Were composers freer in Russia than in the West?

mainFrom the latest Lebrecht Album of the Week, a 5-star:

In the dying years of the Soviet Union, I became aware of dozens of symphonists who survived on the fringes of musical society, tolerated by the authorities but never given a proper hearing. Once I got past the immense, historic figures of Mieczyslaw Weinberg and Galina Ustvolskaya, both pivotal in the life of Dmitri Shostakovich, I kept discovering other samizdat composers who, for some reason, seemed to speak my language. At a time when western musicians were subjected to a dictatorship of style and serial ideology if they wanted to get on the BBC, these covert Russians were free to write as they pleased….

Read on here.

And here.

And here.

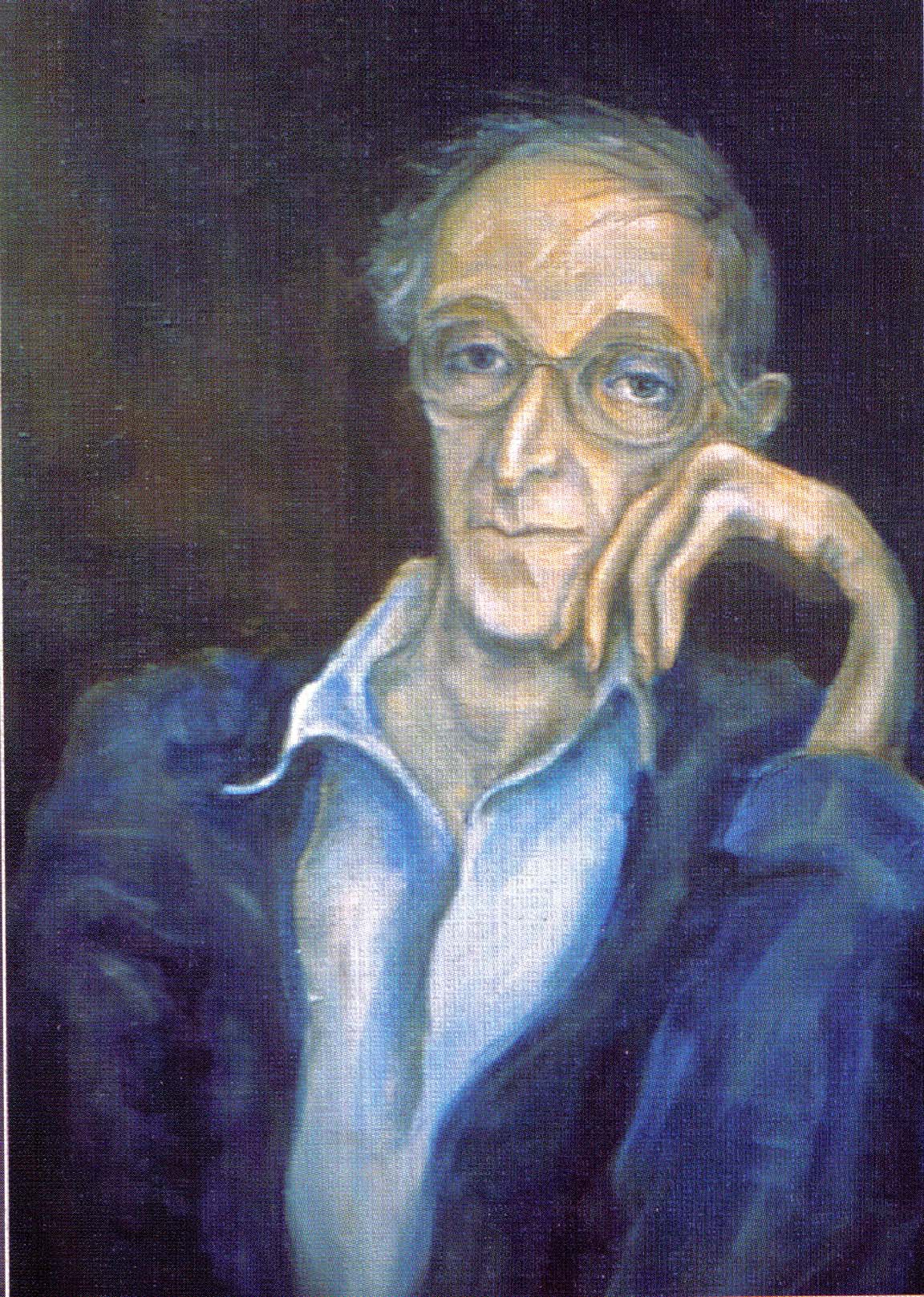

Portrait by Tatyana Apraksina

The 1st and 3rd links work, but the 2nd is “Error 404 – Not Found”

The URL of the 2nd link was pasted twice, back to back, resulting in an invalid link. Deleting the one of the two is necessary to open the link (below).

http://www.openlettersmonthly.com/norman-lebrechts-album-of-the-week-lokshins-clarinet-quintet/

How did these covert composers earn a living?

