Quartet joy: Anthea’s stolen violin is returned

mainIn place of her weekly diary, Anthea Kreston of the Artemis Quartet has asked us to publish her translation of a Süddeutsche Zeitung magazine feature on the theft of her violin early this year. The article is republished with permission.

You can read the German original here. It is an excellent, sensitive piece of journalism.

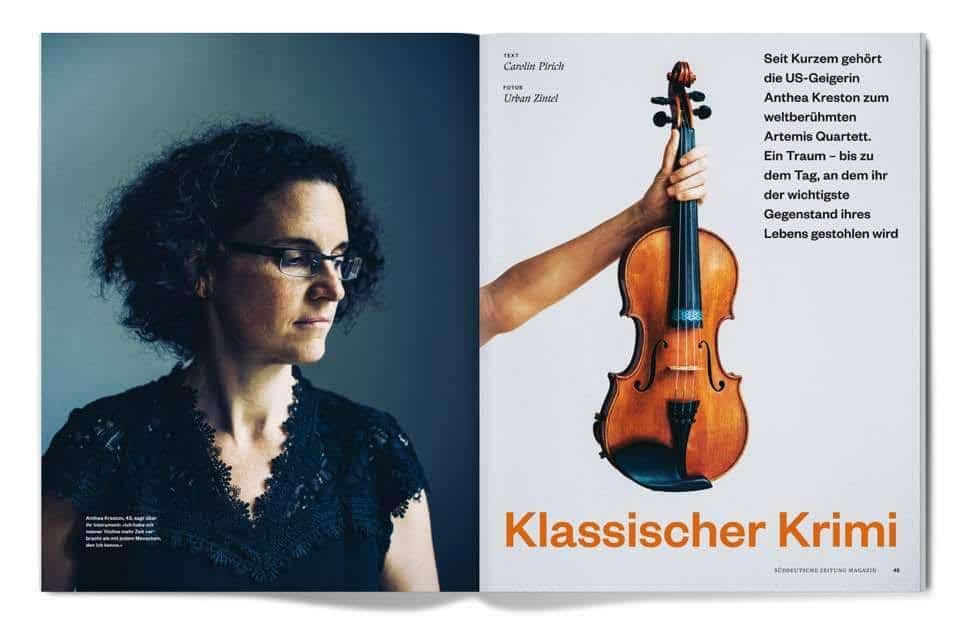

Classic Crime

Written by Carolin Pirich

Photos by Urban Zintel

(Loose translation by Anthea, with permission by the newspaper)

When the ICE 279 train stops at the Mannheim station mid-January 2016, American Anthea Kreston leaves her seat for about 40 seconds – a terrible mistake.

She pushes her violin case into the luggage rack above the seats and looks around: the car is quite full. Usually she sits with her colleagues on trips, but this time they didn’t reserve seats. They arrived early in the morning at the Berlin main train station and spread out to four different compartments. Around Anthea Kreston one fellow traveler sleeps, another types on his IPad. She has already exchanged a few words in German with the older gentleman – who was going where and why. So you do know some words in German, Anthea. He is wearing a sweater and trousers. Kreston estimates him to be in his 60’s.

A few hundred miles further, Kreston recaptured his gaze, sitting at the opposite window. She quietly understands that they have a bargain: he will pay attention to her violin case while she was away. In doing so, she does not expect to need a watchdog. The violin case is worn out, inconspicuous, and he is so close to her that she cannot imagine that he could suddenly disappear.

The violin in the case is one of the few objects that Kreston has taken from her old life into her new life, from the life of a violinist from the vastness of America into the intimate, complicated relationship of the most famous German string quartet, the Artemis Quartet. After the violist Friedemann Weigel took his life in 2015, the quartet was looking for a way to close the gap. The second violinist Gregor Sigl took the viola position, and now a successor to Sigl was sought. The person should speak German well and live in Berlin. This is what they sought.

After half a year searching, and 156 candidates, the job went to a very tall, very slender, brown-haired American woman who lived with two small daughters and her husband in Corvallis, Oregon, in the Pacific NW of the USA, whose only words on German were “Good Afternoon”. When Kreston recounts this story today, it is as if a fairy would have waved her wand and replanted a family from a tiny town in Oregon, in the midst of the American mainland and the hazelnut capitol, with a harp glissando and a glittering star, into an old apartment on a busy street in Berlin-Charlottenberg.

