The night I smashed the stage in Mahler 6

mainGraham Johns got to try out his new Hammerschlag in Mahler’s sixth symphony at Liverpool last night and it pratically stopped shipping on the Mersey. What a whack! Two, actually. And the Scherzo performed before the Andante, which is my presently preferred order. A terrific interpretation of the terror-inducing Sixth by Vasily Petrenko and the Phil.

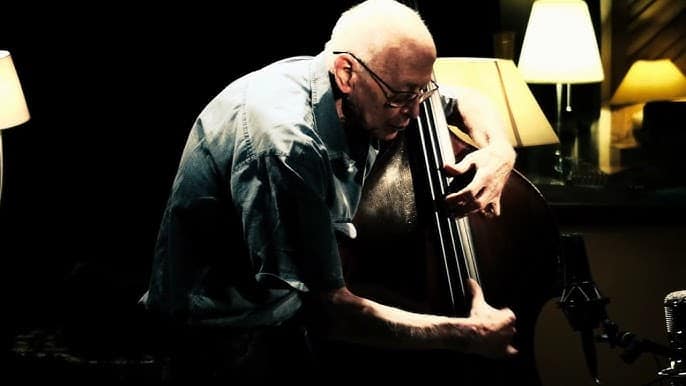

But back to the whacks. You will recall that Graham made his own noisebox for the performance. He did so, he tells me, in conjunction with Roger Cline, double-bass of the Chicago Symphony, who made the moveable diaphragm that gave the box its traffic stopping resonance. Roger is a very talented carpenter who has made all sorts of percussion instruments over the years, including bamboo whips and a volume controllable ratchet.

Where was I? Oh, the stage.

So before the performance Graham mentioned to me that the last symphony they played at the Phil before its major refurbishment20-odd years ago was Mahler 6. What if? he thought. So he got permission from the Phil admin and warned the conductor in advance.

In the finale of M6 he lifted his hammer and – smash! – went right through the stage floor. Smash again! Second blow. After that, the demolition crew didn’t have much left to do.

My old teacher at Hochschule Vienna told me he remembered performances where the percussionist would just whack the wooden platform on which the orchestra in the “Goldener Saal” (GMVS) with a huge wooden hammer causing dust to rise from underneath. He regretted the “modern trend” of using contraptions. He also mentioned his disgust at a touring London orchestra using some woodden box that was not actually hammered on, but triggered by some kind of mechanism. Anybody know about that?

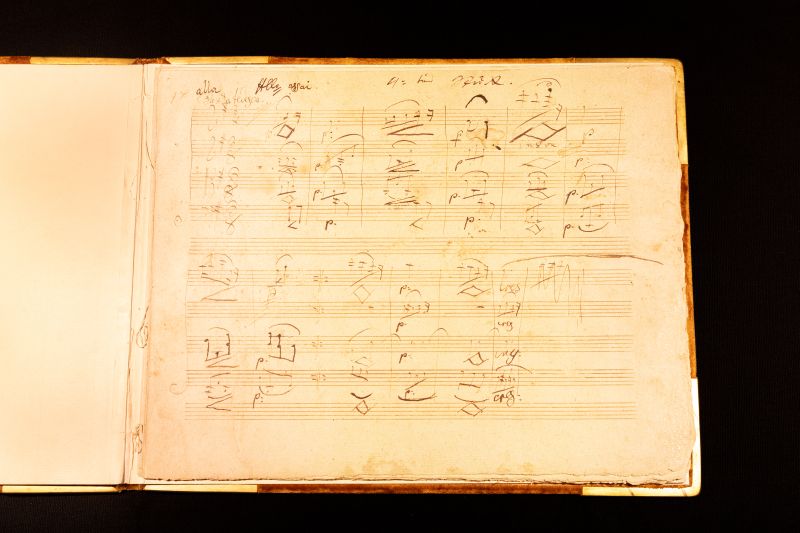

I’m fascinated by this comment since such a “rendition” of the hammer blow is probably more of what Mahler had in mind. And, coming from Vienna, this might be a reflection of an authentic Mahlerian performance practice. The use of “contraptions” is indeed unfortunate as they tend to overhype these moments. They might be the blows of fate or, indeed, fatal blows, but I don’t think they are meant to sound apocalyptic. It’s possible that Mahler had originally envisioned as many as 5 hammer blows in this movement, the first as early as the 9th measure. A tectonic hammer box noise that early in the movement would distract mightily from the musical events surrounding it. Even the three surviving blows (I’m for the restoration of the third) tend to do this.

Still, the attention devoted to these hammer blows, and to the order of the two middle movements are both small potatoes compared to the big problem of the orchestral strings not being seated in what, for Mahler and all other orchestral works of this period, is the only historically correct layout: divided violins, cellos on the left (basses behind the cellos or along the rear of the orchestra) and violas to the right inside the second violins. Mahler depends on this layout for countless “effects” in virtually every moment the strings are playing, not just three brief moments in the Finale of the Sixth.

Enjoyed Petrenko’s chilling version last night very much. Less is more. Not so self indulgent as many a modern day conductor. Scherzo second – good, but only two hammer blows and I don’t think he separated the violins. Yet again the cellos have some terric rasping moments, so seeing them take front stage right is also very dramatic. Btw, NL was his usual perky self.

More here:

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/classical/news/why-a-huge-mallet-takes-centre-stage-in-gustav-mahlers-symphony-no-6-a6725856.html

We know from recent research that Mahler, while writing nr 6, had to work-off his frustration about his wife. In Freud’s papers some notes were found referring to Mahler’s 1st visit to Freud in a hotel in Bad Ischl, secretly (his 2nd visit took place in Leiden, Netherlands, much later). He had told Alma that he took the waters for his haemorids but in reality to get the anger off his chest about his wife continuous complaining about his prohibition of her composing, just when she was “so full of ideas all the time”. He suffered greatly and regularly at breakfast when she would sing her themes while he tried to concentrate on the list of singers at the opera to be dismissed that day. After the session in Bad Ischl, while Mahler was struggling himself into his coat, he heard Dr Freud smashing something heavvy. Mahler returned into the room and asked what was the matter. Freud, visibly relieved, informed him that he had just ventilated some frustration which had been built-up during the session, whereupon Maher said: “Well – maybe I should do that TOO!” They sat together again and designed, on one of the empty pages of Freud’s diary, a big wooden box which would be filled with Alma’s manuscripts, on which the husband would then administer a big blow with a big hammer. After having tried that out various times at home back in Vienna, Mahler wrote it into his symphony, but gave-in to the pressure of his wife to restrict the blows to two instead of the original four which were advised by Dr Freud. “These two blows were more than enough, the one on my own compositions and the other on my cooking”, she had said.

“It is quite extraordinary how much we can unearth nowadays with the help of combined research results from different disciplines of the humanities”, Dr. Kegelstumpf from the University of Vienna told at the press conference in 2011. “The discovery of Freud’s notes goes beautifully together with the now available musicological explanation of the notes of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, thanks to united efforts of both psychological historiography and advanced musicology. We hope to find similar results with Bruckner’s symphonies and 19C railway engineering in the near future.” (From the Musikalische Beobachter Wien, 14 June 2011)

When Marin Alsop was doing the 6th at the Colorado Symphony in the early 200s, the stage wall was being used (sounded good, too), but on the last whang, the hammer went right through it!