A Boston player remembers life with Seiji

OrchestrasBSO bass trombonist Douglas Yeo has shared with us some intimate memories of the late music director:

I arrived at my office at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign at 7:00 am to get ready for a full day of teaching. As is my habit before taking out my trombone and warming up, I opened my laptop, quickly checked my email, and scanned the morning’s news headlines where I read an announcement that conductor Seiji Ozawa had died on Tuesday, February 6, at the age of 88.

I burst into tears and cried like a baby.

Seiji Ozawa hired me into the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1985. At age 29, I joined the BSO for a career that extended until 2012, 27 years of memorable music making and other wonderful experiences. Seiji was music director of the BSO from 1973 to 2002, and his death brings back unforgettable memories of the intersection of our lives. Here is the Seiji Ozawa I knew and will always remember…

The audition was held in Spring 1984 and at the end of the day, I was the last candidate standing. But I was not offered the position. Seiji told me he liked my playing very much but he would like me to make some small changes to my sound and approach. There would be another audition later in the year but in the meantime, he asked me to come to Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, to play two weeks of concerts, then go to Europe with the BSO for three weeks, and then return to Boston to make a recording of Richard Strauss’ Don Quixote with Yo-Yo Ma as soloist. I was thrilled to accept the offer of weeks to play with the BSO. Those weeks at Tanglewood, in Europe, and in Boston were unforgettable. Symphony No. 2 of Gustav Mahler with Jessye Norman as soloist, Don Quixote and the Dvorak Cello Concerto with Yo-Yo. Dvorak Symphony No. 9 and Shostakovich Symphony No. 10, and more.

I returned home to Baltimore and at a second audition in December 1984, I won the bass trombone position with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and began my tenure there in May 1985.

Thus began my remarkable adventure as a member of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. It was electrifying to sit under Seiji’s baton. Yes, we all called him Seiji. Not maestro, not Mr. Ozawa. Seiji saw the BSO as a family. He cared deeply about the orchestra, the institution, its history, and its members. Seiji was so much more than a superb musician. He cared. He cared so much about so many things. And he loved Boston. Unlike so many music directors today, Seiji was deeply involved in the city of Boston, and Tanglewood was his happy place.

Seiji Ozawa was a truly great artist, musician, conductor. We all knew it; the world knew it. But for me, his musical persona was secondary to the fact that he was a genuine, caring human being. He loved the Boston Symphony Orchestra and its players. He showed this over and over. I had many personal encounters with Seiji, memorable moments that are frozen in time, so indelibly imprinted in my mind. One of the most significant is from the summer of 1989 when my oldest daughter, Linda, and I were in a horrific car accident at Tanglewood (a fuel oil truck sped through a red light and hit us broadside; we never saw it coming). Linda and I were taken by ambulance to the hospital; she was seriously injured and was in a coma. At first it was touch and go whether or not Linda would live but we prayed and prayed and prayed. The day after the accident, Seiji came to the hospital to visit our family. He had no entourage; he came without an announcement. He didn’t come as my boss, as “Music Director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.” There were no cameras or microphones around. He came as the father of two children of his own who was visiting a friend whose daughter was profoundly injured. Seiji and I hugged and cried. We walked into the intensive care unit together to see Linda; Seiji was shaken. Fortunately, God gave us a miracle and Linda recovered—today she is a fine bass trombonist and music teacher, and the mother of our grandchildren—to see her now is a testament to God’s mercy, grace, and healing power. And Seiji’s visit—a visit that came with no fanfare—remains in my mind as I remember him as not only a great musician, but as a caring person….

I also remember many conversations I had with Seiji about God and faith. When we met and spoke in private, he opened up about many things. Seiji’s mother was a Christian; his father was Buddhist. In a conversation, he told me that the first Western music he ever heard was his mother singing to him, in English, the old African-American spiritual, “Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen, nobody knows but Jesus.” When asked in an interview what he thought was the most important piece of classical music ever written, Seiji said—without hesitation—”The Bach Saint Matthew Passion.”

More here.

This is deeply moving. Thank you for sharing.

The link at the bottom wasn’t working when I read the blogpost.

A very lovely and touching tribute to the wonderful Seiji Ozawa

Wonderful tribute to a wonderful man.

This moving tribute by a bona-fide BSO player should put to rest rumors of Ozawa’s “lack of capabilities” or “not well liked by players”.

Ask Charlie Schlueter, lol….And quite a few players from back then…..More then half of the players wanted him replaced from the mid 80s on…They wanted Sir Colin Davis and Bernard Haitink as music directors. With some reason!

Wonderful article. Thank you.

What troll jacka***s would thumbs down my comment? You are despicable and lacking in basic human dignity.

“Yes, we all called him Seiji. Not maestro, not Mr. Ozawa. Seiji saw the BSO as a family. ”

Interesting perspective from the BSO.

From *his* point of view, Ozawa said this about his experience at the New York Philharmonic with Bernstein:

“…Everybody called him “Lenny.” They call me by my first name, too, but it was way more extreme with him. Some musicians would assume, as a result, that they could get away with anything, and they’d yell stuff like, “Hey, Lenny, that must be wrong.” Keep that up, and your rehearsals won’t go anywhere. They won’t end on time, for one thing. … The music can lose its coherence. That would happen now and then. Back when Saito Kinen was just getting started, we had people calling me “Seiji” and people calling me “Mr. Ozawa,” and people calling me “Maestro.” It was pretty confusing. That’s when it struck me—it must have been like this for Lenny.”

Excerpt From: Haruki Murakami. “Absolutely on Music: Conversations.” Apple Books.

