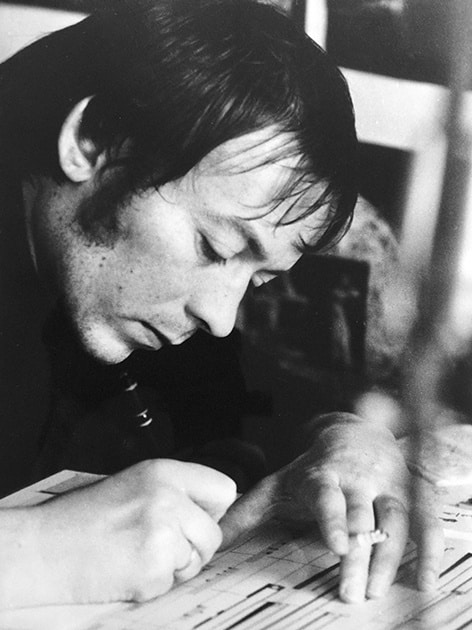

Tim Page: On premature audience ejaculations

mainSeveral maestros have now made the point on Slipped Disc and elsewhere that audiences ought to be allowed to express their reactions in between movements of a musical work.

Among them are Esa-Pekka Salonen, Leonard Slatkin, Mark Elder and Daniel Barenboim.

It may be time to abolish the mid-movement taboo- with certain qualifications.

Our friend Tim Page has been reminded of a piece he wrote almost 30 years ago in the New York Times, imploring concert audiences not to erupt too soon. We reprint it below with his permission, and one emboldened phrase.

EARLIER this season, I sat with a rapt audience at Carnegie Hall, listening to Mahler’s Symphony No. 9. Written during the composer’s final illness, the symphony provides one of the most difficult, haunting yet ultimately rewarding musical experiences in the repertory. When the final notes of the closing Adagio dissipate into air, the silence should be as eloquent as the sounds have been – a charged residue, if you like; a silence that is a musical statement in itself, transfigured by what has gone before. At Carnegie, Mahler’s silence, so hard won, lasted barely a second. Somebody shouted ”Bravo!,” the audience responded reflexively, and one left the hall frustrated, rudely shaken from an engrossing dream.

Premature applause is one of the most disturbing elements of our musical life. I have long despaired of hearing the final notes of the first act of ”Der Rosenkavalier” in an opera house. It is a wonderfully poignant moment, and it is inevitably interrupted. The Marschallin sits at her mirror, worrying about her lover, feeling mortal. The curtain slowly starts to fall, and the exquisite cadence Strauss created to accompany its drop is suddenly lost in applause. Ironically, the better the performance has been, the more quickly it is likely to be disrupted.

Will I ever attend a performance of Schubert’s ”Trout” Quintet in which the playful false ending in the last movement isn’t broken by ill-timed cheering? The fans vie to shriek the first ”Brava!” at diva concerts, and a recent performance of Debussy’s ”Clair de Lune,” was marred by clapping the moment the final note was played – the musical equivalent of a photo finish.

Music is not a sporting event but, at its best, a taste of the sublime; the most abstract of the arts, it is, paradoxically, the most human. Jean Sibelius asked that his Symphony No. 4 be followed by no applause whatsoever, and that the audience leave in thoughtful dignity. Glenn Gould once titled an article ”Let’s Ban Applause!” Most of us would not go this far, but applause can be ruinous unless it is carefully considered.

Applause between movements or sections of a song cycle is bad enough (I recently attended a rendition of Schumann’s ”Frauenliebe und Leben” in which every single song was bravoed, handily sapping the score’s collective power), although a polite note in the program guide or a shake of the head from the artist will usually discourage such transgressions. But what can one spectator do to still premature applause without seeming to shush, hector and hamper one’s neighbors, who have, after all, paid for their tickets and are legitimately entitled to express their pleasure?

A plea: hold the applause until the music has completely died away. Wait for that relaxation of a conductor’s shoulders, the drop of a pianist’s hands or the easy grin that releases singer from song cycle. And then applaud as long and loudly as you wish. Your enthusiasm will then complement the music, rather than diminish it.

(c) Tim Page, May 1986

Comments