Abbado and America: a mismatch

mainThe great Italian maestro, whose death was announced today, was principal guest conductor in Chicago from 1982 to 1986. Solti looked upon him as a likely successor but the cards never fell that way, nor did subsequent interest from the New York Philharmonic lead Abbado to take up what America regarded as the summit of a conductor’s career – music director of a Big Five orchestra.

Abbado was managed by Ronald Wilford at CAMI but never showed the requisite ambition. Wilford reacted with astonishment when the Berlin Philharmonic players elected Abbado as Karajan’s successor (he had been pushing James Levine). In the music business, Abbado was often talked of as a maverick. What managers failed to understand was his fundamental idealism.

Abbado, the son of anti-Fascist resistants, was politically on the Left. He had friends in the Italian Communist Party and was no fan of the market economy. Not short of ego, he disdained the commercial trappings of celebrity and refused to promote his many recordings with media appearances. He was a misfit in America, a man who gave nothing away to the myth-making industry, preserving his integrity and thereby missing every available opportunity. He showed no sign of regret.

UPDATE: Andrew Patner has more here on Abbado and Chicago.

It goes without saying, this is a huge loss. R.I.P.

Great sadness but also great gratitude for all the wonderful performances. I remember the Vienna and Berlin Phis and the LSO where I heard him and once or twice had the privilege of broadcasting his concerts. But most of all a single Salzburg concert with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe and Brendel in Mozart and Mendelssohn . The intimacy between Abbado and his young players was musical conversation as its most perfect. Mille grazie.

In 2007 Maestro Abbado conducted a joint performance of his Mahler Chamber Orchestra and Simon Bolivar Orchestra. After a marvelous version of Brahms’ 3rd Symphony, there was a dinner event of both orchestras. Maestro Jose Antonio Abreu graciously invited me to sit at their table, and I had the privilege to talk with Maestro Abbado for an hour or so. I told him my first recording of him was a 1970 or so LP with Boston Symphony, a Debussy-Ravel issue. He then told me he was shocked the first time he rehearsed with the BSO organisation, because during intermission he departed with a couple of musicians on the music they were preparing, only to be approached by the orchestra staff manager, who told him it was forbidden for guest conductors to talk with musicians during rehearsal breaks.

Claudio Abbado came to NY with the Berlin Phil shortly after 9/11. Changing his programme from Mahler to all Beethoven, they gave Toscaninian fiery performances, the 4 basses making more tone than the usual 8 from most other orchestras. These performances said many things, and they came as wonderful salve to a city with a damaged psyche. I heard him in Berlin last year (Schumann 2) and it was wonderful. He will be missed and his recordings cherished.

I too remember the post-9/11 Carnegie concert. The audience roared with gratitude that the Berliners had decided to come despite the unbelievable anxiety. I have never since heard such cheering, it was laced with primal fear. Rudy Giuliani, still in his Finest Hour, introduced him, which was an experience in itself…..it’s too bad about the NY Phil, though. It would have been wonderful.

Abbado and the New York Philharmonic were a signed contract away from his succeeding his good friend, Zubin Mehta, as the orchestra’s next Music Director—there had been a handshake agreement. Then came a call from Berlin……

If you happen to be the real Martin Bookspan, then I apologize.

That’s the name on my birth certificate. Is there another Martin Bookspan?

I’m sure there are. It’s the Internet.

I rather doubt though that Abbado seriously contemplated taking that job – after all, as you mentioned, he and Zubin Mehta were very good friends. And Mehta didn’t fare too well as MD of the NYP. He no doubt came in expecting it to be, as Norman put it, the “summit of a conductor’s career – music director of a Big Five orchestra”. The summit of *his* career. But things didn’t go very well at all for him there. And the orchestra, at least back then, was known to pride itself in giving conductors a particularly hard time.

Whatever really happened, Abbado must have heard all about it from Mehta, and I can’t see somebody as introvert and non-confrontational as Abbado stepping gladly into a situation like this.

And, although he and Muti reportedly didn’t get along well, it can’t have escaped him either that his fellow Italian was also not doing too well in Philadelphia at the same time. And, predictably, another friend of his, Barenboim, also had a lot of problems in Chicago although that was slightly later.

