Carter is my blind spot

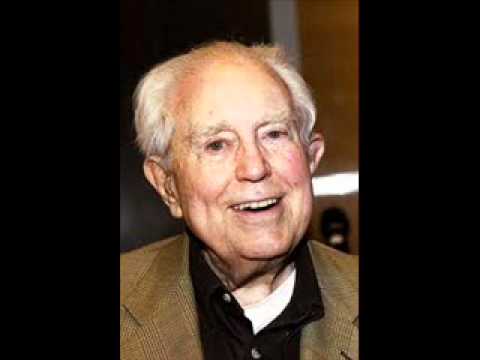

mainI spent an hour once with Elliot Carter, one of the emptiest of my early career.

We talked about Schoenberg and Ives, I remember. He seemed so Boston-bland, so untouched by life’s struggles, so anaemic and passionless, that I barely managed to write up the interview and have never found a key that made his music meaningful for me.

My pal Tim Page betrays a similar ambivalence in his NYRB review of a new book on the composer.

There is a fond belief that we glean otherworldly revelations from the late works of composers. We meditate upon the hymnlike final scores from the dying Beethoven and Schubert, are heartened by the brisk comic affirmations of Falstaff, Verdi’s farewell to opera, and marvel at the serene, luxuriant leave-taking in the Four Last Songs by Richard Strauss.

In the case of Elliott Carter, however, mystical expectations are best set aside, even though he wrote more and later “late” music than anyone. He composed steadily in his own distinctive manner from his teen years until that day in November 2012 when, at the age of 103, he simply stopped…

Read on here.

This article captures the blinkered parochialism of New York’s new music world. Page writes, “I am always surprised by the shimmering grace of Babbitt’s music, by its emancipation from any worldly angst…” Never mind that the city was, and is, crawling alive with grotesque social injustice. So much American musical thought is imprisoned in elite schools that nurture a classist, social indifference — a form of moral crudity posing as artistic refinement. The Hollow Men of the Ivies, as it were. Carter wrote carefully crafted music, but he was an inherent manifestation of this milieu – a kind of safely apolitical avant gardism as prim and proper as it was classist and parochial.

During the 30s and 40s America had socially conscious composers, but after the purges of HUAC and the large-scale, covert manipulation of the arts through the CIA’s Congress for Cultural Freedom, the landscape was permanently altered. No more social questioning during the Red Scare. The composers of abstract, *apolitical* art became the new ideal. A smugly Ivy League, classist sensibility and a scientific bent further enhanced the image. Composers like Barber and Copland were not just pushed aside but shamed for their more approachable work. Copland was even hauled before HUAC. The composer of the most American of American music was so traumatized he was never the same again. It is little wonder that composers like Fredric Rzewski lived abroad.

There were certainly other major factors at work as well, but these reactionary forces were a large part of the change. I think it will be a long time before we have the distance to fully understand what happened to American culture during this period, and how it has affected our political and social landscape. How does one look around at Trumpistan and not sense something went badly wrong with our cultural understanding?

So…you are not a fan, then?

Actually, I am, but not of the milieu of which he was a part.

“composer of the most American of American music”

Support that preposterous old doctrine, please.

The meaning is to be taken in the context of my comments. As a reference, Joseph Horowitz’s “Copland and the Cold War” is a good example.

There is a good summary of Copland’s identity as an American composer and his persecution by HUAC here:

http://news.minnesota.publicradio.org/features/2005/05/03_morelockb_unamerican/

And here is the transcript of Copland’s interrogation by HUAC. It documents Copland’s status at the time as an essential representative of American music (a status that is now iconic.) The transcript also shows how deeply disgusting the American Federal government can be (also a status that still exists…)

https://www.npr.org/programs/atc/features/2003/may/mccarthy/copland.html?t=1554025148880

In the above linked HUAC transcript, the two interrogators of Copland are MaCarthy and Roy Cohn. Cohn later became Donald Trump’s lawyer, personal friend, and mentor.

One you learn that “Fanfare For The Common Man” was inspired by a speech by Stalinist-dupe Henry Wallace, it’s not as much fun to listen to.

He rightly defended himself.

