Minimalism was around in 1797

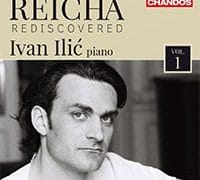

mainIvan Ilic, in his latest video on Anton Reicha, argues that the Czech-French composer discovered minimalism around the middle of his life in a piece comprised of three notes.

Watch.

Man in Glass house.

Ivan Ilic, in his latest video on Anton Reicha, argues that the Czech-French composer discovered minimalism around the middle of his life in a piece comprised of three notes.

Watch.

Man in Glass house.

The US violinist has announced she is still…

We gather that Juilliard has summarily fired a…

The Metropolitan Opera has appointed Daniele Rustioni as…

Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra has recruited its next…

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Bravo Ivan! Thanks for a very enlightening video. The piece in 5/8 is just as extraordinary as the minimalist work. I look forward to the next instalment. PS Norman, very good pun!

In an interview Pierre Boulez was asked about his thoughts on minimalism. His answer was, “minimal”.

I’m not saying I agree with him, I just found it amusing.

Reicha was an interesting composer.

But for a piece to be a ‘forerunner’ of minimalism is not a recommendation. The piece with only 3 notes is, therefore, boring and musically completely empty.

The piece with 5/8 is merely odd and has nothing musically interesting to say.

In these experiements, what really happens, is that Reicha got into the trap of rationalism that was a widespread disease in the 20th century, with comparable results.

The interest supposed to be raised for today in such experiments appears to be based on the assumption that when something is closer to OUR time, it must therefore be better than the average productions of the past: when Reicha began to write sonatas and more normal music, he is supposed to have become more conventional, as if more musical interests are, in themselves, conventional. Implied in such vision of history is the ideology of postwar modernism whichy claimed that there is something like ‘historical progress’ in music, so that one could speak of ‘advanced’ and ‘conventional’ and ‘outdated’ referring to musical works. But ‘progress’ in the arts is only possible in terms of artistic quality and to judge such a thing, historical placement is irrelevant.

I found the fugues of Reicha more interesting, and yes, even in his own time the concept of ‘fugue’ was thoroughly ‘oldfashioned’, but offering much more musical possibilities than three notes.

“The piece with 5/8 is merely odd and has nothing musically interesting to say.”

That is your opinion, John, and you are entitled to it. But I wonder if you looked at the excerpt of the score available on the publisher’s website? Most of the 5/8 section is there, as is the theme:

https://symetrie.com/extraits/ismn_979-0-2318-0783-7.pdf

I just read through these excerpts slowly at the piano, and find them highly unusual and, yes, beautiful. The theme is forceful and arresting. The quintuple section has an affecting, mysterious quality, and the 5/8 meter doesn’t feel awkward at all. Also, it follows the theme strictly, but the changes in register veil the connection. Quite a feat, if you ask me.

You seem to be ideologically blinded by your dislike of Modernism. I’m not crazy about Modernism either, but I don’t think that the video suggests that the conventional music Rejcha wrote is less good. This is just the music he was writing in Hamburg. Your assumptions appear misplaced.

Rejcha’s Opus 36 Fugues are absolutely brilliant, so the idea that there is more piano music out there is exciting. I don’t remember reading any discussion of the following works, so clearly there is more work to do on Rejcha’s legacy:

https://symetrie.com/en/authors/antoine.reicha

Isn’t the trend towards reclaiming the original spellings of east-central European composers’ names, hence Antonín Rejcha? I certainly have a Czech-produced CD of Rejcha that uses that spelling. Likewise Fryderyk Chopin. Once upon a time it was not unheard of to refer to Bedřich Smetana as Friedrich, which now sounds quite ridiculous. To persist in using French and German spellings does seem reminiscent of the mindset behind Chamberlain’s infamous “quarrel in a far away country between people of whom we know nothing”.

Only recently on this blog Anthea Kreston referred to the Polish city of Wrocław as “Wrocław (Breslau)”. This strikes me as a trifle unnecessary, given that Wrocław was incorporated into Poland’s new territory some 73 years ago. Few people much below the age of 80 will even be able to remember a time when Breslau was still German, and yet Anthea Kreston is far from being the only person who persists in using the old name as though it ought to be more familiar than “Wrocław”. (I was interested to discover that Poles are perfectly happy when speaking or writing in German to use the name Breslau, this being taken simply to be the German for Wrocław with no particular historical overtones.)

With respect to Reicha there is a widespread consensus to spell his name Reicha. Only Czech people persist with Rejcha.

Reicha was born in Bohemia but lived most of his life in German and French speaking countries. He spelled his name Reicha throughout his life In this particular case, the decision seems reasonable.

Pronunciation is another matter. This was alluded to in the first video in the series:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0hN3aZXd68

Do you know what the acerbic musicologist (and fervent football fan) Hans Keller said about minimalism? “Show me a minimalist composer and I’ll show you a minimalist talent.”

Sorry, but Vivaldi got to minimalism first.

Bach for elephant

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VOr2O0FfpT8

What an interesting video. More like this!

Is it possible to be more minimalist than a one note composition?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ffZiEgC4Tu0

O yeah?

Try this; you might start at 21:42, or 56:30, or anywhere else. Hill country. Min with true feeling:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBt10AMIRGU

Minimalism was around in medieval music; one example is called ‘isorhythm”.

Absolutely right. Steve Reich has recognized his debt to Perotinus Magnus in an interview some years ago (I can’t find the reference just now).

Wonderful medieval minimalism:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lwgaV0oOkfI

However, 20th Century minimalism is just boring.

Interesting how mistaken they were about cause-and-effect for health problems and that we take their word for it. Moving to a different city is not what causes toothaches.

For an earlier bit of minimalism check out Marin Marais’ “Bells of St. Genevieve”. (1723) Same three bass notes for 8 minutes.

I recall tuning into the local classical station once and catching something that was just the same string arpeggios over and over.

“When did they start playing Philip Glass?” I wondered.

Then the announcer came on to say, “That was the second movement of Vivaldi’s concerto for….”