Early music mourns a core publisher

mainWe have been notified of the death of Clifford Bartlett, whose King’s Music publishing company brought to light and edited a host of baroque and early scores for modern-day performers.

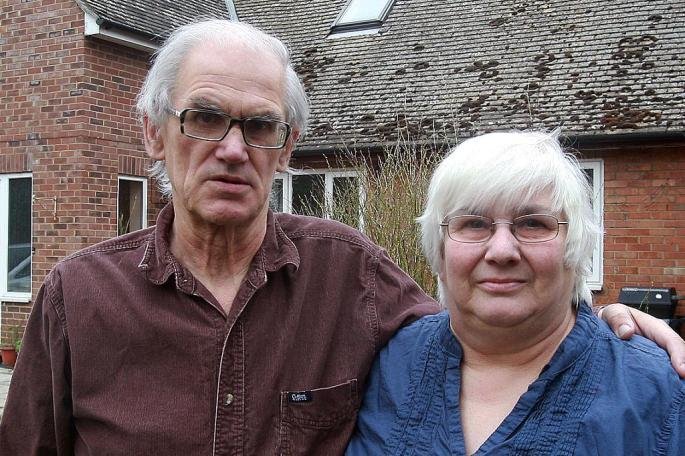

Bartlett, a quiet man with two handicapped adult children, was saved by leading artists from losing his home in 2015 after his business was crashed by fraudsters.

I’m sure all musicians will be saddened to hear of the death of Clifford Bartlett, whose scholarly editions of early music published through his King’s Music company have played such an important role in the development of early music in the UK and further afield pic.twitter.com/bPdo0JFc46

— Brian Robins (@EarlyMusicWorld) August 13, 2019

So sorry to hear of Clifford’s death – condolences to his wife and family. I first knew him when he worked in the BBC music library (1970s?) and and was appalled in due course to hear of his situation at the hands of photocopier fraudsters. He was a splendid fellow and his scholarship was unimpeachable, as his editions of Monteverdi et al. will demonstrate for as long as they are in use. RIP.

He really did make a lot of gorgeous music available for us to hear today.

I’m so very sorry to read this. I once spent a delightful afternoon and evening in his company at an early music festival years ago. A charming, knowledgeable, utterly unpretentious man who will be sorely missed. May he rest in peace. The heavenly choir is richer now.

For decades, Clifford was the “go-to” man for a vast amount of pre-1750 music. Not only did he publish well-priced editions of many hundreds of works, but he was a walking musical encyclopaedia. No matter how obscure the composer or the work, Clifford knew of it, and knew where to find it. He gave his time and unique scholarship with unfailing and considerable generosity. For decades, the shelves of every period instrument musician anywhere in the world could be guaranteed to be well stocked with Clifford’s editions. Equally, Clifford’s phone and email was usually the first port of call when a weird and wonderful work needed printed material.

A visit to Clifford’s home was quite an experience. Not just because of the demanding presence of his two severely handicapped children (who have survived well into adulthood, still requiring significant and constant attention); not just because you could not comprehend how much printed music could be stored in one house; but, most memorably, because when he dived off to find a piece of music you realised that his filing systems were extraordinary. In what to many of us would appear to be wild chaos, with innumerable piles of music stored in apparent random heaps, more piles, and further heaps, Clifford knew where to find that single sheet of trombone 3 or viola 4. The fact that it was probably stored under something completely different baffled most of us, but Clifford’s mind worked in a different way. That unique mind hugely benefited the world of “early” music. At exhibitions around the world, Clifford’s stall was always busy, with dozens of friends and colleagues from every corner of the globe, and from every walk of musical life, affectionately greeting him.

When this thoroughly decent man was horribly scammed by two unscrupulous photocopier salesmen piling a series of unaffordable leases onto him – to the extent that Clifford and Elaine were in serious danger of losing not just their life’s work but even their house – it was a token of the esteem and affection in which the music business held him that a very substantial sum of money was raised. Every notable musician from the “early” world, alongside hundreds of professionals and amateurs, did their bit to contribute. Nonetheless, the toll on Clifford and Elaine from that awful blow was significant.

With Clifford’s death (a few days after being moved into a nursing home, and thence rushed into hospital suffering from sepsis), pre-1750 music has lost not just one of its real characters, but a modest and unassuming scholar whose life’s work greatly benefited almost every performer, professional or amateur.

Thank you so much, Clifford. Requiescat in pace.

Very sad indeed to learn of Clifford’s passing; I also first met him when he was BBC music librarian, and he arranged for me to borrow Roger Fiske’s edition of the (then little-known) ‘Dragon of Wantley’ for an undergraduate performance in 1983. Saw him frequently thereafter at conferences, etc., but not so much in recent years. A lovely man with a gentle sense of humour and, of course, huge fund of knowledge. Condolences to his family.

Not alleged fraudsters, but convicted, as was the evil solicitor who tried to con the children out of their home. It would have been Clifford’s 80th birthday today. I am remembering him and admiring the surprising number of his excellent editions acquired over the years – many studied at length, others at extremely short notice! You could always rely on him.

A year on, I am remembering again the uniquely valuable presence and contribution of Clifford. How unfailingly kind, friendly, inspiring and helpful he was, and how brilliant. People like that restore faith.