I wish I had Copland’s abilities for such repartee. Truly impressive. He really did have progressive political leanings. John Williams has made an arrangement of a choral section from The Tenderland that reveals something of Copland’s socially oriented thought. (see url, and forgive the video images which are a bit over the top.) Copland showed genuine commitment to the impoverished farmers of the Great Depression. The Tenderland and other works stand in such stark contrast to the apolitical abstraction that so many later composers like Carter embraced. One can only wonder what sort of artistic expression would have evolved if this line of thought had been allowed to continue.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLM_YTnmLto

The arts are NOT tools for social engineering, however understandable in the context of political crises. It is not the political aspects of C’s works which come-in for criticism, but their lack of musical qualities: it is a sophisticated, decorative sound art. Although in his later late works he turned back to early 20C melancholic, claustrophobic expressionism, a watered-dosn Schoenberg.

http://johnborstlap.com/on-the-death-of-elliott-carter/

John,

Carter has written for those who are willing to learn how to understand and follow complex music. The task of the listener is not to reject what seems at first encounter irritatingly “unintelligible,” but rather to stick with the new as if it were a new language, and learn its order and logic and then derive pleasure from it. If emotion and sentiment are communicated by music, they are only accessible after “one understands how the music works”; it is then that one can “perceive the emotion.” All great music demands this kind of time and energy if it is to be understood and loved. What the late music of Elliott Carter suggests is that even the most dense and complex of Carter’s finest works can succeed with the wider audience because his music works on many levels. Because there is so much genuine richness in Carter’s music, it has a real chance for success with the audiences of today and tomorrow.

Perhaps what makes Carter great is that he, through painstaking discipline and concentration, has invented music that works the way the music of the great masters from the Classical era did and that reaches across a wide range of listeners. Carter’s music has, in the end, an emotional necessity behind its existence. It is therefore neither academic nor polemical. Its surface of modernity is not artificial but human in a unique, introspective, dramatic, and elegant manner: what is unexpected and seemingly unintelligible has emerged in an uncompromisingly modern manner akin to Mozart, Haydn, and Chopin, leading listeners to trust what they hear.

Yes, I know those arguments well – they come down to: when you really understand how it works, you will begin to enjoy its qualities. It is an argument stemming from Schoenberg, and it became one of the orthodoxies of modernism: rejection is misunderstanding and conservatism, and if people would take the time and the effort to really try to understand the workings of new music, they would inevitably end-up with enjoying it like the music of the ‘classical masters’. But it is naive to think that there is an inevitability about ‘really understanding the workings’ and then enjoying it. Namely, it is also quite possible to ‘really understand’ the workings and thus understanding why one does not enjoy it at all and why one has to conclude it is something fundamentally different from those classics which are always invoked at such occasions.

There is a difference between music and gestures in sound art which, through their intensity as a gesture, imitate ‘expression’ in music. The complexities of Carter’s works take place in the surface, but the complexities of great composers of the past: Palestrina, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven etc. etc. (etc.) take place in the background, the surface is mostly quite accessible for contemporaries, at least within a relatively short period. It is this confusion between background complexity and foreground complexity, and between imitative gestures and tonal dynamics, which contribute to the misunderstanding that Carter is just like Bach, Mozart, etc. which is entirely nonsensical. Carter wanted something fundamentally different from what the musical tradition had cultivated. And his oeuvre definitely has its qualities, apart from reflecting the confusions and disruptions of modern life, but they are not musical qualities. The narrative of modernism is based upon wrong assumptions, which – by the way – can be easily disentangled.

John,

Botstein’s defense of Elliott Carter is no different from that of Beethoven’s apologists in the first half of the nineteenth century defending the composer from the (very common) accusation that his later works were those of a madman, and a deaf one to boot (e.g., from an article written in 1840: “There is reason to fear that Beethoven suffered the moodiness of his temper to affect the productions of his muse, and was thus induced to fill his music with crude innovations out of a morbid opposition to existing opinion”…..).

In turn, your response to Botstein is no different from Beethoven’s opponents.

So which of you will be proven right, and when?

T

All assessments of contemporary music / art are provisional. But it is intellectually dishonest to take historic disagreements out of its context (given the very different historic context and all the changes that have happened since) and simply project them on a current situation.

All new music in the wake of Schoenberg takes his premises concerning tonality and distribution of the material as a point of departure and it is not difficult to see that S’s ideas about tonality and complexity are wrong. This is not conservatism but understanding of what Schoenberg wanted: he thought that tonality was a mere human construct which could be replaced by another human construct. But tonality – which makes music accessible to the ear and offers the possibility to create an ‘inner space’ in music – is based upon the physical reality of the properties of sound (which had already been discovered by Pythagoras).

