Bernard Haitink: I owe it to the boys who never came back

mainThe Chicago Symphony violist Max Raimi has allowed us to publish this recollection of a remarkable conversation with the great conductor, whose retirement was announced this week.

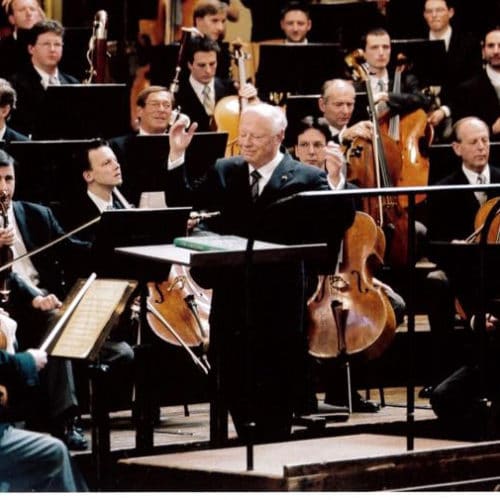

Bernard Haitink announced his retirement today; he will conduct his last performance at the end of this summer. I am extremely grateful to have worked quite a bit with him; he was the CSO’s Principal Conductor between the tenures of Barenboim and Muti.

Here are some observations about one of my all time favorite conductors:

Because his technique was so unfussy and drew so little attention to itself, it was almost universally underestimated. With a minimum of motion, he could give you every single particle of information you needed. I always could play with confidence and freedom under his baton. I read once that he admonished student conductors, saying “Don’t distract the musicians–they are very busy!”

No matter how familiar he was with the music he was performing, he never became jaded. There was not a shred of artifice or mannerism in his interpretations. He let the music stand on its own considerable merits, unlike a number of conductors who seem to grow bored even by the greatest masterpieces and need to artificially inseminate them with eccentric interpretive touches. Maazel and Tilson Thomas are excellent examples of this, at least in my view.

I still treasure the memory of a conversation I once had with Maestro Haitink. On a Chicago Symphony European tour roughly a decade ago, he threw a party for the orchestra at a winery just outside of Vienna. It is relevant to the story to mention that one of the programs featured Shostakovich’s last symphony. I arrived a little late, and it turned out the only seat still available was at the “adult table”, right next to Haitink!

I was nervous; I don’t dine with great conductors very often. So I drank a goodly quantity of wine a bit too quickly. Then I heard myself saying to him, “Maestro, I find it so meaningful that we are playing Shostakovich’s final symphony with you. I think of it as the last of its kind, the last traditionally structured symphony–sonata allegro first movement, slow movement, scherzo, finale–in our repertoire. Just as you are the last of your kind, the last conductor we see who has a living memory of the world our repertoire came from, Europe before Hitler blew it all apart.”

Through my wine haze, I realized that I had basically called our revered host a fossil. But before I could regret it, his eyes lit up and told me stories about his life as a boy in Amsterdam during the Nazi occupation. His father was an electrical engineer, responsible for Amsterdam’s electrical plant. He was pressured by the Dutch resistance to shut the city down, but if he had, he would have had to answer to the Germans. He was in an impossible double bind, and it broke him; Maestro Haitink told me that his father died shortly after the war ended.

Then he said something absolutely extraordinary; the most amazing part of which is that he seemed to believe what he was saying: “You know, I was nothing special back in my school days. There were so many of my peers that were much more talented than I was. But they were all Jewish boys, and they were murdered. I was all that was left–that is why I enjoyed the career I have had.”

Bernard Haitink 1957

Comments