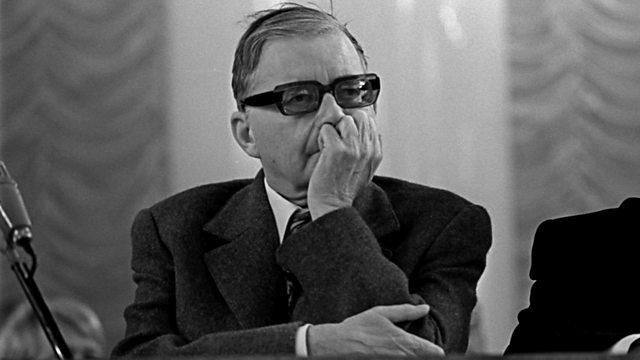

Leonard Slatkin prepares to leave Detroit

mainHe has signed a one-year extension to 2018 after which he will be known as Emeritus Music Director.

Slatkin, 71, says he’s done what he can: ‘I’m very proud of what everybody has done. There wasn’t too much left to do in terms of new initiatives. This is exactly the right time to think about turning it over.’

In fact, he’s changed the weather. After surviving near-bankruptcy and a bitter strike in 2011, Slatkin and DSO president Anne Parsons rebuilt both the orchestra and its audience.

They hired 30 young players, including all principal positions, and attracted the student community with a $25 come-anytime card. They put on events for young people with disabilities. They streamed concerts worldwide and earned the Detroit Symphony its highest international profile since the auto industry heyday.

Scanning Slatkin’s 40-year career as chief conductor – St Louis, London (BBC), Washington DC, Lyon – Detroit is where he has made a lasting difference.

This weekend, he conducts Mahler’s Resurrection. That’s what he has achieved in Detroit.

Comments