John,

But there are plenty of “world musics” that do not use tonality and yet which are still (presumably) accessible to the ears of those that hear them.

That is incorrect: all musics of all cultures are based upon tonality. That is: they make use of the basic proportions like the octave, the fifth, fourth, and where they deviate from tonal orientation points: that is a decorative, expressive means (like in the Arabic ‘maqam’). Also Chinese opera which for Western ears may sound peculiarly ‘wrong note’, uses a tonal orientation. It is the fundament of music, as tonality is a physical property of sound. Old Pythagoras (ca. 570 – ca. 500 BC) has already figured that out. Tonality is not something created, but discovered, like mathematics. It is part of our surrounding reality and our ears and brains are hardwired to perceive it.

The music is synthetic and divorced from nature. We are given nature; why would we want to study and attempt to appreciate and validate the artifice of a synthetic system conjured up by a person?

Indeed. See above.

OMG! Yes, the artistic oppression under Trump! It is simply… not there. (That was not just wrong, it was off-topic.)

Carter bought his way to the top. And by the top, I mean the academic circle-jerk that has done more to alienate intelligent, passionate devotees of the art than any other malign influence.

Only recently, after decades of this onslaught on aesthetics are Art Music appreciators feeling brave enough to say – it’s ugly and we don’t like ugly. We never did.

Speaking of ugly, “circle jerk” is a rather vile metaphor for people who see things differently than you do. I am sure that you yourself have never participated in such things, but still.

The “academic circle-jerk” that Milton Babbitt struggled so mightily to establish. Where composing and performing are concerned, university music departments have been a curse.

Trumpistan?…0h Lord.

Ah! So Elliot Carter is to blame for Trump! Thank you for connecting those dots in such an unforeseen way. Now on to the barricades!

To belabor the obvious, the point is that Trump is a result of decades of social neglect and erosion which also included damage to our cultural lives.

To me, many composers seem unable to comprehend politics in relation to what they do and end up looking foolish; no one seems to call them on their contradictions which is the result of illogical thinking. There are many examples, but one I’ll give is Henze (whose work I admire) who was an avowed Marxist but chose to live and work in democratic/capitalistic countries. To me, ideals don’t mean much unless they are put to the test. On the subject of progressivism in the arts, I am of the opinion that, taken to its limits a post modernist sentiment would rule and individualism would lose out to ideas of what’s considered good for the masses. And Trump is no more the result of social neglect or erosion than any other president.

It’s true that Henze was a Mercedes Marxist, as they say, but I think a closer look reveals that in many ways he lived according to his ideals. He left Germany and lived in Italy where there was much more tolerance for his politics. He attempted to express his ideals through his music. And he devoted a lot of effort to helping young composers. One sensed that his worldview was different than many composers, and very different from the attitudes often found in the educational and social caste system of America’s elitist schools.

Historically, Italy has been a safe place or haven for artists who enjoy armchair-style Marxism; it’s where they can live in a vital arts community, freely create, profit without answering to the State, and BS all they want without anyone calling attention to their inconsistent philosophy. I greatly admire some (not all) of his work, but in the area of politics, he was incapable of thinking logically. I have his biography, and as far as living “close to his ideals”, he did, if you ignore his inane politics.

This is predicated on the view that Marxism only has one definition, but in reality, it is a fluid philosophical concept that is used to define a wide range of governments. Stalinism, Maoism, Social Democracy, Trotskyism, Autonomism, Collectivist anarchism, libertarian socialism, etc. Even Marxist free marketism as seen in China. It is thus difficult to say that Henze didn’t live according to his Marxist ideals when we don’t really know what his ideals were. One also has to ask how he could even live by his ideals in a society that offered little framework for them to be practiced.

The other problem is that criticisms of Marxists not living their ideals is often a specious trope used to undermine the philosophy in general.

Fully aware of all the permutations of socialism, the arts have never fared well under its mantle, and we don’t need to cast out ‘specious tropes to undermine’ it because history has not recorded a rosy picture of working artists in socialist societies. But you’re free to intellectualize it’s supposed ‘benefits.’ With Henze, Tippitt, et al, since they were highly successful, it apparently it didn’t matter to them “how” they could live by their ideals “in a society that offered little framework for them to be practiced.” In other words, the trade off (success over fully embracing Marxism) would have meant the end of their careers.

