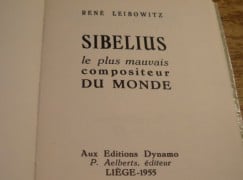

‘The worst composer in the world’ (by Boulez’s teacher)

mainOur colleague Lotta Emanuelsson of YLE has come across this scarce 90th birthday biography of Jean Sibelius.

It is the work of René Leibowitz (1913-1972), Warsaw born and student of Webern, who converted post-War Paris to the creed of serialism. His star pupil was Pierre Boulez.

Comments