Whatever happened to mid-century music?

mainIn a shrewd and affectionate TLS review of the second edition of the Grove Dictionary of American Music, the composer Stephen Brown makes a telling observation about the ephemerality of classical reputations.

He writes: ‘It is curious that mid-century modern is now such a sought-after furniture style, while mid-century modern music is rarely heard in appropriately furnished living rooms.’

He continues: ‘Of which American composers can we say that “much of their music has continued to be performed” a generation after their deaths? Roger Sessions? Vincent Persichetti? Walter Piston? Roy Harris?’

One could say the same of mid-century Europeans: Martinu, Frank Martin, Hartmann, Malcolm Arnold, Maderna.

Now why is that?

The (hilarious) picture offers one answer: the furniture looks very dated, without redeeming features which would give it real aesthetic value for other times (it will never become ‘antique’), it merely offers superficial nostalgia for a time when ‘modern’ was still full of confidence and hope (comparable to the sitcom ‘That seventies show’). The music of that time fell in between two stools (of the seventies type): on one hand, modernism which did not offer much musical interest, and on the other, a hesitating traditionalism reworking the leftovers of a former generation. That, in combination with the commercial routines of the ‘music business’, sealed the fate of much music from that time.

Nowadays much music from the 1st half of the last century is being rediscovered: in that period there still was much interesting going-on. Maybe in 50 years time composers from the seventies will be dug-out and get a second life.

John, I usually like your comments and agree with you about Boulez, regietheater and other issues. I even read some good articles published on your personal website.

But let me tell you: you don’t know anything about design. Saarinen’s Womb chair is great.

The chair pictured will certainly give comfort to the butt, and is more human than the ‘sitting machines’ of modernist ideology ( http://www.rietveldoriginals.com/en/collection/ ), but in comparison to the average furniture of the past it is lacking aesthetic invention and taste.

The last century saw, in any field of design, a ‘cleansing’ of ornaments and an orgy of ‘functionalism’, while forgetting that aesthetics is also an important function in creating the human environment.

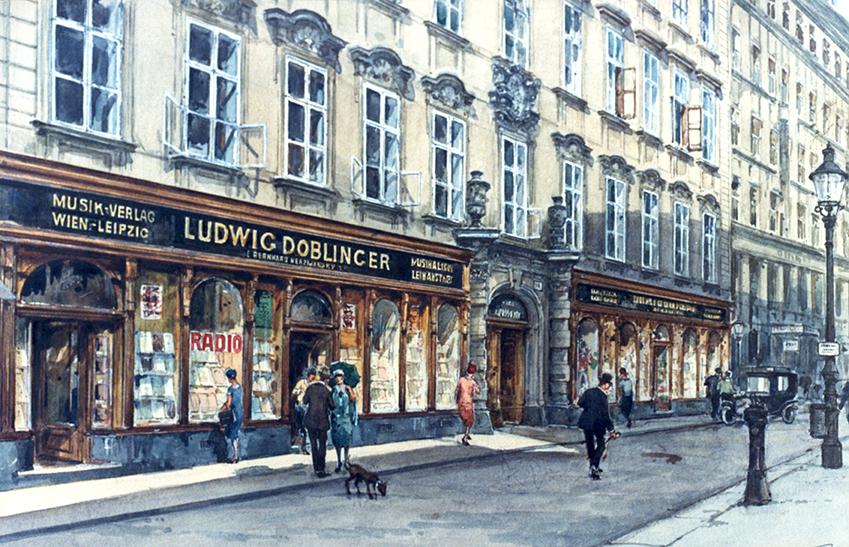

This was not always so:

http://imgadvisor.com/pages/f/french-empire-furniture.html

… and the chair on the right is the peerless “Egg” chair, by the Dane Arne Jacobsen: still in production and a classic of mid-20th century design.

…. well, and what does that say about mid-20C?

Fortunately, there are still manufacturers who keep older styles of design intact, and there is a market for it:

http://azraves.com/interior-designers-boston/interior-designers-boston-on-interior-with-popular-interior-designers-property/

(Although you have to be a conductor to be able to afford it.)

There’s two new produtcions of Martinu works at Oper Frankfurt in June/July.

And Hartmann has never entirely disappeared from the programmes, at least in Germany.

Poulenc, Messiaen, Bernstein, Shostakovich, Britten… And I’d also make the case for Martinu.

I don’t think you can include Martinu in that category. His stuff is programmed much more than the others you mentioned.

Musically, the last half of the century has less appeal; it is cerebral. Therefore fewer people will be interested. Exceptions operatically include people like Carlisle Floyd.

