Book Club: Inside the lines of Busch and Serkin

mainFrom our book club moderator, Anthea Kreston:

Welcome to the Fortnightly Music Book Club. This week, in addition to the second portion of our video interview of Roberto Dìaz, President and CEO of Curtis Institute of Music, we are privy to inside glimpses into the fascinating world of the Serkin/Busch family. Reader questions are being answered by David Ludwig, composer and faculty at Curtis, and grandson to Rudi Serkin and Irene Busch.

The three books, all related to Curtis and its Directors, are:

Powerhouse

A Life (Rudolf Serkin)

I Really Should be Practicing (Gary Graffman)

Anthea Kreston:

In these three books, the reader gets a clear sense that the Directorship of Curtis has both managed to remain true to its original ideas from 1924, founded on the great European and Russian traditions, while at the same time moving forward and leading the way to the future boldly. I even sense this in the three generations of Serkin family which has been an integral, and unbroken part of Curtis. Can you tell us about your specific relation to Rudi and Peter Serkin, The Busches, and how do you feel that you are similar or different from these generations (and them from one another).

David Ludwig:

Rudolf Serkin is my grandfather, which for some reason is confusing for people (mostly because I have my father’s last name, I think…) He was my mother’s (Elizabeth Serkin) father (and so Peter is my uncle—her younger brother). He died when I was a teenager-just starting college—and I spent time with him all my life until then—went to concerts when he played in Philly or New York, and would usually visit for holidays in Vermont. He was the most amazing grandparent you could imagine and I think about him all the time. I got up the courage to talk to him about music as I was really beginning to be comfortable in my desire to be a composer, and he shared with me all sorts of things about his time studying with Schoenberg et al when he was young, and many of his colleagues (I was a guitar player, and he told me lots of stories about his friendship with Segovia, for instance…)

My grandmother was Irene Busch-Serkin. Her father was Adolf Busch, the violinist, and so Busch is my great grandfather.

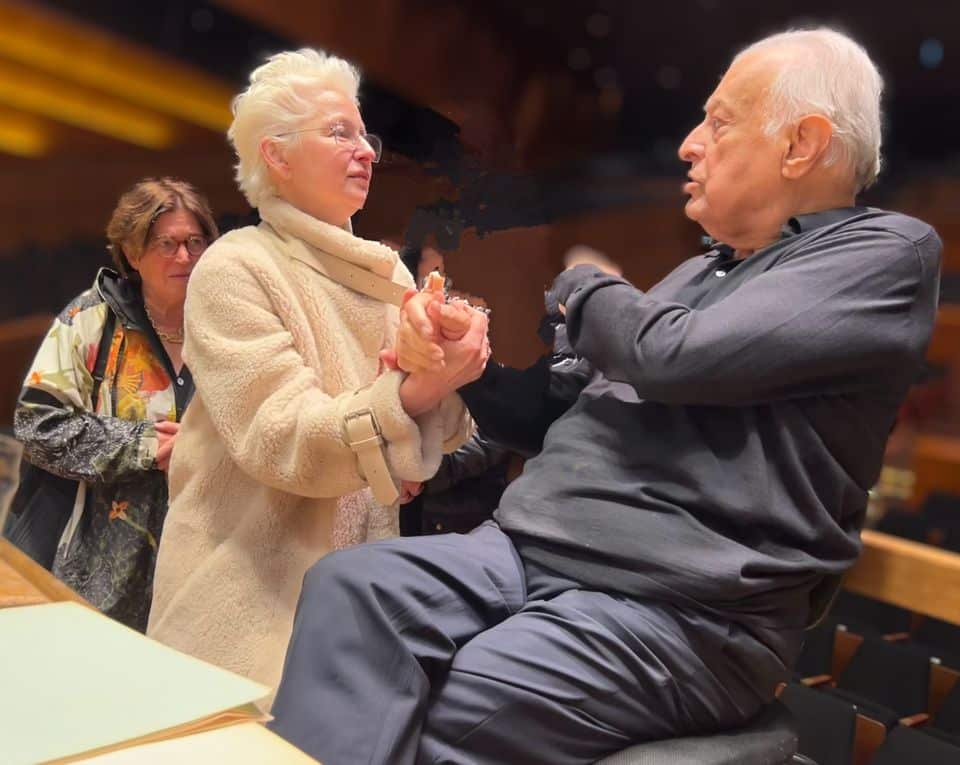

Peter has been an amazing presence in my life, and actually Curtis brought us closer together this year when the school did its European tour. That was the most time I’d spent consistently with him. To see his reverence for the music he performed with the orchestra (Brahms 1) and the reverence, in turn, shared by the students was very inspiring. It was reminder of why we make music––at Peter’s last performance on the tour the students lined up in scores to take a picture with him. I think he’s a consummate artist (as biased as I might be!) and adore his programming choices, which shows the widest perspective of our musical tradition that I know.

When I was coming up I never volunteered my family background because I wanted to do my own thing without the onus of that history or the assumption of validity that comes with it. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to embrace this history and be openly proud of where I come from. I don’t see these family members from my past as casting shadows, but as lights along the way.

At Curtis, I feel my grandfather’s presence strongly in the school’s emphasis on chamber music, practice, and technique as a vehicle to artistry. I know he broadened the school’s purview, and felt the importance of opera and other programs, as well—in many ways he prepared Curtis artistically to continue artistically long after he left. How the school has evolved in the past decade I feel is really positive, too; there are a wide array of options for students to pursue in their studies, a vitality and importance in contemporary music, and the means to explore the world as a young artist—all keeping a focus on the fact that being a great musician first is the key that unlocks the door to everything else.

The short and longer answer to your question is that I feel my grandfather’s presence alive and well at Curtis—not just in myself, but in all of the people still there who knew him as a mentor or who had mentors who worked with him. This is a kind of inheritance passed down, of which I am very aware, and I am very grateful to be a part of it both in my life as an artist and teacher—and as a six year old kid who used to run around outside causing mayhem with his grandfather in Vermont!

Comments