Why London can’t be bothered to commemorate composers

mainCampaigners for a plaque to mark Haydn’s two visits and 12 symphonies in London have been recycling one of the last pieces I wrote as assistant editor of the former Evening Standard, before it was sold to a KGB man.

Rereading the piece, I think the original premise still holds – that London is too busy making music to memorialise it – but I am struck at how much the stellar voltage has dropped over the past five years in the city’s main music venues.

In 2014, there are far fewer limelight events than there were in 2009. Are we heading for a double-dip musical recession?

Here’s the piece:

Every year around this time London makes an all-out assault to be crowned as musical capital of the world. The BBC Proms are announced, bigger than before. The Southbank Centre brings out its trophy orchestra, the Simón Bolívar of Venezuela, with the electrifying Gustavo Dudamel. The Barbican bites back with the infinitely popular Lang Lang. Covent Garden goes into Wagner mode and the Coliseum goes experimental with Purcell. No city on earth has more nightly performances than London and none can approach its depth and diversity.

Yet, in the premier league of music capitals, London struggles for recognition beside Vienna, Paris and Milan. It is regarded as a bit of a parvenu, a place of skimpy traditions, capital of what Germans used to call the Land Without Music. None of the three Bs — Bach Beethoven, Brahms — ever set foot on British soil and no symphonic genius was born on the banks of the Thames.

London lacks the history, the opus numbers and well-trod tourist trail to match the legends of European heritage. These prejudices are inarguable, yet the premise on which they are founded wilfully distorts the unique place that London occupies in the evolution of western music.

So what if we had no three Bs? Bach’s brightest son, Johann Christian, lived and composed here for 20 years and London commissioned Beethoven to write his ninth symphony. Every other musical genius has spent formative time in London — Mozart, Verdi, Chopin, Berlioz, Liszt, Wagner, Tchaikovsky, Mahler, Bartók, Schoenberg, Gershwin, Janacek and Ravel, down to the age of budget flights. Gounod took asylum here from the Franco-Prussian War, Nikolai Medtner from the Russian Revolution, Roberto Gerhard from Spanish fascism and Andrzej Panufnik from Polish Stalinism.

For more than three centuries, London has been the world’s clearing house for musical ideas, a refuge for displaced talent and the prototype of a viable arts economy. Classical music’s most appealing image is a packed Royal Albert Hall at the Proms; the most visited shrine is the street wall of Abbey Road studios; and wherever the next wave is going to break it won’t be in Vienna, Paris or Milan.

London is forever in a state of renewal, adding new venues and refurbishing the old. In the past two decades it has spent half a billion pounds on Covent Garden, the Coliseum, Southbank, Barbican, Kings Place, Conway Hall, Sadler’s Wells, Wigmore Hall and more. What it cannot be bothered to do is look back on past laurels and polish them up for the tourist trade. It goes against the grain in our culture to brag of past pomp and circumstance, and music, for some reason, is shyer than other arts in parading its glories.

While every potboiler of Victorian fiction, every sub-Turner landscapist, gets a blue plaque on a street wall, the makers of musical London make do with a small bust in a concert foyer or cathedral, often so high up as to be invisible.

Researching composers in London is like prospecting for gold at a busy intersection. You either strike lucky within minutes or get dragged off in a straitjacket. It is impossible, for instance, to locate where Henry Purcell was born in 1659, or any of the four Westminster houses he occupied. All that endures is a grave in the Abbey and a bust off Victoria Street, erected so recently (1995) that its existence is more a national embarrassment than a memorial.

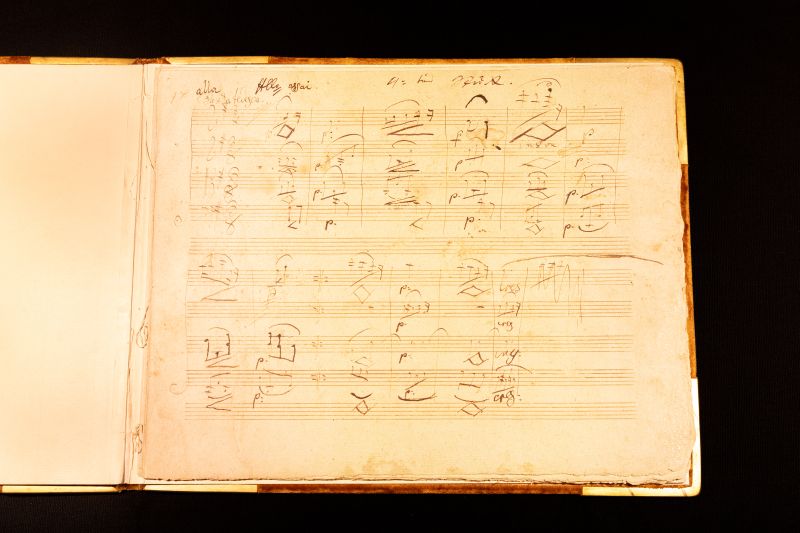

Of the composers also celebrating anniversaries this year, Haydn’s London was razed by developers or bombed by the Luftwaffe. Hanover Square, where he presented the 12 London symphonies in the early 1790s, is an unsightly tangle of offices around a day-long gridlock. The Pantheon on Oxford Street, where his cantata Arianna a Naxos was sung, is a branch of Marks & Spencer. Haydn’s clavichord can be seen, by appointment, at the Royal College of Music.

Mendelssohn, who also played the Hanover Square Rooms, spent time in the suburbs in 1829 after being “thrown out of a cabriolet and very severely wounded in the leg” on Beulah Hill, in Norwood, “famous for its good air”. He was laid up for four days and wrote a little piece titled The Evening Bell, echoing the chimes of a nearby church. The house where he stayed, and the church, were demolished in the 1960s.

Handel, who came to London in 1712 at the age of 27 and lived here until his death on 14 April 1759, has left the most visible legacy. His combustible, manic-depressive personality matched Samuel Johnson’s for gossip fodder and his gargantuan appetites for food and work were liberally caricatured. Handel has a monument in Westminster Abbey and the last of his residences on Brook Street was turned eight years ago into the Handel House Museum, a quaint anomaly beside the designer dens of Bond Street.

The spirit of Handel is to be found in unlikelier places. After Queen Anne’s death in 1714, the composer retreated to the Duke of Chandos’s estate at Stanmore, commuting into town along what is now the Edgware Road. Even as a young man, Handel could not go anywhere unrecognised and his progress was recorded in local histories, prompting developers to put little busts of him into new buildings along the route. One such cast can still be seen above what was, until the present crunch, a branch of Woolworth’s in Kilburn High Road.

This is as close as London gets to putting musical genius on a pedestal and I have stood there often, among milling shoppers, admiring Handel’s posterity. To find his soul, I go to St George’s Church, just below Hanover Square where, up to the last Sundays of his life, Handel would play the organ so irresistibly that the congregation would beg him to stop so they could get home to lunch. Handel, here, belonged to the rhythms of London, the unchangeable habits of centuries, the furniture of our lives.

London does not commemorate composers as other cities because we have assimilated them into our contemporary reality, recycled them into a dynamic culture. London as a musical capital is unique in its casual assumption of past glories, its absence of fake nostalgia, its eye on the next genius to come. Music in London is not about yesterday. It’s about tomorrow.

(c) NL, April 2009

Mysteriously my posting about Mendelssohn’s blue plaque in London has disappeared?

But here is the detail confirmed by an independent source:

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/about/news/blue-plaque-for-mendelssohn/