Vienna and Berlin unite in Harnoncourt sorrow

mainSalzburg is flying a black flag over the Festspielhaus today. ORF changed its programming. France Musique is playing only Harnoncourt all day. And tributes are pouring in for a man who changed the musical world.

From the Vienna Symphony Orchestra:

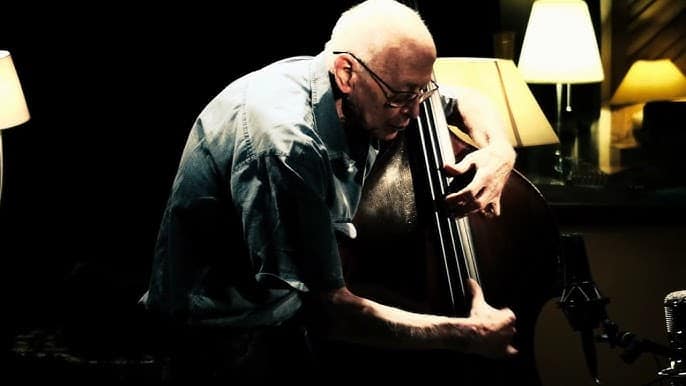

A great loss for the musical world: Nikolaus Harnoncourt died yesterday. He was cellist in our orchestra under Herbert von Karajan and Wolfgang Sawallisch from 1952-69. As a conductor he led us in 91 concerts and performances between 1983 and 2008. We are deeply grateful for sharing these and innumerable magical moments and experiences more with him. He will never be forgotten!

From the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra:

With great sorrow, we received the news of the death of our Honorary Member Nikolaus Harnoncourt while traveling from Bogotá to São Paolo. The Vienna Philharmonic takes a deep bow before one of the greats. After Nikolaus Harnoncourt, nothing is the same as it was before. We will miss his unique perspectives, his out of the box thinking and the manner in which he plumbed the depths of the human soul. Under his baton, we experienced many compositions, from Johann Sebastian Bach to Alban Berg, in a completely new light. His groundbreaking interpretations pushed us to our limits and beyond. They affronted us, they unsettled us – and they convinced us. We extend our deepest sympathy to his family. Without his wife, Alice, the cosmos of Harnoncourt would not have been possible.

From the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra:

The Berliner Philharmoniker are much saddened by the death of Nikolaus Harnoncourt, who died on 5 March at the age of 86. Ulrich Knörzer and Knut Weber, members of the orchestra board: “Nikolaus Harnoncourt, conductor laureate of the Berliner Philharmoniker and recipient of our Hans von Bülow medal, embodied the vitality of classical music more than almost any other. The unquestioning acceptance of tradition was a horror to him. With unrelenting curiosity and freshness, he illuminated and questioned musical scores again and again. In this way we learned an immense amount from him – also, and particularly, with regard to repertoire which we have played from time immemorial. This process was even more fascinating for us as it was not limited to philological discussion. It was Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s gift to transform his amazing knowledge into fantastically lively music making. Even his last concert with us, a Beethoven evening in October 2011, was of undiminished intensity and will be remembered by us as a highlight of our work together. Nikolaus Harnoncourt was in the truest sense an incomparable musician and a wonderful, close friend of the Berliner Philharmoniker. We will miss him enormously.“