The reason is simple. The most creative American musical talents of the post-war era composed popular music, jazz, musicals, film scores etc., not symphonies or chamber music. But Bernstein and Copland are still performed, and couldn’t Kurt Weill be considered an American composer?

But is this anything new? The history of classical music is littered with these dead ends. Perhaps the difference over the last 150 years is that a creative class evolved among bourgeois societies that tended toward forms of cronyism that allowed for the promotion of mediocrity amplified by cultural nationalism. Even a group like the Boston Six (Amy Beach, George Chadwick, Arthur Foote, Edward MacDowell, John Knowles Paine and Horatio Parker,) which existed in the very earliest days of modernism, and whose music was rather approachable, was high in status during their lives but soon forgotten:

Something similar happened as nationalism weakened and was replaced by large trans-national political ideologies. Social Realism became the ideal of the East, and an individualistic, apolitical Modernism the ideal of the West. The American government even intervened with massive secret programs to turn the Western intelligentsia away from socially themed art toward the more apolitical forms of modernism. This might help explain why the Northeastern establishment’s modernist complexity became very powerful, but as the Cold War faded, it went through one of the most precipitous collapses in the history of music – as if the stage of history had a trap door. We saw that art cannot be defined by ideological constructs. Much of the artifice of American Postmodernism will likely die the same quick death, as will the ongoing Modernism of the European scene, but as always, the ideologues have the power.

That’s why we have now the ideological vacuum, the end of the ‘grands récits’. Given the enduring presence of the past in terms of repertoire, a past which is continuously uncovered, a static situation has developed within which there is place for different musical traditions next to each other, all competing for audiences’ and performers’ attention. This gives the opportunity for the artistically-substantial to make its mark.

Leonard B. Meyer has predicted this state of affairs already in his ‘Music, the Arts, and Ideas’ of 1967 (!!!).

Great art has, of course, evolved out the metanarratives of history (feudalism, capitalism, communism, Catholicism, etc.), but we now live in a world of distrust for such ideals. They are seen as unable to account for the chaos, heterogeneity, and locality of the world humans actually live in. ‘Grands récits’ = Grand deceits. Great art seems to appear exactly because it somehow transcends the limitations of metanarratives.

Since the disorder of the universe makes metanarratives untrustworthy, we try to find understanding through a multiplicity of standpoints. That which is legitimate can only be local, so to avoid parochialism we develop a detached and ironic nihilism that becomes a form of liberation. Then we quickly discover that believing in nothing is also a confining metanarrative, but there is no belief left as a solution.

Time is also a form of locality, because belief systems are always transitory. From this perspective, art becomes a kind of a monument to human folly. We look at the accomplishments of the past, the pyramids, the cathedrals, with a sense of pity and marvel, as with those vanishing mid-modernists under discussion.

As Wittgenstein might have put it, all art and knowledge become ephemeral language-games vanishing in time. Under this metanarrative, the ideal of eternal meaning in art is lost. History dissolves under our feet. In a universe with no center, we watch as Radiohead becomes equal to Beethoven. We wonder if there was ever a reason to believe in Piston, Sessions, and Harris in the first place. The idea of which composers might remain becomes irrelevant, because there’s nothing to believe in at all. We live in Alice’s fleeting world where we have little choice but to just make up everything as we go along, only to watch it vanish.

An excellent specimen of postmodern observation. I only take offence at the repeated ‘we’, since – for good reasons – not ALL people with some intellectual experience think this way, it is a tired Weltanschauung of intellectuals who florished in the 2nd half of the last century, who now see their worldview crumbling. But on the other hand, there is indeed much crumbling – and in that sense, I agree with mr Osborne (I must be ill!).

“We look at the accomplishments of the past, the pyramids, the cathedrals, with a sense of pity and marvel, as with those vanishing mid-modernists under discussion.” If with ‘pity’ is meant: ‘regret’, this would be an apt observation. But since Nature renews itself again and again, we can also hope for new generations who get back on their feet and see the accomplishments of the past as a meaningful human endeavor – since those poor innocent artists of past times, who had no idea about the postmodernist self-deconstruction that was to undermine all receptive frameworks, address general life experience.

A short look into the Louvre, National Gallery, the Uffizi, or the Royal Opera House, the Vienna Staatsoper or Musikverein or Berlin Philharmonie on a performance night, would reveal a lively and fascinated audience flocking to works of art which have developed an exaggerated iconic status. Postmodern deconstructuralists will not be found there because they are gloomly sipping their port at the hearth, with all the books about the Untergang des Abendlandes in their back, weeping about the lost culture of the West.

