstein, who can be as frisky as Schnabel on hot coals, takes a measured view of this concerto, evidently a personal favourite. Of Rubi’s four recordings – with Beecham 1947, Krips 1956, Leinsdorf 1964 and Barenboim 1976 – the last is as much a masterclass as a performance, with the old master teaching the young Daniel Barenboim to let the piano lead the baton in tempo and dynamics, just as Beethoven intended. Barenboim went on to record the concerto twice at the piano, an exhilarating 1968 reading with Otto Klemperer and a more subdued account, led from the keyboard with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1987.

The Chilean Claudio Arrau recorded this concerto six times: few achieve anything like his finesse in the finale (Haitink, Concertgebouw, 1964). Of five recordings by Emil Gilels, I prefer the 1957 take with Leopold Ludwig in London to his 1966 retake with George Szell in Cleveland but that could just be personal taste; both are perfectly poised.

In Britain, a pianist known just as ‘Solomon’ came on to the 1950s scene as the last word in Beethoven – until a stroke cut off his career in its prime. Solomon Cutner’s G major concerto, with the Philharmonia and André Cluytens, a masterpiece of understatement, is a milestone in the history of recording. Alfred Brendel, who recorded the concerto four times, can be heard at his most unadorned in the 1959 Vienna session with Heinz Wallberg and an orchestra that dares not speak its name. Many Americans swear by Rudolf Serkin and Leon Fleisher. Both are captivating artists, let down by boxy orchestral sound.

Of the period instrument recordings that I have heard, none is worth a second listen. Nor is the global ambassador Lang Lang who botches his opening bars (with Eschenbach and the Orchestre de Paris), coming in too heavily and distorting the dialogue. He is not alone in this: Van Cliburn, with Fritz Reiner and Chicago, 1963, is equally lop-sided.

In a live performance, Lang Lang’s is the ugliest performance I have ever heard – In Philadelphia, with Eschenbach, 2011, nothing quieter than mezzo-forte.

So, six final choices:

Schnabel 1942, Arrau 1964 and Gilels 1966 are my historic selections.

To these, I would add Vladimir Ashkenazy (Chicago, Solti, 1973) for sumptuous sound and serenity; Stephen Kovacevich (BBC, Colin Davis, 1975) for gravity-defying space between notes and Mitsuko Uchida (RCO, Kurt Sanderling, 1996) for immutable concentration.

If you’re in a hurry, try the super-quick Lars Vogt (Gateshead, 2017).

This work may produce as broad a spectrum of musical opinon as you can find in any musical score.

Some very good comments, Norman, and like you I love Artur Schnabel with Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony in 1942. Unlike any other pianist I’ve heard, on this recording only Schnabel holds his last two chords in the first movement through the orchestra’s and lets them resolnate to thrilling effect after them.

I saw Backhaus play it with Brahms D minor on the same program, Los Angeles Philharmonic and Wallenstein.

Edwin Fischer made two fine versions, one conducting the Philharmonia himself, once live with Jochum and Bavarian Radio, with a spectacular horn clam and false entrance in the rondo. To atone and catch up the horn plays it again,twice as fast. It almost works.

the cadenzas are interesting Clara Schumann, Saint-Saens, Carl Reinecke, Edwin Fischeer, –;nd Beethoven himself. And thanks for mentioning Elly Ney, a marvelous Beethoven player.

Interesting responses. I couldn’t warm to Backhaus.

How could you ignore fantastic Perahia & Haitink ?

Absolutely!

Or Pizarro and Mackerras, and a beautiful Blüthner instead of the ubiquitous Steinway!

Arrau was amazing. So was Gilels. Those two would be hard to beat in anything.

Why keep it quiet? Was the first one too many? ( joke attempt). I can’ t play the fourth albeit haven’t been. I break down like listening to Josef Hassid. The fourth evokes something so personal, like Christopher Robin’s last days with Pooh in the thousand acre woods, only it’s another land. over the bridge.

An very informative summary.

My choice is definitely the Ashkenazy, Chicago, Solti – sumptuous indeed.

I also like Kovecevich, BBC, Davis version.

Another American vote for Fleisher. The sound on the latest incarnation is the best and the playing of all concerned overcomes any limitations.

I meant to add that as everyone knows Leon Fleisher began studying with Schnabel when he was 9. In his autobiography, Fleisher recalled a lesson in which he was playing Beethoven, I don’t recall which piece, and after a few minutes Schnabel suddenly blurted out magnificent. Fleisher stopped playing and said thank you. Schnabel replied not you Beethoven. As he has made clear Fleisher adored Schnabel referring to him as my sainted teacher.

The Obama photo is probably here to provoke some enlightning comments by SueSonataForm…

Now that IS a funny comment! Thank you for that from an English insomniac in British Columbia at 4.30 a.m. A bonny start to Saturday.

Period performances: Jos van Immerseel leading Anima Eterna from the keyboard.

Richard Goode and Ivan Fischer’s recording is one of the greats, IMO

I do not understand the glorification of old recordings with those who have long since died, which are already difficult to tolerate in terms of exposure. For me, two recordings have a reference character ad hoc: Pollini and Abbado with the Berlin Philharmonic and Aimard and Harnoncourt with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe.There is also a wonderful recording with Clara Haskil, if you want to honor the dead posthumously

Does theorchestra really start in B major? I have always analysed the B major chords as the dominant of E minor, which is the relative tonality of G major. Of course due to heavy chromaticisim, the rest of the next 2 bars is tonally uncertain, until the subdominant chord (in C major) returns is safely to G.

