Bringing my Testore violin back home

mainFrom our diarist Anthea Kreston:

Last night’s concert in Milan was wonderful. I had flown in early enough to be able to have a nice stroll to the Duomo. Climbing the winding stairs to top of the church, I was able to see all of Milan through the hundreds of marble filigree spires piercing the sky, covered in cherubs and all manner of sculpture. The church itself was so ambitious in size and detail – it reminded me in that way of Gaudi’s Sacre Familia in Barcelona – no detail overlooked, too ambitious, too small or too large. The entire, endless floor of the church was made of interlocking colored marble designs, the story-tall oil paintings, the walls of stained glass dwarfed the alters, the intricate mausoleum, the archeological dig below.

Our concert was in the Conservatorio di Musica “Giuseppe Verdi” di Milano, Italy’s largest music school. With a history of over 200 years, it is housed in the cloisters (dating to the late 1500’s) of the attached Baroque Church (Santa Maria Della Passione). As I stood on stage, holding the Testore violin generously on loan to me by a Viennese investor, I was happy to bring this violin home, to the city where it was built over 300 years ago. What would Testore have thought, listening to his instrument playing the brutal, unforgiving Shostakovich 5th String Quartet? In the haunting second violin solos, I have found new voices in my Testore – the opening of the second movement, a slow, desperate, exhausted descending chromatic line, played high on my A string, each descending note a series of the same finger, dripping down, it has a sound up there which cuts to the heart. And again, the third movement begins with a second violin solo – this time low on the G string – empty and yet noble – in the echo I have a new place I can play – if I play with the lightness of a feather, I can move my bow dangerously down the fingerboard, and I found a sound there that is so hollow, so throaty. There is no forgiveness here – if I don’t precisely control my speed, angle and weight of the bow, the sound will crack, squeak, or disappear. But if I have the courage, it can be magic. This is one of the pieces we will record this spring for our Shostakovich CD.

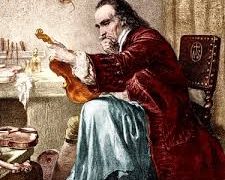

The Testore name has a complex mix of lore surrounding it. The maker of my violin, Carlo Antonio Testore, was a student of the famed Grancino, and the father of a short dynasty of Testores who continued making and selling their instruments under “the Sign of the Eagle”, the family shop the heart of bustling Milan. My Testore was built during the Golden Age of violin making (it is 1710). Back-handed compliments abound for the Testore violins – comments such as “remarkable sound, considering the choice of inferior woods”, “beautifully made, of one doesn’t look too close at the odd-shaped, roughly hewn scrolls”. But – really – what was it like for a Luthier in the Dutchy of Milan during the height of the War of the Spanish Session (1701-1014) – a major European conflict that embroiled the greatest houses of Europe, and went as far as North America, under the name of Queen Anne’s War. Maybe Testore deserves more – give the guy a bit of a break – it can’t have been easy to source materials and retain a violin shop while the world around you was crumbling. Maybe he deserves to be heralded as a maker who persevered under impossible circumstances, who was meticulous while fearing for his life and the lives of his family. Was creative with materials and found his sound in different woods, with unconventional techniques.

Generations of Royal marriages had been negotiated, regal births had cemented territorial rights, the Spanish empire was vast and strong. The much-anticipated death of last Hapsburg King of Spain, the sickly and childless Charles II threw the conflicting kingdoms of France, Austria and Bavaria into a path of war, using the resulting instability to reclaim or claim new lands. I can hardly imagine that a violin maker would have the freedom of movement to travel and source the aged maple favored by Testore’s southern luthier rivals – he opted for locally grown “oppio” maple instead, and spruce. While the world around him was violent and bloody, while his very city was used as a bargaining tool, he stayed, bent over his workbench for 500 hours per instrument, intent on his craft. My violin was born of this determination, this blind passion, and it continues to shine, playing its heart out next to the vastly superior Stradivarius to my right and Amati to my left, and defiantly holding its own.

Thank you, Anthea. I especially love your second paragraph, your descriptions of finding some of the voice(s) of your venerable instrument. The historical perspective on Testore’s world is fascinating food for thought.

Thank you for your lovely essay. I enjoyed reading the historical background surrounding Milan in Testore’s day. I have owned a cello by Carlo Giuseppe from 1721 since 1971. Carlo Giuseppe was the father and founder of the luthier dynasty and Carlo Antonio was his son, as well as Paolo Antonio. Sorry to have to correct you on that point because I enjoyed the read otherwise. My cello has held its own for these 47 years I’ve played it professionally and has been much admired and I have found much in its voice as well.

Julie –

You must love yours! I adore my badly made scroll. You are right – mine is by that father – 1710… got my Carlos tangled.

Hope our instruments can meet some day!

Anthea

I was just waiting to hear it got smashed by an airline. What a change that it wasn’t.

Here’s a question: do the airlines smash up cheap, worthless instruments or only the valuable ones?

Oh Anthea, this is such wonderful writing! The music, the player, the instrument, its history, and the place … it all comes so wonderfully together. Thank you , thank you!!

Totally agree. And what I’d also like to know is how you come to play Shostakovich and then, say, Beethoven perhaps within a week or so of each other. Are all these works already known from memory or, at least, already very familiar? How does this performance process work?

“But if I have the courage, it can be magic.” This is true in sounds and words, Anthea. Thank you for both. I hope my 1741 CA Testore viola can meet your violin some day.

I think the problem with Testore is they can be so variable and uneven.

Some can be superb in the upper registers but lacking low down.

Other’s can be totally unbalanced all over.

Some rare ones can be superb balanced instruments but fragile and difficult to set up.

Why?

There are actually better instruments made by much less well known makers.

(Carcassi springs to mind).

In answer to your question, a good luthier or teacher should be able to help you.

Marvelous

“There is no forgiveness here – if I don’t precisely control my speed, angle and weight of the bow, the sound will crack, squeak, or disappear. But if I have the courage, it can be magic.”

This is what a great instrument does: it puts out exactly what you put in. Lesser instruments are less sensitive, so you have a little margin for error before something bad happens.

I like to say that playing a great instrument is like having a very strict teacher always in the room with you, scolding you (by sounding bad) the moment you do anything wrong.