Death of a New York opera composer, 91

mainThe tonal composer William Mayer, best known for a prize-winning opera A Death in the Family, died at home in Manhattan on November 17.

The tonal composer William Mayer, best known for a prize-winning opera A Death in the Family, died at home in Manhattan on November 17.

It’s lawyers at dawn in the Deep South…

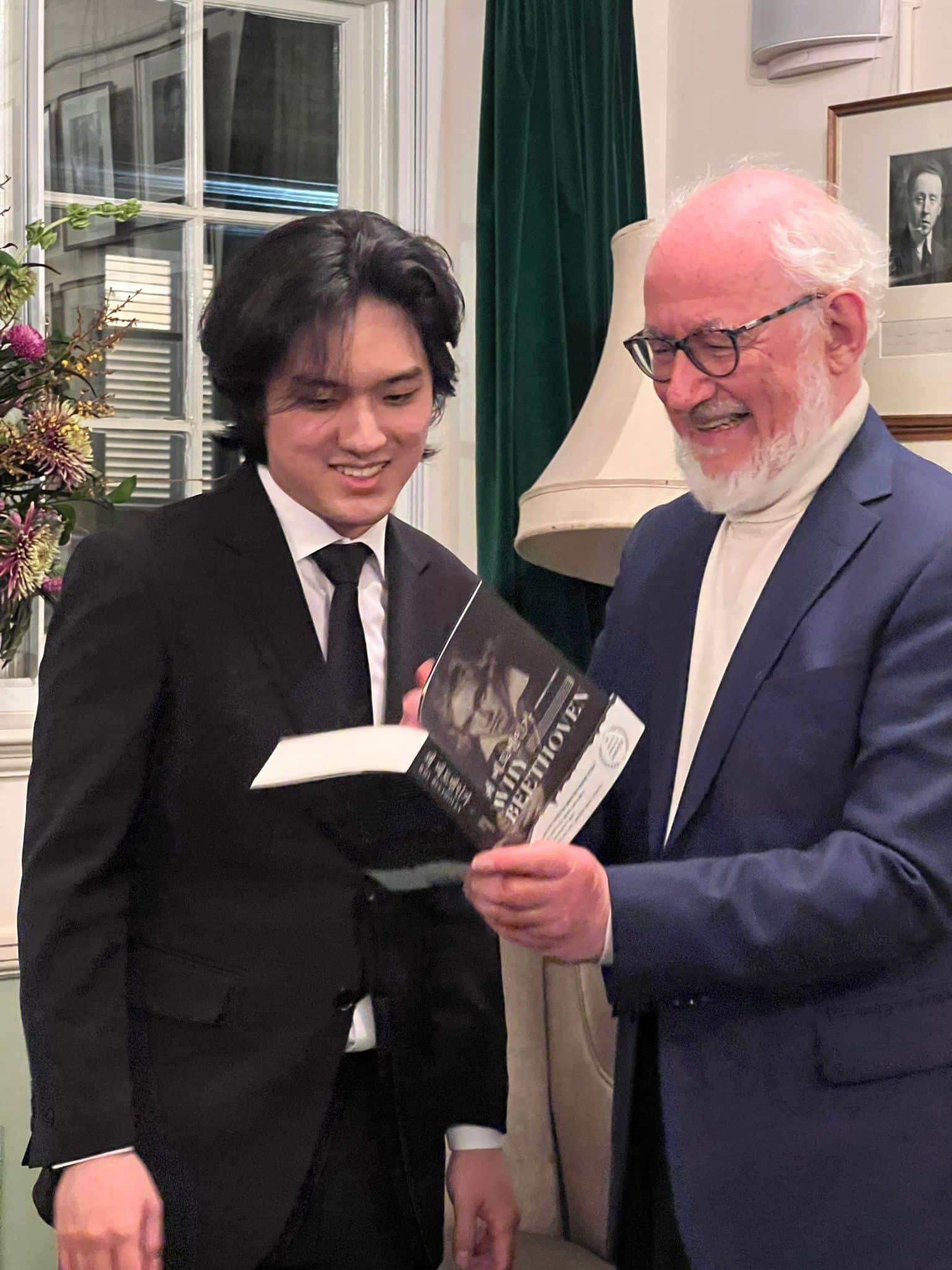

Last night, Yunchan Lim gave a recital of…

After last night’s Wigmore Hall recital, I had…

The Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra will give a…

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Comments