If all performance, publishing and recording was controlled by the government, how did they make money?

Was composing just a sideline to some other day job and what was it? Lokshin’s Wikipedia bio mentions some brief service as a fireman during WWII; I’m sure that was not lucrative.

That Wikipedia bio also says:

At the height of the anti-cosmopolitism campaign and music purges of 1948, directed by Andrei Zhdanov, Lokshin was expelled from the Moscow Conservatory for the popularization of what was considered the ideologically alien music of Mahler, Alban Berg, Stravinsky, and Shostakovich among his students.[2] The efforts of Nikolai Myaskovsky, Maria Yudina, and Elena Gnessina to get him another job were in vain. For the rest of his life Lokshin supported his family by composing music for film and theater.

I’m listening now to his String Quintet in Memory of Shostakovich.

“film and theater”… those are government jobs, too, in the Soviet Union, right?

Everything is a government job in the Soviet Union.

Of course it was, and therefore the salaries were determined by the government too. The famous joke was: we pretend to work and they pretend to pay us.

Lokshin spent most of his career in a no man’s land. He was suspected of having been a KGB informer, who denounced, among others, the mathematician and dissident Esenin-Volpin (son of the poet Esenin). Richter warned people not to socialize with Lokshin, because “he’d have you imprisoned”. Rozhdestvensky refused to conduct his music, demanding a “written proof” that Lokshin wasn’t an informer. So for the liberal intelligentsia and many of his fellow musicians, he was a persona non grata. Only a few of Lokshin’s colleagues – Maria Grinberg, Maria Yudina and Rudolf Barshai – continued to support him. On the other hand, to the authorities he was an ideologically alien modernist and aesthete. The man eked out a living writing music for documentaries and doing arrangements and orchestrations of other people’s works. Today, it is generally believed that Lokshin was the victim of KGB’s diversionary tactics – they artfully spread the rumors about his supposed collaboration to protect the real informer.

“Rozhdestvensky refused to conduct his music, demanding a “written proof” that Lokshin wasn’t an informer. ” –

There are recordings though of Rozhdestvensky conducting Lokshin. So, he received the written proof, then?..

Apparently, the story of Lokshin’s supposed collaboration with KGB wasn’t known to Rozdestvensky until the 1970s. However, demanding a written document was the kind of behavior Soviet authorities excelled in – cynically setting insuperable barriers to their citizens. Who was supposed to sign such a letter – maybe Andropov or Brezhnev ? (I would like to qualify the above by stating that this quote by Rozhdestvensky appeared in several articles on Lokshin I’ve read. I cannot, of course, be sure that Maestro Rozhdestvensky, a great conductor and a man of highest ethical principles, actually said this.)

How sad…

The great irony of the Cold War music politics was, and still is, that under communism the tonal tradition was imprisoned within totalitarian government restrictions, while in the West people did not need such intervention to get composers in line: they could do that perfectly well themselves, with the help of musicologists who, following modernist ideology, provided the arguments to prop-up the avantgarde and sideline any critique as ‘conservative’ and based upon ‘not understanding our time’. (People like Adorno and Arnold Whittall have done immense damage to music and its perception.) As in Russia modernism was suppressed, in the West new music which still kept to the fundamentals of the art form was condemned as ‘irrelevant’ to the ‘march of history’ of which avantgardists happened to be in charge. The ‘freedom ‘and ‘pluralism’ as advocated by modernism, were pure lies, covering-up an entirely totalitarian mindset.

‘I’m for 300 percent Leninist’, a certain French avantgarde composer and agitator proclaimed, thereby inspiring hordes of would-be composers to man the barricades of progress, and shooting-down any remnant of the decadent past – which the central performance culture calmly continued to present.

In the name of freedom, a ‘hetze’ was carried-out against the musical tradition, to make sure new music would begin again from scratch. The scratching we still hear around us, albeit in the margine of music life where the musically-challenged can still exercise their hobbies, paid for by the state.

“(People like Adorno and Arnold Whittall have done immense damage to music and its perception.)”

+1 and thank you for saying this !

Especially Whittall paints it purple: “… the common conclusion is that the modern age…. is simply not an age in which worthwhile art can be expected to flourish”. (In: ‘Music since the First World War’, talking about the 20th century in general.) So: out you go, Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Strauss, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Scriabine, Poulenc, Szymanowski, Britten, etc. etc. etc. – they all wrote music not up to Dr Whittall’s standards.

The answer to the headline is a categorical NO.

Right? I don’t understand why one would choose that for a headline