A Beethoven a Day: At last, some fourplay

mainWelcome to the 13th work in the Slipped Disc/Idagio Beethoven Edition

String quartets opus 18/1-6

A new century had just begun when Beethoven made his first utterances in the format that Haydn invented. It is almost as if he waited until the 19th century had dawned and he was 30 years old, knowing he could do something so different that it would never be mistaken for the work of any other composer, or of the classical past. The six quartets that make up his first set were written for his friend, the violinist Karl Amenda, whose employer Prince Lobkowitz could afford to pay for them.

The bold opening statement of the first quartet, played by all four instruments together together and without harmony, is a clear breach with the ingratiating intros of Haydn and Mozart. Beethoven is saying ‘listen up’, and we do. Each instrument then has its own riff on the composer’s statement. It sounds almost like free speech, which cannot have been lost on the Prince and his household in the fragile social atmosphere of 1800.

The slow movement of the first quartet makes reference to the vault scene in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Once again, Beethoven is staking his ground as a composer who covers the whole of civilisation. The music is rapturous, and it never looks back. Across six quartets, it just grows and grows (although the finale contains a self-quote from Beethoven’s string trio, opus 9).

In my listening, I have tended to rule out ensembles like the Amadeus Quartet who like to root Beethoven in the classical past and veer more towards those who see him as sui generis. Adolf Busch and members of his family, recorded at Abbey Road in 1933, are overwhelmingly convincing in the first quartet.

The Vienna concertmaster Walter Barylli and his 1953 quartet are exhilarating in the last.

Betwixt and between, there is an abundance of choice. The Budapest String Quartet (1952) and the Fine Arts (1966) display a breezy can-do attitude towards the set which is engrossing as you listen, less enduring when it’s over.

The Guarneri and the Emerson extend this attitude into something of an American Beethoven tradition, and no worse for that.

Many swear by Peter Oundjian and the Tokyo Quartet in the gripping Malinconia of the closing quartet, a clear anticipation of the next period in Beethoven’s life, the Eroica years.

The Alban Berg Quartet are so accomplished they make you forget how difficult these quartets are to play, let alone play well. For a more human, introspective touch, go to the Belcea Quartet.

My pal Tim Page writes: I’m very fond of the Yale Quartet set of the late Quartets. It came out on Vanguard some 50 years ago and has something of a cult about it. It makes palpable sense of the music while never becoming prosaic. I’m also very fond of the Hollywood String Quartet version. For a complete set I might go with the Alban Berg, the EMI recording. The early Budapest give an understanding of why they were so revered in their time. The Capet is wonderful in 132 as I recall.

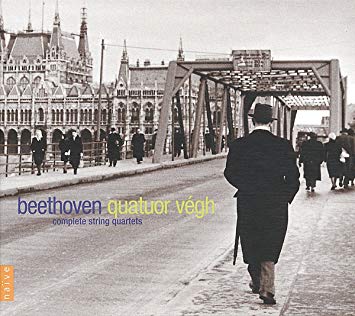

The Israeli psychoanalyst and Haaretz music critic Amir Mandel casts his vote for the Vegh Quartet (with surely the most evocative cover ever to decorate a string set).

The violinist Gidon Kremer opts unexpectedly for the Quartetto Italiano – and you will quickly understand why They play like Pavarotti sings, without any sign of effort.

Such variety out there. Get listening.

Comments