There does not exist progressivism in the arts. What goes under that name is nonsensical. In the arts, there are developments, up and down, and diversification, and explorations, and returns. But there is no progress.

‘Progressivism’ is a socio-political term, as ‘progress’ is measured by how close an objective comes to embracing Marxist doctrine. And once you understand what Post-modernism is, how it’s influenced public opinion and curricula, you won’t be saying that progressivism doesn’t exist in the arts. Refer to Postmodern Perspectives: issues in contemporary art, H. Risatti.

‘Progress’ or ‘progressivism’ are not terms in the exclusive possession of marxists. There is in 20C thinking across the board a notion that there is, or should be, progress in the sense of: improvement. These are very general terms used in all types of context, greatly varying according to subject. In the arts, there is improvement, but the associations going with the notion of progress are focussed upon the idea that when something is new, newly invented, it must THEREFORE be better than something that does exist already. This idea comes from science, where real progress indeed exists, but in the arts, that is a nonsensical and dangerous notion, because it would mean that Picasso has improved on Velasquez, that Schoenberg is better – because of being much newer – than Bach, while aristic quality is atemporal. The explorative architect Léon Krier said about classical art, in a very general way: ‘Classical art is atemporal like mathematics’. I think that offers much food for thought.

‘Progressivism’ most definitely refers to Marxist thinking whereas ‘progress’ is not owned by any socio-political theory. The term ‘progressivism’ as a socio-political construct has been in use for over 100 years and it’s important to know the distinction. My point is that this socio-political mentality has crept into arts foundations, board rooms and arts administrations, promoting group think approaches to fostering community art over the individual. BUT, your point about so-called ‘progress’ in the arts is well taken. I have wrestled with this for years, the Western idea of progression in the arts. In comparing Bach to Schoenberg (for example), I would prefer to use the term ‘evolution’ or ‘movement’ over ‘progress’ because ‘progress’ infers improved or better, and I don’t think that is what Schoenberg had in mind. I agree that classical art is ‘atemporal’ and that the idea of ‘progress’ can be deceiving.

Bullshite! You are much to full of yourself William. Easy to generalize and hold up scapegoats. It is the stock and trade of social justic e warriors. Get off my lawn!

Decades of erosion and damage to our cultural lives has come from the loony Leftists who have infested academia, the media and the entertainment industry.

He remains, for me, one of those incredibly overhyped composers whose inspiration comes (if at all) only in the tiniest spurts.

History will put him as a footnote lower on the totempole from Auber.

Actually, Auber’s star is on the rise again, surging in the wake of the removal of prejudice against Meyerbeer. But it’s true that musicians love Carter more than the average listener. Of which I assume you are one.

“But it’s true that musicians love Carter more than the average listener.”

This is often claimed, but is it really true? Certainly there are musicians who have be very vocal in their love of Carter. Yet on classical music fora open to modernism one meets plenty of passionate Carter fans that are not professional musicians, and I personally suspect that – even if Carter remains a niche taste – there are more such non-musician fans than musician fans.

One does not have to be a musician or a music lover or a person who understands music, to be interested in, or to enjoy Carter. When I spoke with intelligent, sensitive and cultured people who had a special love for complex modernism, like Carter’s or Boulez’, or even Xenakis’ or Haas’, inevitably psychological neurosis made itself known. Such sound art functions like a rorschach test where the suppressed, secret hatred of your mother-in-law is revealed, so it functions as a tool to make contact with your subconscious emotional turmoil. But what does this say as to the art form?

Plenty of passionate Carter fans? How many? 12 or 15 or 20? Yes, the response on classical music fora is indeed conclusive.

I attended the premiere of his Oboe Concerto in 1988 in the Zurich Tonhalle.

It was sold out, or very nearly so (seating approx. 2,000).

But that is entirely understandable, such works are attractive for the Swiss, they like complicated, useless challenges – think of their knives, and the careful and patient way in which they drill holes in their cheese according to traditional lists for exact number and location for every kind.

I’m sure he was just as excited to lose an hour with you…..

Ha. I actually LOL’d at that one.

Vraiment bien touché, mon cher. After all, it really does take two to tango, doesn’t it?

After, he spoke of little else for days. What he said…well, best let that lay.

==he wrote more and later “late” music than anyone

LOL

I think his key works were in the 70s and 80s

Piano Concerto, Symphony of three orchestras.

