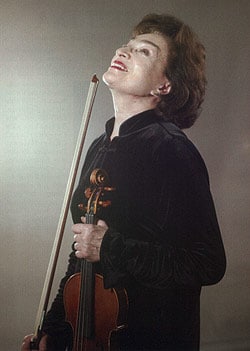

Death of an outstanding Oistrakh disciple

mainThe wonderful Russian violinist Nina Beilina has died in New York at the age of 81.

A student of David Oistrakh at the Moscow Conservatoire, she won gold medal at the 1961 Enescu contest and came third in the 1962 Tchaikovsky Competition (winner: Boris Gutnikov), going on to a considerable career in Russia and abroad.

In 1977, after her husband’s death, she settled with her son Emil Chudnovsky in New York, becoming a professor at Mannes School of Music. Emil is now a successful concert violinist.

There will be a memorial service at 12 noon on Sunday, December 2, 2018 at Riverside Memorial Chapel (180 W 76th St., New York, NY).

I was his post-graduate student, but had an unusual relationship with him. To understand why it was unusual, I have to take you behind the scenes to the personal politics of the Moscow Conservatory. In the Conservatory, there were two factions among the violin faculty, roughly speaking: there was the clique to which my first teacher, Abraham Yampolsky, belonged and then there was the Oistrakh faction. As a Yampolsky student, I was a Montague to the Oistrakh Capulets.

When I graduated, as a straight-A student, from the Conservatory with the equivalent of a B.A. in hand, I applied to the Conservatory’s post-graduate department. I can only speculate as to why I was not even allowed to audition; that is to say, my application documents were summarily rejected. Was it the line identifying my nationality in my internal passport? The line which read “Nationality: Jewish”? Or was it the “membership” in the wrong clique? Either way, what it certainly wasn’t, was my grades (all A’s, remember) or my playing – since I wasn’t even allowed to audition.

So, understandably angry, I left Moscow to go to Leningrad to study with Julius Eidlin. He was a disciple of Leopold Auer, and I am immensely grateful for the time I had to work with him. As a parenthetical aside, I can say that he re-did my Bach completely from the over-Romantic approach then popular in the Soviet Union to something approaching a Szeryng mentality. But I digress.

What is relevant is that Eidlin became very, very ill. He was unable to continue teaching and yet I had no “home” to which to return in Moscow since Yampolsky had passed away. So Eidlin made the olive branch move: he called David Oistrakh, asking him to accept me. Thus – a phone call as a flag of truce. And so Oistrakh took me on as his student back in Moscow, at the Conservatory, towards the end of my Masters equivalent….

As a violinist, he was what I call a “jeweler”. This meant that he put every piece under a virtual microscope regarding every shift, every bowing. Everything had to be completely secure, consistent and unshakable. I remember one lesson which he tape-recorded, then played the tape back to me at a slower speed. Obviously, everything was at a much lower pitch, but one could hear all the micro-events – a shaky shift here, a clumsy bowing there, an unfocused attack elsewhere – and it was incredibly instructive….

More here.

She also founded a chamber orchestra called Bachanalia, which was composed of other émigré Russians, which gave a wonderful series of concerts every year.

I remember hearing her give a terrific rendition of the Tchaikovsky concerto with the Chicago Symphony (on the radio) not long after her arrival in the U.S.. And several years later saw her in Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnole in Seattle.