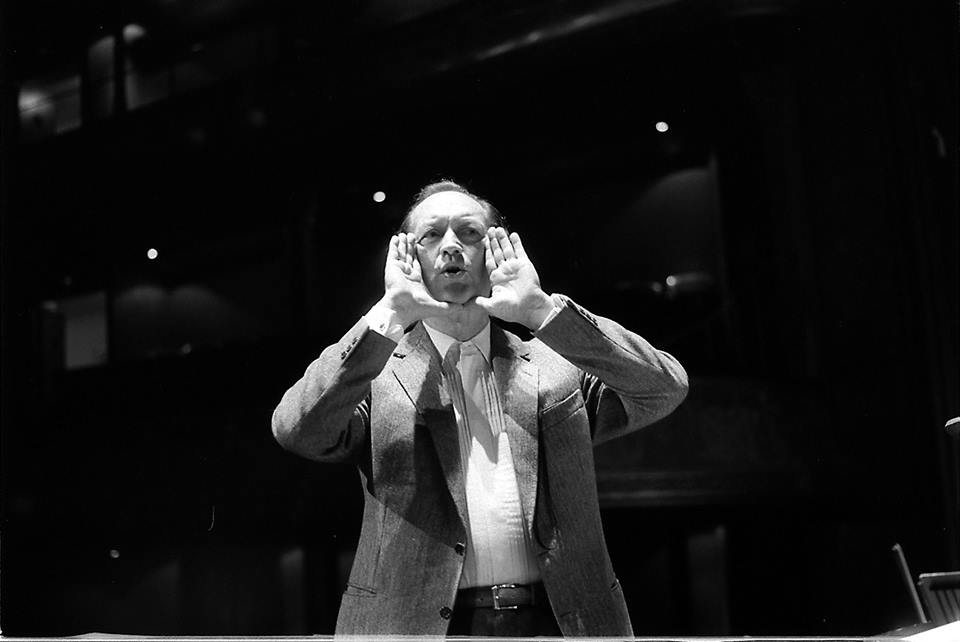

photos (c) Marion Kalter/Lebrecht Music&Arts

Gidon Kremer writes: ‘Nikolaus Harnoncourt, with whom I shared many intimate moments in music by Mozart, Schumann, Beethoven, Brahms and – especially – Alban Berg, was always the most generous partner whose presence inspired me to focus on the deepest substance of the scores we performed and recorded together.

Lang Lang writes: ‘I’m in shock today over the news of Maestro Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s passing. He was such a special, genuine, sincere, and talented musician and human being. He taught me so much and opened up musical doors for me – especially with Bach, Beethoven, and of course, Mozart.’

Franz Welser-Möst: ‘An interpreter who changed our world more than any other over the past 50 years.’

Thomas Hampson: An immense loss for the musical world: Nikolaus Harnoncourt … was more than a conductor, a cellist, an “early music specialist”. Nikolaus Harnoncourt was one of the most enlightened souls I have ever met and had extraordinary influence on generations of musicians. His unbridled curiosity, relentless search for the truth of the matter, his egoless risk of the moment, founded in that staggering renaissance knowledge of music as the language of life’s limitless questioning, have set him apart. Nikolaus Harnoncourt was a pioneer, a rebel and a deeply profound soul. For all of these reasons and so many more, Nikolaus fundamentally shaped my own re-creative process and how I listen and think about music.

Thank you, dear Nikolaus, mentor and colleague, for sharing your light, your passion and your fire with all of us so generously and thank you for a beautiful personal friendship that started more than 30 years ago. We will miss you beyond description, but your legacy will live forever in all those you touched. Mine and Andrea’s deepest condolences and love abide with your precious wife Alice and of course to your entire family.

Nikolaus once said that “the Arts are the umbilical cord to the Divine”. Surely he now rests in everlasting Divine Peace.

From the Salzburg Festival press release (a conflation of equivocations):

Harnoncourt’s career in Salzburg … From 1972 he taught performance practice and historical instruments as a professor at the Mozarteum. His first performance as a conductor in Austria took place thanks to the Mozart Week, where he conducted the Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam in 1980. The Mozarteum Foundation was also responsible for his debut with the Vienna Philharmonic. After all, Herbert von Karajan did not want him to appear at the Festival during his lifetime. Karajan and Harnoncourt – those were separate musical worlds. However, they did have one thing in common: they were both after truthfulness in music. Both remained seekers throughout their entire lifetimes, but their searches took radically different paths.

In 1992 the time had finally come, and Nikolaus Harnoncourt first stepped onto the conductor’s podium at the Salzburg Festival.

Could you please explain the headline? How do they unite?

I disagree with Salzburg Festival’s statement that both Karajan and Harnoncourt were looking for “truthfulness” in music. This construct of “truthfulness” in music would need definition. What is it?

The only truthfulness in music is being truthful to one’s own musical perception and ideas. And how much the result of that speaks to others, defines the success of many famous musicians.

Where one places his own ego in the hierarchy, above all, among colleagues, below everybody as a servant, doesn’t change anything about this fundamental principle of musicianship, it only changes the sympathy one has for others.

Would you please provide me the direct link to the Salzburger Mozarteum’s and/or Salzburger Festspiele press release stating that Karajan did not want Harnoncourt at the Festspiele?