The secret Soviet history of Pierre Boulez

mainIt was 49 years ago today that the BBC Symphony Ochestra landed in Warsaw for an East European tour, only to hear from the Russians that one of their two conductors was unacceptable.

Apparently, Gosconcert had assumed that Pierre Boulez was the assistant conductor to Sir John Barbirolli until some sharp-eyed ideologue spotted that he was a dangerous modern composer. The BBC were ordered to replace him.

By this time, they were on a flight to Moscow. On arrival there was a frosty champagne breakfast meeting with Gosconcert in which the BBC executive William Glock and the tour organiser Lilian Hochhauser were told once more to send Boulez home. Glock, Lilian tells me, stood up and said ‘if he goes, so does the orchestra.’

The Soviets backed down. Next, they objected to a Webern piece on the programme. Boulez agreed to replace it with an earlier Webern work, opus 6, which the commissars foolishly assumed would be less offensive.

In Leningrad, Boulez conducted his own piece, Eclats. The audience had never heard anything like it before and demanded an instant encore. ‘It was packed,’ says Lilian, ‘they were hanging off the balconies’.

Various Russian musicians have told me down the years that this was the moment their world changed. Suddenly, they realised there was more to music than the regime would let them believe.

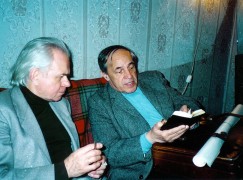

At night in Moscow, Edison Denisov led a small group of composers up the back stairs to Boulez’s room in the Hotel Ukraine. Denisov began teaching his music secretly to select students. He kept in touch with Boulez and, on a return visit to Russia in 1990 (pictured), introduced him to the next generation of composers: Smirnov, Firsova and and more.

It is one of Boulez’s least-known achievements, but he helped to bring down the Soviet Union.

(c) Dmitri Smirnov

Comments