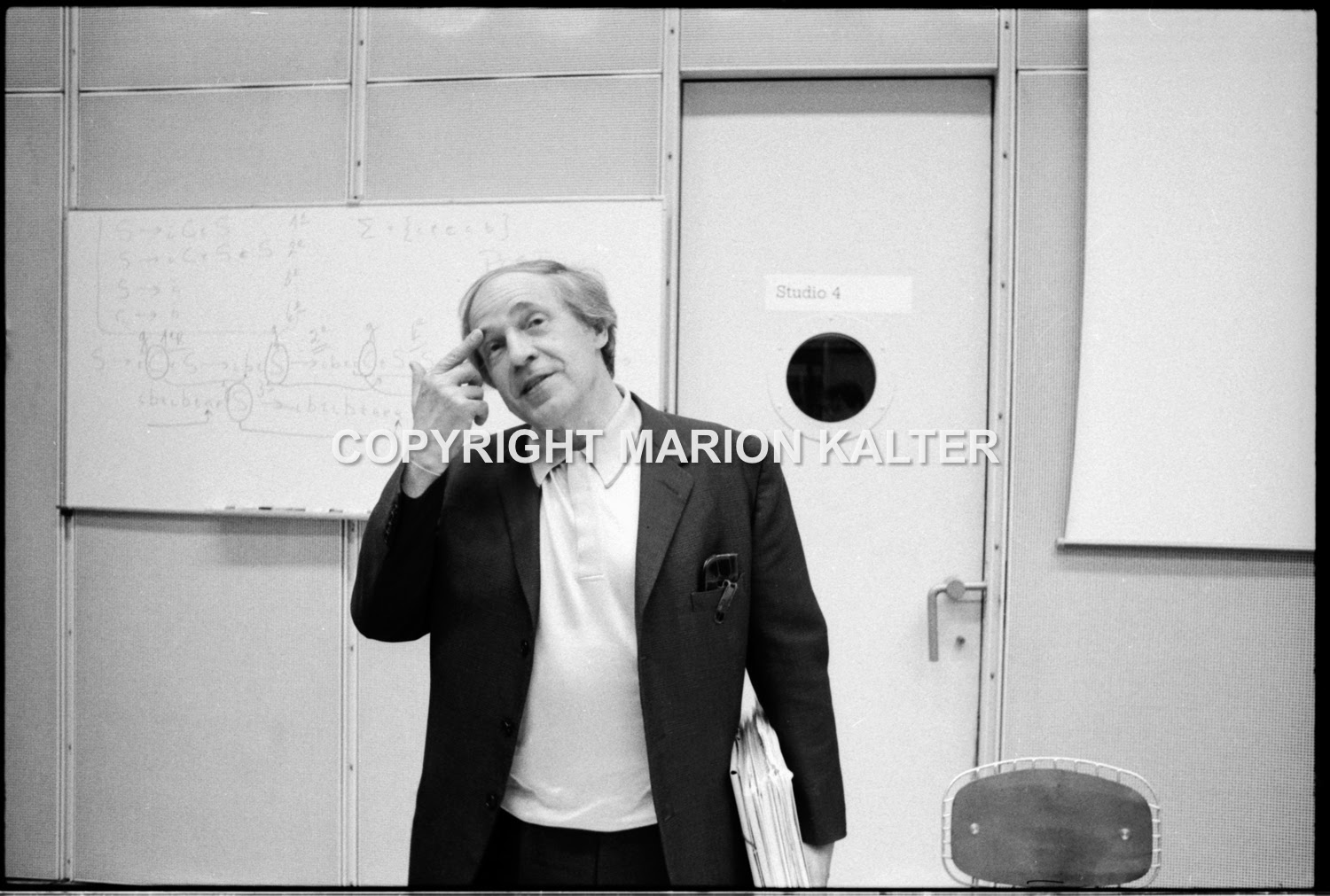

Untold history: Pierre Boulez and the nuclear deterrent

mainBoulez was a man of many parts. From my current essay in Standpoint magazine:

Pierre Boulez is showing me around his subterranean Ircam labyrinth beside the Pompidou Centre when we come to a locked door marked “private”. “What’s in there?” I ask.

“I can’t tell you,” says the boss, his voice dropping to a whisper.

Ircam, the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique, was the ransom a president paid to bring Boulez home from self-imposed exile. “President Pompidou asked me outright: would you come back to France? I said: if I return it will not be to conduct an orchestra when I have better opportunities abroad. For the idea of Ircam, though, I would leave everything.”

On the phone to the Elysée, he described an idyll where scientists and composers would work with computers to invent music of the future. Without further detail, Pompidou signed on to the vision, and the cheque.

Was there more here than met my ear? That day, deep beneath the Paris pavements, Boulez whispered that behind the locked door his technical team was developing acoustic warfare devices for the French navy. I asked him to repeat that secret, to make sure I had understood him correctly. He did. I wasn’t sure whether to gulp or to giggle.

Beside me was a leader of the musical avant-garde, a man so dangerous that mothers threatened infants with a blast of Boulez if they didn’t eat their soup, a composer of idées fixes and doctrinaire ideology who, by some twist of French logic, was apparently applying his brain to making weapons for a navy whose only current war was against Greenpeace nuclear saboteurs.

Read on here.

Comments