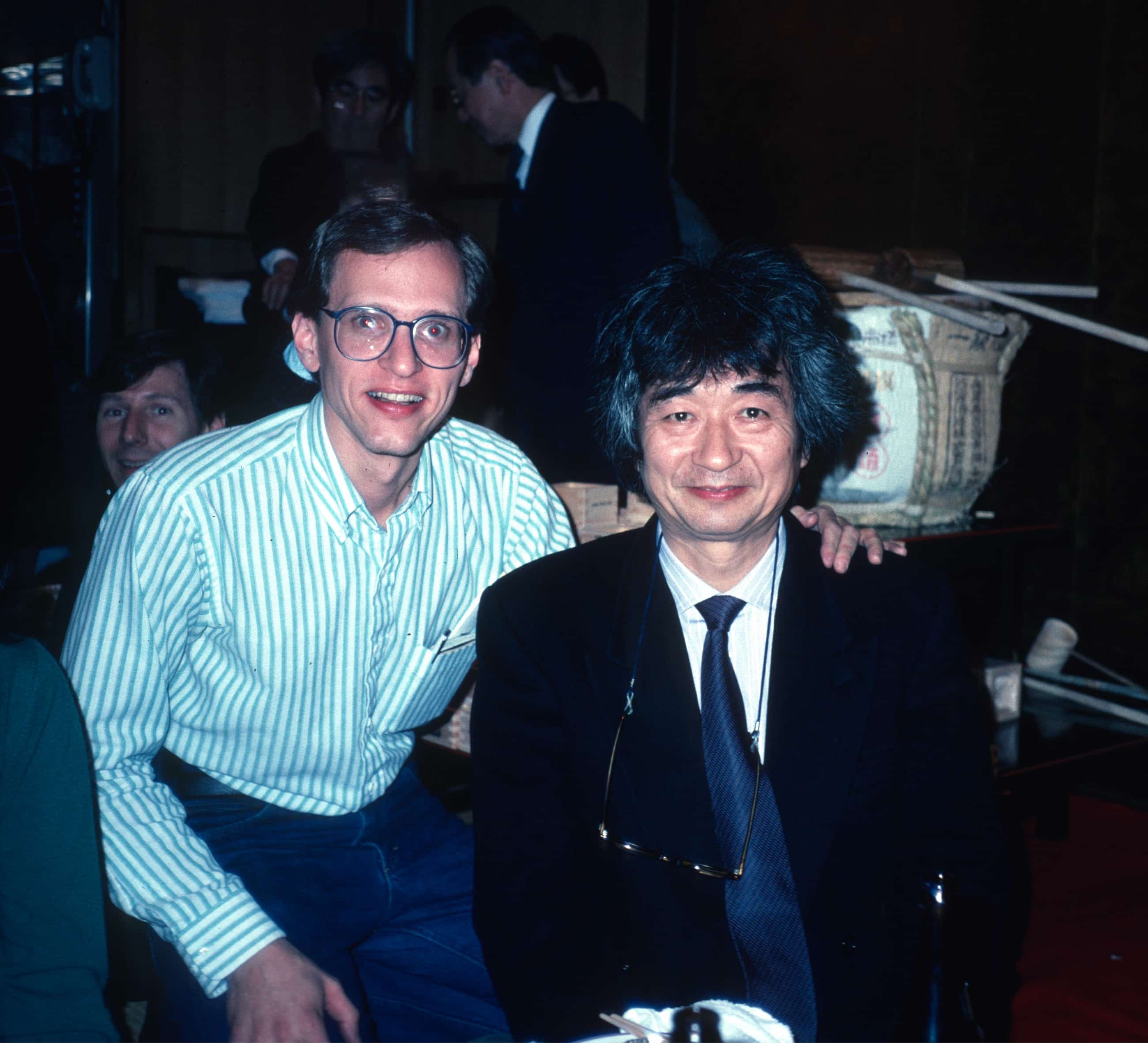

By the way, that is a most unusual photo with the conductor standing behind the bass trombone on stage… I’ve never ever seen that, the conductor standing behind a player during rehearsal like a teacher making sure the student is playing the part correctly, LOL. What’s going on there? Who’s that guy standing next to him? Why was a photographer on hand to snap that picture? What were you playing? A thousand and one questions!

William Steinberg did it all the time wandering around behind the players

The guy standing next to Seiji behind the trombones is Boston Pops conductor Keith Lockhart.

That looks like a very young Keith Lockhart standing next to the Maestro. It is an unusual picture.

Click through to the full post, where he gives details and context for the picture. (That’s Keith Lockhart, on the day his Boston Pops appointment was announced!)

Thanks, very helpful, though it still doesn’t explain 1) why they parked themselves behind the trombones, 2) why Ozawa is earnestly reading the trombone part with a benevolent smile, 3) why at the same time Lockhart is staring absently into space with an expression like he’s sucking on a slice of lemon, and the biggest mystery of all, if both conductors are standing behind them, then 4) who the heck is conducting, whom the trombones are looking at, and 5) why are they still playing?

Yeo asks for a caption, well here goes: “BSO trombones claim mind-reading skills with no need to to watch conductor; BSO conductors test that claim be standing behind them and mentally conducting.”

Very interesting to read opinion of people who have approached these musical “monsters”…. thanks for sharing.

Thanks for the link, Norman. A wonderful musician. An even better human being. The BSO was fortunate and blessed to have had the opportunity to be led by one so deserving of such a rich and lasing legacy.

Lovely tribute by Doug Yeo. Great that you shared it with us. Most of us who knew Seiji well loved him. He was very special, deeply emotional, caring and full of positive energy.