I can’t see Abbado being too keen on dealing with that typical American attitude of “we are the greatest orchestras in the world so who are *you* to conduct us, to tell us to do things differently from how we have always done them”.

In Berlin, on the other hand, he was *expected* by the majority of the orchestra to bring about change, to let some fresh air in. Their attitude was “we have acquired that legendary reputation with Karajan, but that era is now over, we can’t rest on that forever, and it is time for a new approach”. Which is why they elected Abbado and not one of the, at least in their own mind, more “obvious” candidates who were more likely to just go on doing things the way they had always been done.

Abbado was interested in a U.S. position, that was never a secret. He conducted regularly with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for 20 years — 1971 through 1991 — and was a very busy principal guest conductor for three seasons, 1982-1985, including domestic tours and Carnegie Hall appearances, not to mention his active recording program. He was one of only two candidates to succeed Solti in 1989. The other was Barenboim who won out. He had serious talks with New York. When the Berlin post materialized, he wound down his work with U.S. orchestras. Each position he held or sought was individual and each — Scala, Vienna, London, Berlin, Chicago — presented its own ups and downs for him. The issues were not “American” or “European” — he left posts in the U.S., Italy, the UK, Austria, and Germany for his own reasons and ultimately established orchestras that were run on his own terms.

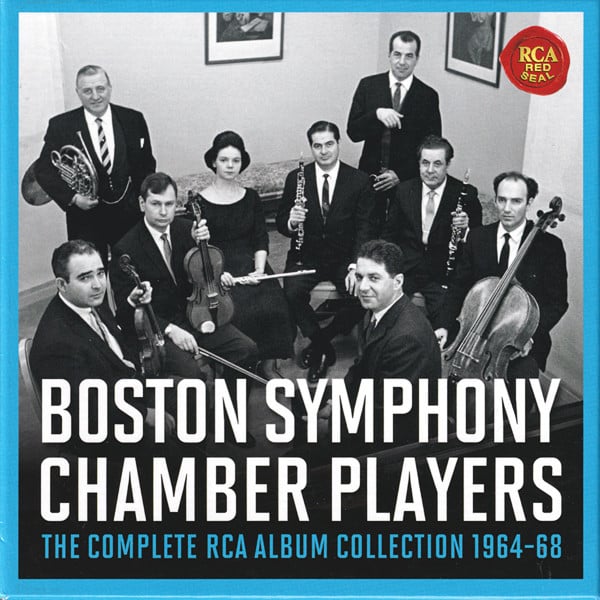

Early in his career Abbado was given an enormous boost by two of the “big 5” American orchestras, the Boston Symphony and the New York Philharmonic. As a result of winning the Mitropoulos Conducting Competition Abbado served as an Assistant Conductor of the Philharmonic for a year (that photo of Bernstein and Abbado derives from that period). And after winning the Koussevitzky conducting prize at the Boston Symphony’s Tanglewood, Abbado was invited to conduct the BSO—and he even recorded with them (the Debussy Nocturnes are still available on CD). And as Andrew Patner points out, Abbado had a very substantial and productive association with the Chicago Symphony.

Claudio Abbado was a great musician and a kind person as well. I sent a young conductor to meet him in Berlin, about 20 years ago, and Claudio invited him to attend his rehearsals.

I had sent a cassette of New York Philharmonic musicians’ memories of Mahler to him. He wrote me a beautiful thank you note, and said that he would be happy to listen to any bassist I sent to audition for him for his European Youth Orchestra. We knew he had been invited to be our Music Director at the Philharmonic, and realized that his acceptance of the offer from Berlin would mean that he could still continue in Vienna. Who could resist such a combination?

“…he said that he would be happy to listen to any bassist I sent to audition for him for his European Youth Orchestra”

…except you actually have to be a citizen of an EU member country to be accepted into the EUYO, or ECYO as it was called back then.

Thank you, Norman! The Chicago piece can also be accessed directly here: http://viewfromhere.typepad.com/the_view_from_here/2014/01/claudio-abbado-1933-2014-elegant-passionate-focused-generous-my-chicago-sun-times-obituary.html