Is this Liszt’s lost opera? Have an exclusive listen…

mainThe title is a tongue-twister – Sardanapalus – based on a Byron play.

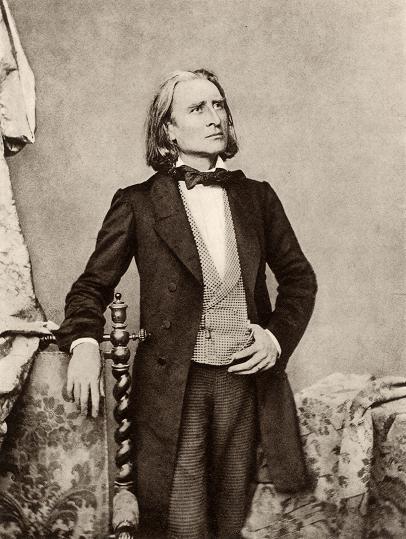

Liszt worked on the opera in 1849-5o, after he gave up touring as a piano virtuoso and settled in Weimar.

He finished only one act, which was never performed. A Cambridge academic, David Trippett, has found the manuscript in Weimar and prepared it for a premiere this summer.

You can hear an exclusive aria here.

And watch a background report:

press release:

An Italian opera by Franz Liszt – left incomplete and largely forgotten in a German archive for nearly two centuries – will be given its world premiere this summer after being resurrected by a Cambridge academic.

David Trippett, Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Music at the University of Cambridge, first discovered the opera languishing in an archive in Weimar more than ten years ago. Known only to a handful of Liszt scholars, the manuscript – with much of its music written in shorthand and only one act completed – was assumed to be fragmentary, often illegible and consequently indecipherable.

However, after Trippett spent the last 2 years working critically on the manuscript, a ten-minute preview will now be performed for the first time in public as part of the BBC Cardiff Singer of the World contest in June.

“In 1849 Liszt began composing an Italian opera, but he abandoned it halfway through and the music he completed has lain silently in an archive for nearly 170 years,” said Trippett. “This project is about bringing it to life for the very first time.”

“The music that survives is breath-taking – a unique blend of Italianate lyricism and harmonic innovation. There is nothing else quite like it in the operatic world. It is suffused with Liszt’s characteristically mellifluous musical language, but was written at a time that he was first discovering Wagner’s operas.

“The only source for this opera is a single manuscript containing 111 pages of music for piano and voices. It was always assumed to be impossible to piece together, but after examining the notation in detail, it became clear Liszt had notated all the cardinal elements for act 1. You have to think through the artistic decisions traceable in the manuscript and try to reconstruct the creative process, to see how Liszt’s mind went this way and that.”

A critical edition of the music for act 1 will be published by Editio Musica Budapest (Universal Music Publishing) in 2018. Although Trippett has worked alone on rescuing the music Liszt notated, Cambridge’s Francesca Vella has worked on deciphering the Italian text alongside musicologist David Rosen, whose principal role has been to translate the libretto into English.

The libretto, based on Lord Byron’s tragedy Sardanapalus, tells the story of Sardanapalo, King of Assyria, a peace-loving monarch, more interested in revelry and women than politics and war. He deplores violence and brutality, and, perhaps naively, he believes in the innate goodness of humankind, but is overthrown by rebels and burns himself alive with his lover, Mirra, amid scents and spices in a great inferno.