There’s a lot of doodling after 2000. All those pieces he churned out for Barenboim, for example

The article has some interesting points (thanks for sharing) like EC’s distaste for sports.

The reason that EC lived so long was that he never took exercise.

My sport activities, extremely limited as they are, have been, and continue to be, a great source of painful suffering to me and of great hilarity to others. Which is why my answer to the question “What is your favorite sport?” is always: Opera.

May I add to that the magnificent Concerto for Orchestra (in my view his real out-and-out masterpiece) , the Double Concerto (admired by Stravinsky), the 1st and 2nd String Quartets, perhaps A Mirror on Which to Dwell and the later, delectable Boston Concerto. I find most of the late music very dry and written without great inner necessity. My problem with his music is its lack of repetition and variation, and its lack of sensuous surface. It can come over as ‘complicated’ rather than ‘complex’. Politically, Carter was liberal – Left and was more admired, and performed in Europe (especially the UK) than in the USA.

“…… and have never found a key that made his music meaningful for me.” Of course not, since a key was the very thing EC tried to avoid in his works on all costs.

I don’t know about the rest of you, but after a hard day at work, I always come home, pour a straight scotch and turn on Elliott Carter.

It makes life’s troubles float away.

Yes that’s my experience as well, I do hear so much classical music in the work place that I’m relieved to have Boulez or Xenakis washing over me, just brilliant surface and no probing in places where I would rather keep my clothes on! I don’t know Carter at all but I’ll look for a CD. Must have been an adorable guy.

Sally

Sorry about that….. she intruded on my computer, because I had forbidden her to listen to Carter in working hours (which considerably increases her typo’s). Some people don’t understand their own rorschach tests.

Thank God Elliott Carter is dead – and so doesn’t have to risk reading some of the above rubbish.

There’s news I’ve been withholding and I may as well spill it here, the presence of elitists and jerks notwithstanding, sometimes I think there are enough interlocking circles of jerks and elitists to make a new Olympic logo! But so what.

The news is that Elliott Carter is not dead, he is alive, and not just as an artistic spirit! He is pale, that’s all, and yes, thinner.

Working alone and in silence below ground, energized by reports of the insults raining down on his memory, he beavers away, eager in some future decade to see the look on the faces of those nay-saying elitists when they lay eyes on the vast piles of manuscript.

Much much much higher than the time before, when he came back from the dead. O the fund-raising, o the memorizing, o the second-guessing by a world that had praised EC as out “greatest living composer” for so so many years!

Who’re the elitists now, eh?

Exactly!

‘During his life, he was immortal.’ Heinrich Heine

Is EC today in a ménage à trois with John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Grace Kelly? Just asking.

BTW, loved the use of “beaver” as a verb!

jm

I once spent an hour with Mr. Carter, too, and he could be a bit prickly. His family fortune meant not having to write music to sustain his livelihood. But he was devoted to his wife, Helen, and his music changed at the end of his life: more open, less complex, more interesting, more lively.

He seemed to have looked back to the early beginnings of modernism with the Viennese Three, when it still was controversial and had a revolutionary spirit about it, there on the cultural barricades of old Vienna, where young artists protested against all that beauty, classicism, ornaments, formality, civility and joye de vivre – all of that had to be cut out of life and the Truth be revealed in screams and dissonance.

Everyone has blind spots. Mine are Brahms, Schumann, Mendelssohn and Sibelius. As to Carter, there is plenty that does nothing for me, but I grew up with the string quartets and love them to this day. You have to give him something for remaining creatively active past age 100.

The composer of the last 50 years that I listen to most often is Ligeti, but that is another tale. I’d rather listen to the music of Carter and Ives than that of Copland or Bernstein. Bernstein’s symphonies are mediocre – better to listen to Piston or Sessions. I’ll stop wandering…

Modernity has its own results and reflections, nothing wrong with it. Whether modernity in itself is a good thing, depends upon context. Carter always reminds me of Time Square at rush hour, Brahms of pristine woods where you smell the tree-bark. But are woods modern?

“He seemed so Boston-bland, so untouched by life’s struggles…”

Maybe that’s how you live to be 103. Just sayin.’

To each their own, I guess. I’m a huge fan of Carter’s music – I think I’ve heard all of it, with a few exceptions – and I know for a fact that there are plenty of people like me around. His music remains quite widely performed, as well.

