Max was so extreme he made young Prokofiev seem mild

mainA 45-year memoir by the pianist Peter Donohoe.

Sir Peter Maxwell Davies emerged from that great era that followed World War Two – albeit not immediately – when a new generation for around 40 years – up until circa 1979 – grew up to question everything, when fear of the future expressed by artists and musicians was even greater than it had been between the wars, and when the power to shock and rebel using the resources that became available at the time eventually extended to film, radio, TV, pop (later, ‘rock’) music, and the classical music avant-guard. Max represented that generation so well that he became almost the ‘classical music’ equivalent of the ‘shocking’ characters of Mick Jagger.

I first encountered him when he brought The Pierrot Players to a venue situated next door to my school – Chetham’s in Manchester – circa 1970. How the concert came about I know not – perhaps part of an Arts Council Contemporary Music Network that included a booking at the Manchester Teacher Training College, situated immediately next to the school at that time.

Max’s own music, as far as I remember, comprised most, if not all, the program (memory somewhat fails me), and included Eight Songs for a Mad King and his ‘realisation’ of Purcell’s Fantasia and Two Pavans. The concert had a profound effect on me, as the dramatic effect of everything about the music and the persona he projected at that time was so extreme; it would have been shocking beyond words to the majority of a music school steeped in pre-WW1 classical music, had many others attended it – one member of the music staff and her future husband plus three pupils, myself included, went.

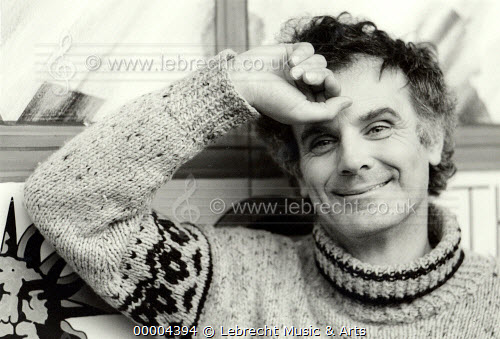

His personality at that time – perceived by me from afar as I was too shy to actually speak with him – was that of an extreme ‘enfant terrible’ – one so extreme that he made the young Prokofiev seem like nothing by comparison, with very disturbing intense, intimidating eyes and wild curly hair, a very angry anti-establishment point of view about many things outside the music world, and a determination to shake up and attack the complacency of the older generation regarding music itself. I identified with the persona he projected easily at the time, despite our age difference.

My next live experience of him was at the 1974 Dartington Summer School. The retired Controller of Music for The Proms, Sir William Glock, a great champion of Maxwell Davies amongst many others, was the then director of Dartington, and he was ultimately succeeded by PMD. [It was rumoured that he had insisted on bringing a coffin with him to sleep in, as a protest against the hard beds provided at Dartington, but this may have been a Chinese whisper – as tend to circulate around shocking characters.]

That year Max’s chamber group – by then renamed ‘The Fires of London’ – visited for one concert, whilst Max himself stayed for the whole period, lecturing in composition. I can remember a reference to Chopin’s Ballade No 4 that revealed open admiration during one of his lectures. I mention this because it has always been a pillar of my own approach to Twentieth Century music that its composers, almost without exception, realised the degree to which they stemmed from the past; although sometimes in their youth they posed as if to reject the universally accepted great composers, when they grew up they accepted and embraced the very music they had previously appeared to stand against. This was in my experience the first time a revolutionary composer of our time had stated it openly, breaking my impression of the then often maintained ghettoisation of all styles and periods, although I now realise that it had been obvious for decades regarding virtually all of them. [I do hope those of the Twenty-First Century will be seen to be so humble in retrospect….]

Apart from the stunningly shocking aspect of the performance – this time I believe including Miss Donnithorne’s Maggot – he delivered a pre-concert talk in which, amongst other things, he talked about his recent relocation to Orkney, where he told us that it was so quiet that he could hear the muscin his hand moving – ever the dramatist, the thought-provoker, and in his own way slightly naïve. His devotion to Orkney did not however define him as a recluse; he founded his own festival – the Festival of St Magnus – he became involved as resident composer and guest conductor in several places, and maintained two apartments; one in central Edinburgh and one in Kings Cross, London [perhaps my notion that he was naïve was naïve…..] He was heavily involved in an extraordinary variety of projects all over the world, too numerous to mention here, as well as continuing to write music prolifically.

