Is France rejecting the Boulez line for the Bacri solution?

mainAnalysis by John Borstlap:

On April 27, the French Radio Orchestra presented a concert entirely dedicated to a French composer who began his career within the established modernism, where Pierre Boulez was arbiter of taste and executive of a ‘party line’.

Bacri’s first works were modernist, dense in ideas, and filled to the brim with dissonance as was custom at the time – until he encountered the works of Giacinto Scelsi. Bacri met the eccentric composer in Italy while spending – in the early eighties – his obligatory period at the French Academy in Rome after winning his Premier Prix. The works of Scelsi, being the extreme opposite of Bacri’s in its concentration on a minimum of material (often merely one tone with microtone oscillations), made Bacri realize that a wealth of extreme material is not necessarily saying more that a single, concentrated tone that has enough of itself.

Scelsi’s minimalist works acted like a pin, puncturing the modernist balloon in Bacri’s mind. He came to understand the reason of the timelessness of the great music which already exists and has been able to bridge vast spaces of time and place, and still forming the repertoire of classical music today, alive and kicking in spite of the critique from socialist and populist quarters. From then on, Bacri began to explore tradition, without surrendering to compromise or imitation.

This fell beyond the scope of established new music in France, with the result that Bacri found himself outside the establishment. But with the withering of modernist ideals in recent years, Bacri’s music has got increasingly performed and began to be understood as a viable way out of stagnating modernism. In this he was not alone: Karol Beffa, Richard Dubugnon and Guillaume Connesson are, like Bacri, trying to find alternative ways of looking at new music and of finding stimulating perspectives away from the mental prison that new music in France had become.

So, this concert at Radio France is, in fact, a spectacular confirmation of the place new tonal music has acquired in the heart of the French musical establishment, and it celebrates Bacri as one of its most gifted and muscially profound composers. In 2012 a lecture at the Collège de France by the pianist Jerome Ducros criticising atonal modernism, drew a flood of furious, hateful condemnations from the modernist establishment. The ‘affaire Ducros’ created a flow of articles pro and contra that ran in the media until 2015. But this Bacri concert by the French radio orchestra seals the end of the Boulez domination …. and opens-up a perspective of hope for new music as an organic part of the normal, regular performance culture.

The concert can be heard on this link:

Bacri’s music is not ‘conservative’ because of its interpretation of traditional values, because his interpretations are always personal, expressive and authentic, using a familiar-sounding musical language but what is ‘said’, is always new. Basically, it is a return to normal practice of how a musical tradition functions. As John Allison wrote in The Times: “Bacri is a composer capable of renewing an old-fashioned medium.” But Bacri does not discard the idea of modernism altogether, there is in his music a certain tension breaking-through the harmonous surface and creating moments of ambiguity and instability, with unexpected and subtle surprises. Bacri wrote two very interesting booklets, in which he describes his artistic development and how he came to find a new understanding of the tonal tradition: “Notes étrangères” and “Crise (notes étrangères II)” – unfortunately as yet not available in English.

As he said himself: “My music is not neo-Classical, it is Classical, for it retains the timeless aspect of Classicism : the rigour of expression. My music is not neo-Romantic, it is Romantic, for it retains the timeless aspect of Romanticism : the density of expression. My music is Modern, for it retains the timeless aspect of Modernism : the broadening of the field of expression. My music is Postmodern, for it retains the timeless aspect of Postmodernism : the mixture of techniques of expression.”

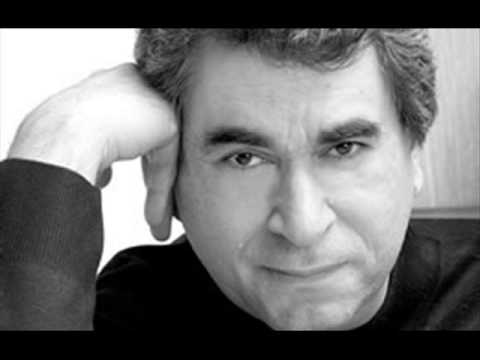

Photo (c) Thierry Martinot / Lebrecht Music&Arts

Comments