Yes, it’s like suspenders: it keeps up the modern spirit.

How appropriate that we’ve arrived at an anniversary of this news item:

Posted: Sun Apr 01, 2007 6:53 pm From the Associated Press NEW YORK

American composer Elliott Carter, an exemplar of the atonalist style of modernism and according to admirers the greatest living practitioner of his craft, apologized to music lovers around the world today for what he called “a half century of wasted time.”

“What was I thinking?” the venerable Mr. Carter, 99, said at his home in Manhattan.

“Nobody likes this stuff. Why have I wasted my life?” Carter said he “went wrong” back in the 1940s and spent the next 60 years pursuing the musical dead-end of atonality.

In the past seven decades, he has produced five string quartets, a half dozen song cycles, works for orchestra, solo concertos and innumerable chamber works for various combinations of instruments—all in an advanced, complex style he now dismisses as “noise.” Despite consistent encouragement of many mainstream musicians such as Boston Symphony Music Director James Levine, for Chicago Symphony conductor Daniel Barenboim, and the cellist Yo-Yo Ma, Carter said his many admirers were “delusional.”

“The critics who said they were just congratulating themselves for being smarter than everybody else were right all along,” he said. “We should all go back and get our heads on straight.” Carter said he blamed his late wife, Helen, for turning him into an unrepentant modernist. “She liked this stuff, and I could never say no to her,” he said. Mrs. Carter died in 2003 at age 95. Since then, Carter said, he has been reevaluating his aesthetic.

“I’d like to write something pretty for a change—maybe something based on an Irish folk tune,” he said. He was uncertain whether he would withdraw his substantial catalogue from the repertoire, though one alternative would be to revise his works, ending each with a tonic triad, he said.

“I feel like an enormous weight has been lifted from my shoulders,” Carter said. “From now on, I promise to be good.”

April 1st???

🙂

Hilarious……

I found Carter at his most interesting when we discussed Charles Ives. He confirmed some ideas I had about Ives’s intentions in composing such complex works.

Carter and Ives took off in the same boat, leaving for the open sea of total freedom but never landing on a new, truly artistic continent. They both rejected ages of artistic experience and atemporal discovery, like creating a mathematics without mathematics.

http://johnborstlap.com/why-ives-is-not-a-great-composer/

Norman, thanks for linking this.

Throughout the past 40 years I have purchased at least 12 Carter scores to study, which I enjoyed doing. My main interest was to learn how he managed to notate his poly-tempos and remain within traditional parameters. But I also learned that his large scale poly-rhythms, which structured the pieces, there on the page, were not at all audible in performance. This is was always perplexing to me, and seemed to be a fundamental flaw. Furthermore, like many composers of that era, I found the resulting harmonies meaningless in any aesthetic way, neither interesting nor fascinating, serving only to maintain the total sense of atonality (although occasionally there were references to polytonality). I think Tim Page is absolutely right when he says he finds the astringent works of Copland to be the strongest influences (certainly not in his methods, but in his rhetoric). There is also a kind of neo-classicism that runs through much of Carter’s music, even the music from the 60’s on, poly-rhythmically morphed, of course. For all of the interesting complexities in his music, the music always retained a certain dullness for me, right from the get-go. I respected it while not much caring for it.

A comment from a musically-sensitive listener. How come people, whose ears have developed on music, to find Carter dull? Because in Carter, the notes don’t form meaningful (musically meaningful) relationships, which makes a meaningful structure and narrative possible. But this is something different from lacking audible structural articulation points: there are lots of structurally important moments in classical music which are inaudible. Just 2 examples; in one of Bach’s Duets, there is a point in the middle from which the music unfolds in exact retrograde but you can’t hear that moment. In a place in Debussy’s Faune prelude the rhetoric of the music obviously gestures the presentation of a new theme which happens to be not the case, only to give the really new theme so inconspiciously that it passes unnoticed. Etc. etc. …. Such freedoms are possible because underlying relationships are experienced subliminally. In Schoenberg’s later music and Carter’s, what comes across subliminally is the lack of such dynamics. The same with most atonal music: in spite of surface mobility, the overall result is static.