Maybe i’m totally wrong….

My introduction to the 4th was an LP of the 1944 broadcast recording of Serkin and Toscanini. Despite the sound quality it crackles (no pun) with excitement and I still enjoy listening to it from time to time. Since then I have listened to many recordings and live performances and it remains my favourite of Beethoven’s piano concerto. My current recorded choice is Bronfman with Zinman and the Zurich Tonhalle orchestra, and I recently heard a very fine live performance by Bronfman and the NACO under John Storgårds.

Fine choices I’m sure, but there are so many excellent ones.

But I was thrown by the photo of Obama-what does he have to do with it?

I don’t think he knows or cares about classical music at all. Who can forget his mangling of Argerich’s name when he was giving an award. That you could understand, but he clearly was reading some notes about her for the first time, and didn’t have the slightest idea who she is-not to mention that sort of music.

Funny how what are described as conservatives are the ones supporting “our” kind of music-something to think about.

Serkin with Ormandy, and Gilels with Ludwig.

Excuse the nitpicking, but Wilhelm Furtwängler was not involved in Edwin Fischer’s 1954 recording (nor was any other conductor).

Schnabel/Sargent, Schnabel/Stock, Fleisher/Szell, Weissenberg/Karajan, and Badura-Skoda/Scherchen.

I think you made the right choices. Arrau 1964 is my favorite.

Arrau – Haitink was always my favorite. A truly wonderful recording!

Carlos Solare correctly posts that Edwin Fischer himself, not Furtwaengler, conducts Fischer’s Philharmonia recording. The two great friends did record Beethoven’s fifth concerto, Brahms’s second, and Furtwaengler’s own together. Furtwaengler’s only commercially released version of Beethoven’s fourth concerto is with Conrad Hansen.

To mention isn’t necessarily to glorify, Karin Becker. It does rsegister long acquaintance with versions that have proved memorable and withstood comparisons and competitionfrom later versions, including Paul Lewis. I didn’t mention Pietro Scarpini, Serkin, Rubinstein, Myra Hess, although I have also enjoyed Kempff and Alexis Weissenberg in the topic work.

Thanks for putting the topic into discussion. There’s a YouTube video performance (probably from the Austrian Radio) by Backhaus and Bohm with the Vienna Symphony. Poker-faced old Central Europeans. Easy to expect dull pedestrian stuff, but it’s not that at all. It’s all wonderful, a step into the heavenly world that Beethoven created in this concerto. Singing, lyrical, intense playing. The orchestra has forgotten that it’s the symphony and thinks it’s the philharmonic. It’s like some of the old recorded performances: you think it’s compressed because of playing time of sides, sessions lengths, whatever, but the performance blazes through. Here there’s no constraint of time but it still seems compressed – until you listen and it’s clear that you’re looking through to a giant and heavenly other world.

Yes, a marvelous performance by two old pros. Great camera shots of Bachaus near the end of his career. While everybody is all dressed up, there is no audience and it looks to be recorded in a studio rather than a concert hall. DG released this as a DVD disc a number of years ago and added a performance of the Brahms second symphony with Bohm and I believe the VPO, if memory serves.

Another aspect of this: can’t imagine the word Kempff and dull in conjunction with each other. They are like same poles of a magnet. Kempff was was a deeply sensitive artist who befriended every dynamic marking and understood every agogic indication. Crescendos and decrescendos were deeply important to him. The idea that a Beethoven performance by him could be dull (at least to someone who actually listens closely) seems odd to me. A Kempff performance is like an ecosystem. There’s a lot going on and it’s happening on many levels.

Moravec/Turnovsky

Stephen Chakwin’s comments on Boehm, Backhaus, and especially Kempff are full of warmth and insight, well-expressed. Kempff’s Brahms intermezzi, Bach transcriptions, and even Liszt concertos the grandest since Emil von Sauer’s with Weingartner, delight those who know his Beethoven sonatas and concertos.

Bbackhaus also, for instance his “Naila” walts Delibes-Dohnanyi transcription, third “Liebestraeume”, Haydn sonatas or Beethoven’s 13th in E-flat, the other Beethoven sonata that is almost a fantasia.

I saw Kempff and Backhaus just one time each, but know their recordings. Even at a technical level, Backhaus’s octave trills synchronized and impressed in the primo of Brahms’s first concerto, and Kempff’s Liszt and Beethoven Op. 109 in a small hall in Wiesbaden were overwhelming.

Claudio Arrau is mentioned. I’ve admired his Beethoven, especially his early records of the Op. 34 and 35 Variations in F and E-flat Eroica. I remember seeing him play the fourth concerto in the 1985-2986 season with Blomstedt and the San Francisco Sympphony visiting Chicago’s Orchestra Hall. It was too late. Arrau didn’t miss notes but was struggling and looked sad on his bench. I also meant to mention Robert Levin playing and improvising his own cadenzas in all Beethoven’s and many Mozart concertos.

“If you’re in a hurry, try the super-quick Lars Vogt.” Yes, indeed. That is the way to listen to Beethoven’s fourth concerto. Did Vogt cut out all the boring bits as well? Icing on the cake if he did. Donald Francis Tovey never wrote analyses of Beethoven’s work as penetrating as those of Norman Lebrecht.

Try Rudolf Serkin’s performance in memorial tribute to the recently deceased Pablo Casals live at the Marboro Festival, Vermont July 1974 with Alexander Scheider conducting. The orchestra was full of individual talent including Kim Kashkashian on viola, Pina Carmirelli leading and Peter Wiley on ‘cello. Live performances give soul which has to be better than perfection.