No pity for the pointless slave labor that created the pyramids, or the totalizing forms of Christianity represented by the cathedrals that crushed so much humanistic thought?

Let’s add Howard Hanson to this stellar list. He was not only the foremost leader of the Eastman School of Music for 40 years after Kodak founder George Eastman saw him conduct his First Symphony, his other symphonies and in particular, a terrific Piano Concerto from 1948, should be performed more. (The Piano Concerto was premiered by Rudolf Firkusny and the Boston Symphony, and Eugene List performed it with the MIT Orchestra, as well as Carol Rosenberger’s fine recording with the Seattle Symphony in later years).

While lovely to listen to, the Hanson piano concerto is actually quite boring to play. Much of it is more “student concerto” than mature work – both musically, and technically (for the performer).

There are other far greater concertante works for piano and orchestra by American composers from the same decades that deserve more exposure.

Perhaps this concerto needs a revival and a cracker-jack energetic performance. It is far from boring imho and has a rhythmic visceral energy which is quite exciting with the right touch and rhythmic drive. The slow movement could be perceived as boring, but it has to be done in the right hands with a keen sense of forward motion and feeling and wide range of dynamics. [Another mid-century composer, Leroy Anderson, offers a wonderful piano concerto which is inventive and great fun. You have probably heard of it.]

Article on the subject by Leonard Slatkin: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/leonard-slatkin/where-did-our-musical-leg_b_4986013.html

I remember this article. It is terrific. Perhaps conductors will heed Maestro Slatkin’s advice and find a niche for themselves with repertoire that suits them and has something interesting and unique to offer to today’s audiences.

Martinu is definitely on the upswing. In recent years, I’ve seen a bit more Piston and Schuman on concert programs. I hope this trend continues.

There may be observed a need in concert programming for new works which do not disrupt the context of the perfomance culture.

Malcolm Arnold hasn’t been dead for a generation by any means. And beyond the BBC, where the unwritten blacklist is still very much in force, his smaller-scale music is still getting a lot of performances, both amateur and professional.

The issue, of course – as with so many post-war tonal composers – is the larger-scale music: symphonies in particular. There are very few orchestral concert promoters who can risk devoting the full second half of a concert (and symphonies are still essentially “second half works”) to anything that’s not particularly familiar, however attractive. And that’s a problem with repertoire stretching back to the late 19th century: it’s why we don’t hear symphonies by Balakirev, Franz Schmidt, Roussel, Stenhammar, Ives, Bax and so many more.

Visit the world of wind band music. Many of these composers–and I’m thinking of Persichetti in particular–are staples of our concerts. I have conducted the works of Piston (his one composition for the medium), Schuman, Arnold (a large number of his works have been transcribed, and others. For what it’s worth, with orchestra I led a concert including Chadwick’s Jubilee in Russia a number of years ago. It was the “hit” of the show!

The advantage of many midcentury composers is that they are understandable, they not yet being infected by the missionary dogmatism of Darmstadt and Boulez.

“Concerto funebre” by Hartmann or “Polyptyque” by Frank Martin are surely as gripping and breathtaking as music can get, same can be said for many works of Ginastera (e.g. Concerto for strings) or Sandor Veress (e.g. Musica concertante for 12 Strings).

We will come back to them after having been exhausted by Bruch, Dvorak, Glazunov and the ever same Baroque pieces….

Norman, could you organize a public debate between Messrs Borstlap and Osborne?

Is this not public enough? And then, I would be very worried that Mr Osborne would not wear a tie.

I think I have one here somewhere….

Martinu is certainly performed more than Babbitt, or Boulez, or Carter. The latter, which represents a certain aspect of Modernism, you can hear on recording – but not much in person. Many composers of mid-20th century are alive and well: Barber, Lutoslawski, Bernstein, Ligeti. Those composers who didn’t care much about the audience (unlike Mozart), just aren’t heard much.

I am amazed at the speed with which the discussion occasioned by my remark plunged into the deepest possible questioning of contemporary culture. Delighted, too, of course. The whole article (thanks to my daughter) is available on the website http://www.parallelmusicstudios.com (under “writings”) for anyone interested. Meanwhile, a word about mid-century modern furniture. The style had an ethical basis — it used plywood and steel, industrial materials suitable for mass production — and an ethical heritage — William Morris, Arts and Crafts, Bauhaus — with the thought that good design should be available to the average person. The way things worked out, the average person did not find the modernist style appealing, and the furniture by and large ended up in wealthy homes. So in practical terms it was a failure. But maybe just that impulse — the desire to make something beautiful for the average joe — was enough to lift it out of the ordinary and give it its sustained life.