I think Copland’s reaction to a lot of serial music was that it was boring harmonically. I mean, if every pitch in the chromatic scale is equal, a piece completely in C Major would have similar results: too many consonants, as opposed to too many dissonances. I remember hearing live a string quartet of Phillip Glass (no. 5, I think). It basically consisted of arpeggios in B-flat major. It was harmonically as boring as many serial pieces of the 50’s. (Not ALL serial pieces. The ‘Serenata d’estate’, for six instruments (1955) by George Rochberg, for example, is quite beautiful, and it is serial. The difference? The harmonic rhythm is slower.)

Indeed, variety in harmonic rhythm keeps the energy flow going. It is truly incredible that composers were prepared to do away with such an important musical dimension.

I heard a lot of Carter when Barenboim was in Chicago. Did Danny not get it or was it me? Interminable music. That said, I heard Robert Mann play an unaccompanied violin piece ten years or so ago at UW-Madison. I was enthralled. Honestly? I think it’s a counterpoint “thing.”

What do I know? I’m just a simple country band (and orchestra) conductor.

It’s an uneven output, which as an earlier comment suggested , never shook off his neo-classical training , and which often veers towards blandness in later years.

Admittedly, the pot calling the kettle black : Elizabeth Lutyens apparently said of Carter’s music that it was like listening to barbed wire.

With that said try the piano sonata which reminds me of Tippett and Copland, or the piano concerto. The latter being a considerable leap forward from the better known Double Concerto.

So Lebrecht met with Elliot Carter for one hour and felt “empty” by the experience. Apparently Lebrecht had some expectation that went unfulfilled and continues to feel cheated. Put in proper perspective, Mr. Lebrecht simply doesn’t care for Carter’s music, so why should he share such a meaningless and empty experience with us now?

Because it says something of the whole school of thought which is still around in music life and academia.

It seems to me that music composition should not be reduced to mechanics. It is not mechanics. But then again artificial intelligence is having a go at it.

In music, technique is merely a means to an end. When the means becomes the end (‘the means is the message’) it becomes pointles. Atonal modernists were writing AI pieces, much ahead of their time. It’s for a reason that AI is called ‘artificial’ intelligence.

His music contained everything but music. What does Page mean by an upper-middle class existence? He was heir to a fortune (Carter’s Little Liver Pills). If anything, he proves that all composers must learn to perform music before they compose anything. If you don’t understand performance, you don’t understand how music works. Composers have unfortunately created a modern model of abstraction, that you can write music in your head for your own pleasure, and expect others to perform and listen to it.

“He was heir to a fortune (Carter’s Little Liver Pills).”

It wasn’t the pills that built the fortune, but the lace business (import/export) which was very important during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

When I first met him when I was living in St. Gallen, Switzerland, Carter told me himself that his father had had an office there. Most of the fancy lacework was done by women working from their homes for a pittance, and Carter’s father exported them to other countries and sold them presumably for fantastic prices. Automation took over, though, and the market for handmade lace took a nosedive.

There is some interesting reading about it here:

https://www.textilmuseum.ch/en/

Interesting….. there may be a connection between complex lace design and EC’s works. Both forms are surface phenomenae and survive on complex designs.

An astute review which is seemingly marred by this throwaway observation:

“He composed steadily in his own distinctive manner from his teen years……”

He was a late developer as Tim Page acknowledges.

Carter’s early neo-classicism was anything but distinctive and not really much to do with what was to come in his mature years. At a push, I suppose you could argue that the manner remained the same, but the surface changed.

Often atonal modernism is the refuge of composers who are not very good at tonal music. And indeed this has something to do with the relationship between background and foreground (surface): with tonal music, the complexity is in the background and psychological in nature, and in the long-term relationships which are not always very prominent, but define the narrative and structure. Atonal modernism has everything in the foreground (surface) and its complexities are materialistic, not psychological.

Huh. That’s pretty good.

Your idea of foreground and background, I don’t fully get. Also, the term ‘atonal’ is largely misunderstood as tonal centers do exist in this music, but are expressed reverentially. And how can the “complexities” of atonality be more “materialistic” and not “psychological”?

I played a lot of Carter in my time, including more than a few premieres during his last decade. Desire the excitement that surrounded these events, Carter’s music never grabbed me in the way that Milton Babbitt’s did and still does. Then again, I remember turning on the radio during a long drive and being riveted by an extraordinarily interesting string quartet work I didn’t know; it turned out to be Carter’s 1st Quartet.

Carter wrote the music he most wanted to hear. That’s fine. But those later works, at least for me, did not live up to their hype. On the other hand, we should be grateful an composer in this day and age received hype of any kind.