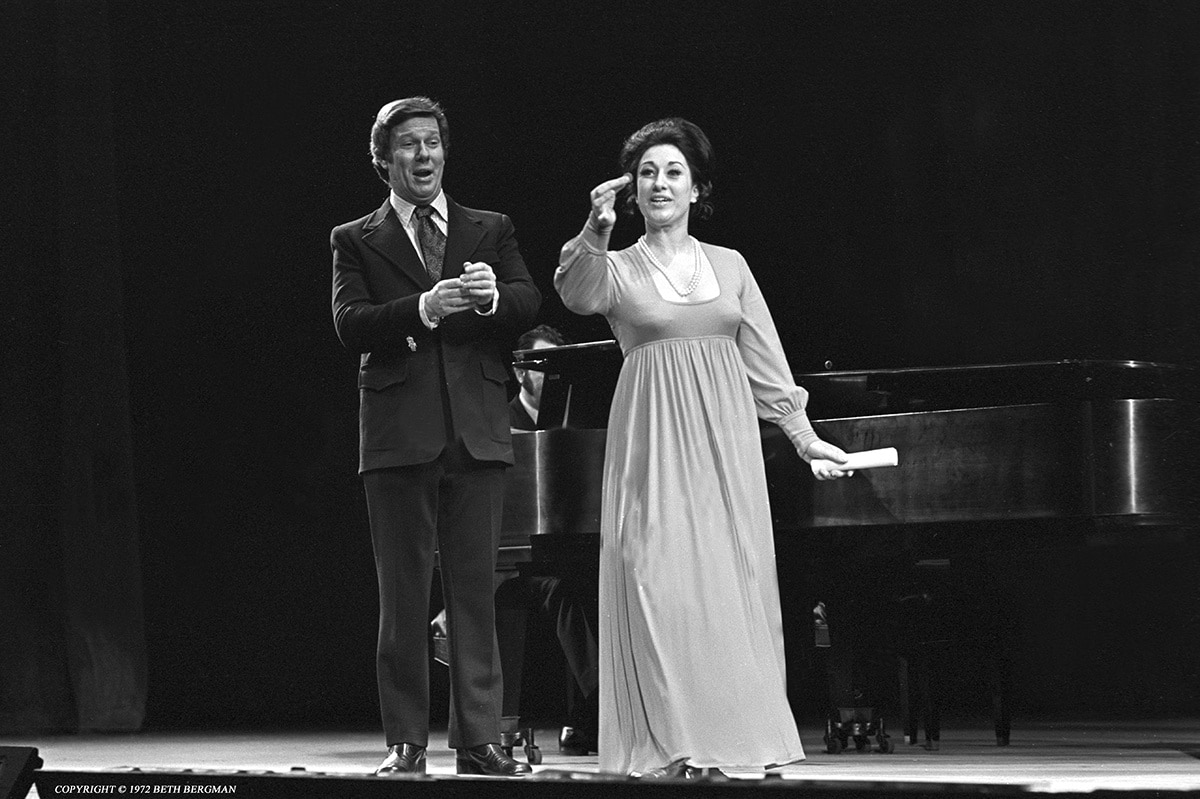

A ten-minute scene from the opera will be performed at the final of the BBC Singer of the World event by Armenian soprano and rising talent Anush Hovhannisyan.

“In effect, the manuscript has been hiding in plain sight for well over 100 years,” added Trippett. “It was written for Liszt’s eyes only, and has various types of musical shorthand, with spatial gaps in the manuscript. A lot of it is very hard to read, but the scruffiness is deceptive. It seems Liszt worked out all the music in his head before he put pen to paper, and to retrieve this music, I’ve had to try and put myself into the mind of a 19th-century composer, a rare challenge and a remarkable opportunity.

“Fortunately, Liszt left just enough information to retrieve what was evidently the continuous musical conception he had at the time. We will never know exactly why he abandoned his work on the opera and I suspect he would have been surprised to learn that it is resurfacing in the 21st century. But I like to think he would have smiled on it.”

Ahead of the BBC event in June, Trippett and his colleagues are putting the finishing touches to a documentary film for the University of Cambridge chronicling the resurrection of Liszt’s forgotten masterpiece, with singers Anush Hovhannisyan (soprano), Samuel Sakker (tenor) and Arshak Kuzikyan (bass-baritone). This will be released on 15 May.

“Who else gets to premiere a new opera by a superstar composer from two centuries ago?” said soprano Hovhannisyan. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and the entire process of making it work – from thinking about the character and what Liszt would want – has been a privilege. We have had a wonderful, deeply creative and imaginative time piecing this together and I feel very blessed to have been a part of it.”

What a fantastic project, and judging by the beautifully performed extracts on the video clips, this is top-drawer Liszt. I am really looking forward to hearing more of it on Cardiff Singer of the World!

Amazing. I’m always sceptical about these kind of things but this has a real air of authenticity to it. Great music.

Fully agreed! What a genuine loss that he never saw it through.

Liszt’s opera/oratorio The Legend of St. Elizabeth (1857-62) is absolutely marvellous and should be revived too

Great project. What can be heard in the video, is very enthusiastic music à la Italian opera but with a different flavour added to it. When Liszt began to understand the scope and level of Wagner’s talent, that must have been the reason he abandoned the piece. And later-on, his creation of the ‘symohonic poems’ offered him a space, independent from Wagner’s opera’s with which he must have felt incapable of competing with.

It sounds marvellous as sung here and would be even more fascinating if orchestrated. Would the reason for Liszt abandoning the work be his discovery of Wagner? Possibly he thought he couldn’t match Wagner’s ideas and ideals, and/or he then devoted his time to championing the other composer’s work with characteristic altruism and generosity.

There is some foul play here. Mr Trippett didn’t exactly ‘discover’ the manuscript. The only source of the opera – sketchbook MS N4 (111 pages for Sardanapale, among other things), which he cites, has been known to scholars for ages. Back in 1996, Kenneth Hamilton published a lengthy article about the opera in Cambridge Opera Journal Vol.8,1. It includes an overview about the content and some musical examples from the sketchbook. It has been clear since then that some of the music could be reconstructed, albeit only vaguely.

By the way, the mysterious ‘German archive’ where this manuscript ‘was found’ is the Goethe- und Schiller Archiv in Weimar, where the world’s largest collection of Liszt manuscripts is housed today. Everything is properly catalogued and searchable.

For many people in trhe anglo-saxon world, ‘Weimar’ is in itself a mysterious place.

And it’s mystery is only exceeded by it’s power!

This is why I hate auto-correct. More so, if the language corrected isn’t the same as the OS’s language.

Dr Trippett is of course the scholar who persuaded the University of Cambridge to create a post uniquely for him, so that they could benefit from his over large research grant. He may be a fine scholar, but his modesty and intellectual honesty remain well concealed.

The casual slander in the comment above is pretty staggering. Trippett clearly acknowledges Kenneth Hamilton’s work in the Times interview, and explains in the YouTube video that the manuscript is in the Weimar archive and was catalogued there in the early twentieth century. Why the bilious reaction here ‘Charles Hedges’? Smacks of personal enmity. The press release might have been more detailed, but this is a remarkable bit of work that benefits anyone who loves Liszt’s music. When do we hear the whole thing?