Why is London’s National Gallery showing stolen art?

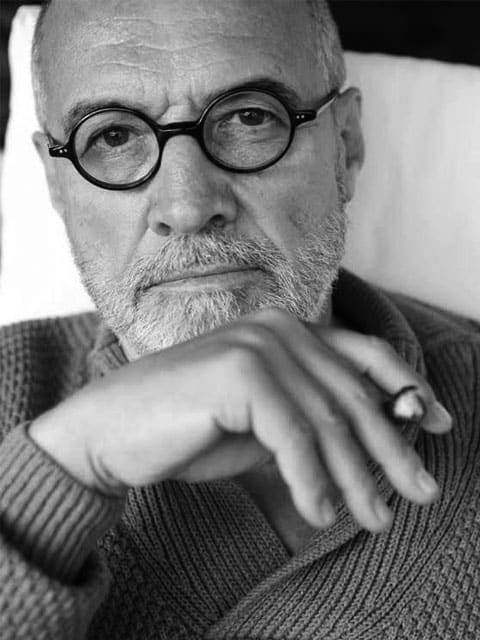

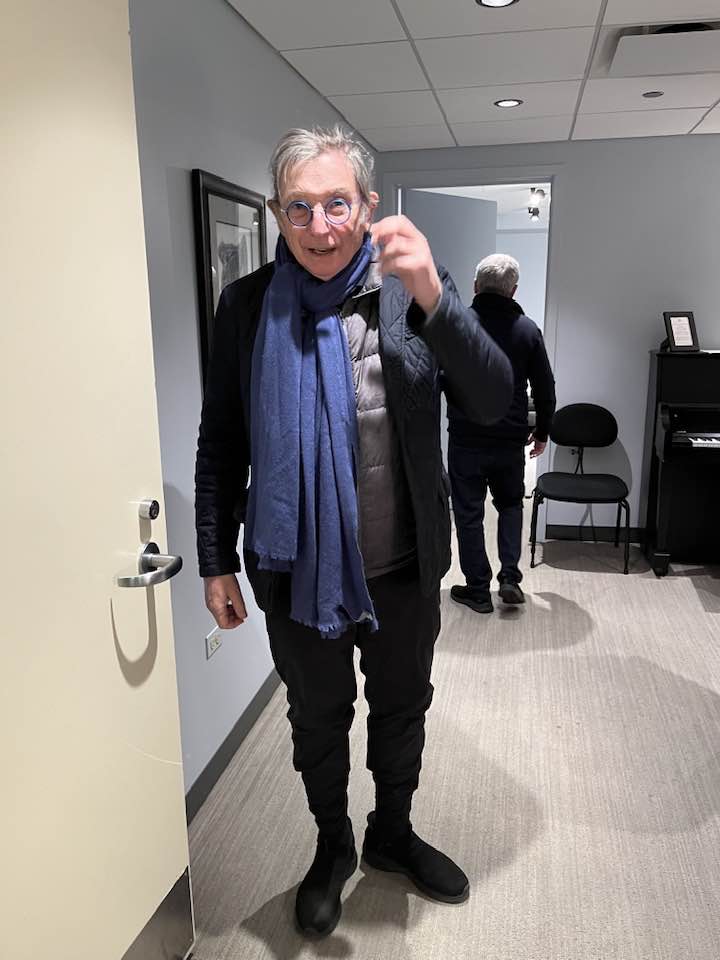

mainE. Randol Schoenberg, grandson of the great composer and a lawyer specialising in restitution of art stolen by the Nazis, has drawn our attention to a Klimt portrait in the current National Gallery show, “Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900.”.

The portrait is of Amalie Zuckerkandl, member of a newspaper family with whom Gustav Mahler was notably friendly. It was given by Amalie to her friend, Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, another Mahler acquaintance, and was stolen from him by the Nazis when he was forced to flee Austria in 1938.

The Austrian authorities have refused claims to return it to the legitimate owners. Randol Schoenberg has posted the family’s case for restitution here. It’s a powerful case. The National Gallery should search its conscience.

“The National Gallery should search its conscience”

The National Gallery, alas, is hardly unique in this.

Indeed. Depending on one’s definition of “stolen”, a great deal of the art in many of the world’s great museums is stolen, including some of their most famous assets, e.g. the Elgin marbles in the British Museum which were ripped off the Parthenon in Athens.

I just read a good book about this subject: “Loot: The Battle over the Stolen Treasures of the Ancient World” by Sharon Waxman.

An unfortunate aspect of the Elgin Marbles dispute is wilful distortion of the circumstances of their acquisition. Emotive phrases like “ripped off” is an example.

There’s no doubt that attitudes have changed over 200 years and many of the world’s institutions should probably be reviewing their collections, including other museums holding sculptures from the Parthenon. However, ignoring the dire condition of the rest of the Parthenon, and the graceless approach by some representatives the Greek position, are not constructive.

You are right, saying that the marbles were “ripped off” is a distortion of what really happened; they weren’t ripped off, they were hacked and sawed off.

The British Museum is also sitting on Nazi loot:

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/may/27/arts.parthenon

Elgin’s argument was that he had permission from the Ottoman rulers of Greece in the late 1790s. That’s arguable, as is the point that he saved them from subsequent damage (though the early 19th century cleaning methods of the National Gallery destroyed a lot of the surface texture and possibly some pigment). What’s more certain is that if we return them, the West’s museums will empty…

Why? Why would returning one piece (or in this case, one set) of art mean that “the West’s museums will empty”?

Some say that is because it would “set a precedent”. Which I suppose is also why the Austrian gallery doesn’t want to return this painting. But I think that is the wrong attitude in both (or all similar) cases. They should be decided on a case-by-case basis. If it came down to “conscience”, then yes, I guess that would mean the National Gallery, the British Museum and many other museums in other countries as well would be nearly empty soon.

Under the circumstances, is it not perhaps surprising that the painting was sent on loan out of Austria?

The National Gallery should at the very least add a paragraph on the ownership controversy to the walltext beside the painting. A feeble gesture is sometimes better than none at all.

Well, I really can’t see why the National Gallery should search its conscience. The so called legitimate owners lost their case in front of an arbitration panel; their appeal was thrown out by the court of appeal of Vienna, then by the Austrian supreme court. These are possibly poor judgments, it happens, but the question of the property of the picture has been settled by the independant courts of a democratic country.

And, by the way, taking the side of one party in that dispute without having heard the arguments of the other one strikes me, to say the least, as unfair.

Galleries don’t have consciences; they have collections.

One can only hope that Schoenberg will be as successful as he was in the case that went all the way to the U.S, Supreme Court, in which Maria Altmann (née Bloch, later Bloch-Bauer) gained back several Klimt paintings that the Austrian government had likewise refused to return.

This seems to be an ongoing issue–espec. art allegedly stolen by the Nazis. I think Julien above has a good point. Who actually owns what? Sometimes, it’s not always so clear. One can lay claim to anything. But proving it is another story. If Julien is correct, the National Gallery has nothing to clarify or for which to apologize.

There’s a line from A Question of Attribution by Alan Bennett where Anthony Blunt says: “There is no such thing as a Royal Collection; it is more a Royal Accumulation.” Not realising he is overheard by the Queen, she pipes up. “And how did we “accumulate” this particular picture, Sir Anthony?”.

What an exquisite portrait. It belongs in the family of its rightful owners.