Alastair Macaulay reviews a singer who conducts

OrchestrasThe Alastair Macualay Review:

A number of singers – Placido Domingo and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau the most renowned – have also been conductors. It’s probably not a first to have someone sing and conduct at the same time, as happened at Thursday’s London Symphony Orchestra concert, but it’s certainly a mighty rare event. Thursday’s singer-conductor was the Canadian soprano-conductor Barbara Hannigan; this March 13 LSO concert of hers was the first of three at the Barbican Hall.

The first half of the concert were rarities by Roussel (symphonic fragments from “Le Festin de l’Araignée” – “The Spider’s Banquet”) and Ravel (“Histoires naturelles”), with Hannigan conducting. After the interval, she returned with Benjamin Britten’s superlative orchestral song-cycle “Les Illuminations.” She turned round to the audience to deliver the vocal parts, then turned back again to direct the orchestra whenever she wasn’t singing. (Sometimes, while she faced front, she used gestures to cue the players.) This was quite a feat – a feat of stamina, too, since she then returned a minute later to conduct the full orchestra in Haydn’s glorious “London” symphony (no 104).

The string players, perfectly co-ordinated whichever way Hannigan was facing, rose to the thrilling challenge of “Les Illuminations.” Britten here is setting poems from Arthur Rimbaud’s radical eponymous suite of visionary writing; some of his most imaginatively poetic music is for the strings, now frenzied, now dancing, now shimmering, heightening the sheer audacity of Rimbaud’s creations. The score, written for “high voice”, should logically work best with a tenor, voicing Rimbaud’s brilliant, angry-young-man utterances, but Britten gave the world premiere to a soprano; I always find it blooms best with the soprano voice. Hannigan is not in the league of Suzanne Danco and Heather Harper, the song-cycle’s best interpreters on record – she has no chest tones, her French diction is occasionally blurry, and her manner is sometimes knowing – but she has marvellous attack and drive, floats some of the vocal lines like gossamer, and brings intelligence and personal involvement to every part of the cycle. Likewise I’m known Britten’s score conducted with even more bite, speed, and frenzy, but Hannigan certainly caught its flair, its sensuality, and its imagination.

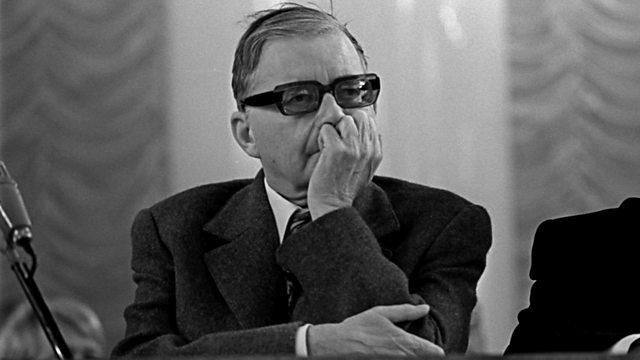

Political correctness should prevent one from adding that Hannigan is also very easy on the eye, but there you are – she’s a beauty. Her long blonde hair is part of the spectacle when she’s addressing the orchestra, while her bright eyes and jawline are no less part when she’s facing front. When conducting the other three works, she wore glasses (always removing them to face the audience).

I was happy to watch the sheer variety of her arm movements. Often, her long fingers, subtly parted, were like a ballerina’s, but that resemblance did not prepare us for the punching force of several of her gestures. Mainly, she’s economical in movement: her way with the players is one of dialogue, not just of charioteer control.

The suite from Roussel’s “Spider’s Banquet” (1913) was a highly picturesque close-up of insect life (and death) in one corner of a garden, with a wealth of different colours to depict ants, a butterfly, the spider, and a mayfly. This is late Romanticism, slow and engrossing – but very far from the wry, droll modernism of Ravel’s study of five enimals in “Histoires naturelles” (1907), here given by the French baritone Stéphane Degout in an orchestral version arranged by Anthony Girard. Ravel set five texts from Jules Renard’s strange, funny, prose poems – the peacock, the cricket, the swan, the kingfisher, the guinea-fowl – with a wonderfully lucid heightening of their words.

Degout, an elegant singer with ideal diction, has recently played Michael in the premiere performances of Mark-Anthony Turnage’s opera “Festen”. Singing the Ravel song cycle in his own language, he catches both the songs’ detachment and their identification with these animals.

Haydn’s “London” symphony, shaped by Hannigan with great verve and élan, proved an ideal conclusion to this fare. Haydn is my “home” composer: I’m never uncomfortable with his music and always stimulated by it. I love in particular the sense of masterly experimentation that his music invariably has: you can feel him trying out the effect of a pause, a harmony, a melody, a rhythm – all with infinite mastery and eloquence – taking us gently where we never quite imagined, while always celebrating the marvels of civilisation and nature. Hannigan led this last of Haydn’s symphonies (I adore all 104 of them) through its many moods of ceremony, dramatic tension, urbane power, pastoral charm (the pastoral of a London park), spiritual repose, so that the ear and mind were constantly piqued, guided, surprised.

The art of concert planning is a subtle one. On paper, Hannigan’s three March 2025 LSO concerts – the others will be on March 19-20 (interleaved with quite different fare conducted by Antonio Pappano on March 15 and 23)- are admirably refreshing. Each features a Haydn symphony (no 39 on March 19 and 20). This evening’s Roussel will be replaced on March 19-20 by the Bartók “Miraculous Mandarin” suite (another ballet seldom seen onstage). And on March 20 Hannigan on March 19-20 will sing the recent composition, “Je ne suis pas une fable à conter” by Golfam Khayam and (on March 20) Sibelius’s “Luonnotar”. (Her March 20 concert also includes Debussy’s “Syrinx” and Claude Vivier’s “Orion”.) “Je ne suis pas une fable à conter” (“I’m not a tale to be told”) is a celebration of Persian culture to poems by Ahmad Shamlou, to be sung in both French and Farsi, involving elements of orchestral improvisation at each performance. This is fascinatingly eclectic scheduling, promising to take us all in many different directions.

image: Mark Allan/LSO

Comments