Death of a US composer, 85

mainThe moderate Chicago modernist Alan Stout died on February 1 after several years in a care home.

He received four world premieres from the Chicago Symphony and others from Baltimore (his home town) and the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Among his students at Northwestern University were Augusta Read Thomas and Joseph Schwantner.

Stout was an enthusiast of Boulezian post-serialism, while maintaining a keen interest in Sibelius and other Baltic composers.

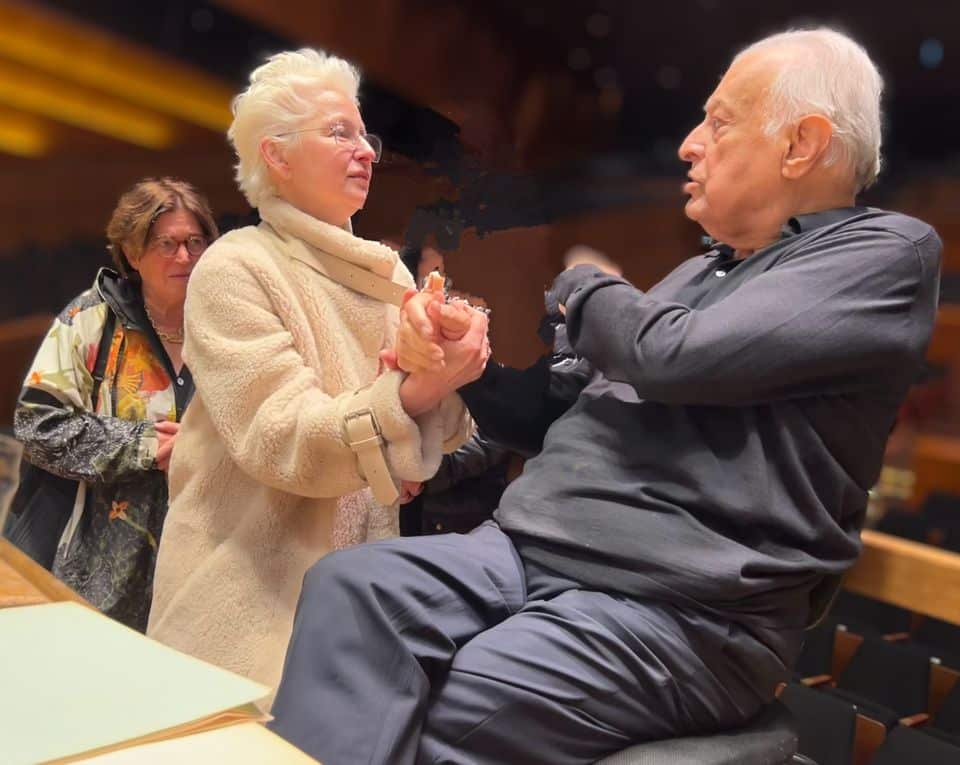

Tribute here.

Comments