Whatever became of Bill Schuman?

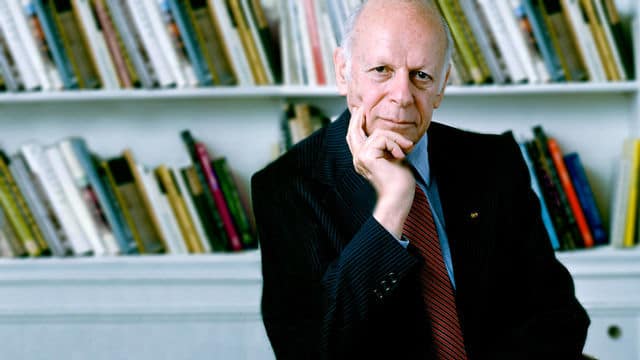

mainAnyone alive in the 1960s will remember William Schuman, a power in the land of American music.

President of Juilliard and the Lincoln Center, he won two Pulitzer prizes and a National medal for the Arts for his abundant orchestral music, which included ten symphonies.

Not a note of his gets played nowadays. Chicago psychotherapist Gerald Stein wonders why.

In his day (1910-1992), only Aaron Copland was a more prominent living American composer in the classical world. Moreover, as president of the Juilliard School and then of the emerging Lincoln Center, no one had a greater influence on serious music in the middle portion of the last century. Schuman also wrote 10 symphonies among other works, and won the first Pulitzer Prize ever given for musical composition. His Symphony #3 is arguably the greatest such piece written by an American.

Read on here.

Still perplexed? Read Bruce Duffie’s interview with Schuman here.

Early on I said to myself,“You can do anything else that you want to do, but you have to find between six hundred hours and a thousand hours to be alone in a room.” That’s a sine qua nonof the conditions for composing, as far as I’m concerned. So I used to keep a little diary of time. I’d go to the school maybe at 8:30 in the morning, having worked for an hour first, so I’d put down one hour. Or, if I went at 11:23, I’d put down two hours and twenty-three minutes. By the end of the week I’d add up the hours and the minutes that I actually worked, and by the summer time I would usually have about three hundred hours chalked up. Then, of course, in the summer time I had more time to work. I rarely reached a thousand, but it was never less than six hundred. It sounds like a very cold way of going about it, but it was the only practical way that I could devise of assuring myself the time; the reason being that everything else you do is so much easier than writing music.

Comments