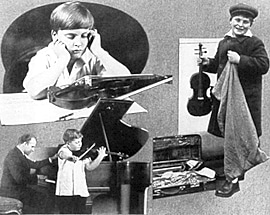

Stars in short pants (6): Menuhin, 13

mainHerbert Giesen is the pianist.

A couple of weeks after his 77th birthday,…

The Washington Examiner reports that next Tuesday’s celebration…

The death has been made known of Günther…

The CBSO music director Kazuki Yamada, who last…

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Comments