Everything about him seemed provocative and extreme, and I so happily followed him from afar as I felt much the same at the time. His life in Orkney, along with growing older, changed him so much that he became a very approachable and likeable man, albeit with very strong political views and a very firm and genuine commitment to education and the value of music therein. He did in no way ever allow his angry views as a young man to become diluted by his own success and ‘maturity’; anyone who suggests that he did so by accepting a knighthood and the post of Master of the Queen’s Music is missing the point of those honours entirely.

His series of ‘Strathclyde Concertos’ – were dedicated to and first performed as he wrote them by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra conducted by the composer himself. Five of these first performances were coupled by a visionary SCO management, not only with a classical orchestral work also conducted by PMD, but also a Beethoven Piano Concerto played and directed by myself. This was a very good way of attracting an audience to new music, of making a very fine contemporary composer – who had made Scotland his home and the inspiration for so much of his music – very much part of the community, and associating that often still very extreme composer with universally accepted popular and traditional repertoire. The works’ connections were very apparent from hearing them side by side, and the programs were constructed with great integrity.

This series was not only performed in Edinburgh – the orchestra’s home – but also in Glasgow, Aberdeen and Dundee. Travelling by road to the dates outside Edinburgh gave me the opportunity to get to know Max a great deal better, and he was as charming a man as I had ever met.

During those conversations I was particularly intrigued by his attitude towards Thomas Pitfield, who had been landed with the ‘mission impossible’ job of teaching Maxwell Davies, Harry Birtwistle, Sandy Goehr (my former university music professor), Elgar Howarth, John Ogdon and David Ellis at the Royal Manchester College of Music in the late 1950s. My interest in this stemmed from a) what I had gathered in the interim that all of them had rather cruelly rejected Pitfield as old-fashioned and of the ‘Cow-Looking-Over-A-Farmyard-

My own excursions into his music have not, sadly, been extensive; I do not pretend to be a huge fan of his piano music, although I did tour his post-Schönbergian Five Pieces Op 2 extensively in 1983. However, I always admired many of his orchestral and chamber works; conducting Eight Songs for a Mad King and A Mirror of Whitening Light with BCMG in 1989 was in the event an extraordinary learning curve with regard to how to rehearse with musicians who were under such consistent, relentless strain as they are for virtually the whole of both pieces. Maxwell Davies – like his wonderful older contemporary Sir Michael Tippett – never felt the need to make his musicians’ job comfortable.

The last time we met, Max conducted Ravel’s Left Hand Concerto in his own 60th Birthday celebration concert with the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra. It was chosen as it was said at the time that it was Max’s favourite piece of music from earlier times. [As it is deemed to reflect Ravel’s own dark feelings about the future during the post-WW1 years so intensely, it seems very appropriate when remembering those of Max’s earlier works of the post-WW2 era, but in addition it is also one of the most extraordinary works of the Twentieth Century on all levels – other than length.]

It was my own first ever performance of this work, and my memory failed me at one point – managing to come in one bar early at the beginning of the central section. How they did it I will never know, but Max and the orchestra simply jumped a bar unanimously, and the mistake was completely undetected by almost anyone who was not playing – something which has rendered it necessary for certain members to remind me of every time I go near the orchestra by singing a series of seven descending quavers in 6/8 time at me. Conducting was not really PMD’s forte, but the performances he gave of music by other composers as well as his works were still excellent as a result of musicians’ admiration for his music and liking for the man.

There were many stories about his life away from composing music, some of which – like the one regarding the coffin at Dartington – may have been exaggerated. There was something about his having put his relationship with the Royal Family at risk by supposedly eating swan and chips or swan terrine or some such [apparently eating swan is against British law.]

Some, however, were not funny at all, including a story of an alleged major swindle perpetrated by one of his administrators with regard to his royalties.

It was with horror that we learned of his leukaemia – the disease that has now finally killed him. The music world has lost a splendid visionary composer whose works absolutely reflect the ethos of the era that spawned him, musicians have lost a fascinating and thought-provoking colleague, and the world has lost a very fine man who really did make a difference.

Comments