Half a year ago they moved, and Kreston still pauses with great amazement when she tells, in her broad American, how she came to Berlin to audition in the end of January. She, her husband and two daughters had three weeks to sell the house and two cars, and unpack their suitcases in Berlin. She had always dreamed of being a part of such an important quartet, in which one kneeled before the thousand shades of a feeling as they explored the music. But she had ruled out this possibility. She, and American woman, who chats about her life, laughs, laughs more, and is unable to get rid of her quirky accent, as a part of a collective who lives in seriousness, in front of the public – she could hardly be European. It is a wonder! A chance of a life-time! And now she makes the new, the American, the banal but serious mistake of leaving her seat on the ICE without her violin.

When Kreston returns to her place, she throws an experienced look at the luggage rack – short contact with her violin, the wooden extension of her body, but there is nothing there. She looks again: nothing. She pushes the suitcases aside, Kreston is very tall, it is easy for her to rummage in the luggage rack – still nothing. Her heart pounds from the inside against her ribs, her breath goes faster. She looks behind the seat, looks around at the faces, and her gaze sticks to the older gentleman in the sweater. She speaks to him: Please, she tries in German, my German is terrible, excuse me, have you seen my violin? A young man, yes, he passed and took the violin case with him.

She does not cry, What!? She does not say: but why did you not stop him?

Kreston breathed out. Perhaps one of the colleagues took the case. Eckart Runge, the cellist. The elderly gentleman may have seen him. A man with big blue eyes. Kreston would call Runge a young man.

The Artemis Quartet is on its way to a concert in Freiburg, the thirtieth concert that Kreston plays with them, thirty concerts in three months. They are finding each other, slowly.

After Friedemann Weigle had taken his life, it seemed as if the quartet was freezing. Such a string quartet is more than a musical formation. More than an orchestra, much more than a soloist, the string quartet mixes the professional with the private until there is no longer any difference. Everyone knows what it is like inside the others. Every day is emotional. They speak in rehearsal: is the sadness in this measure emptiness or disparity, longing, or helplessness? When did you last feel like this?

When Kreston sent a Facebook message in November a year ago with her application for the job to Runge, she did not write of glamorous names she had played with, did not mention any competitions, and did not list the names of famous concert halls she had played in. Such information, which can be read in any program about a musician, can impress, but it is bloodthirsty. Kreston wrote that she had two children and lived in Oregon, and she spoke about the quartet’s loss of Friedemann. Perhaps you remember, she wrote, twenty years ago, at a master’s course at the Juilliard School in New York, she was a tall girl with lots of curly hair. She was as real as she could be. She knows what it means to be in a string quartet. Being yourself is of utmost importance.

A string quartet is unconditionally interrelated. You plan together, you get together during holidays, schedules are decided years in advance. There is no second cast like an orchestra, which can find a substitute for an emergency. It’s like launching an expedition to Mars. When the space ship lifts, there is no going back.

In the ICE Kreston is looking at the finely cut face of the cellist. She trusts Runge – has he seen her violin alone and taken it to his compartment? Runge is soft and gentle and seems to be able to see all of life from above. Perhaps he took the case to check how cool she would be under pressure, the new member. Maybe it is a joke. A string quartet is said to be a “marriage of four”. With all the disadvantages of a marriage, but without the advantages, says Eckart Runge, whom they all call Ecki. Because they can call each other these funny short names.

It is 1:30 pm. Six and a half hours before the concert. Kreston can feel the sweat begin to start. Ecki does not have the violin. The violin is gone. One could also say in such a case: The hand is gone. For a musician, this sensation must be similar in the first moment of realization. Most musicians look for an instrument, and when they find it, they cling to it. They fall in love with the color palette, the joke, the way it interacts. Gregor Sigl, previously the second violinist, who today plays the viola of his deceased colleague, finds: playing on a very good instrument is like a conversation with a witty, funny person. “It is an effort”, he says, “but what comes back is even better than you anticipated”.

A violin is also a lucky charm, a faithful companion in the increasingly fast, hard and demanding world of musicians. The violinist Frank Peter Zimmerman described the relationship to his instrument as “Great Love”. When he had to return his “Lady Inchiquin ” to the donor in the spring of 2015, he spoke of a “very great tragedy”. Or the cellist Amadeo Baldovino : after his Stradivarius cello, the famous “Mara”, had disappeared in 1963 during a shipwreck in the Rio de la Planta and had disintegrated into many parts, he had to identify it. It seemed to him as if he were looking into the box as if it were a coffin.

“my violin speaks to me,” says Kreston. She closes the door to her apartment – old building, French doors, little furniture. They did not bring any furniture. She was born in Chicago, and the violin came from Chicago. She grew up with it. She has had this violin, and no other, since she was 14 years old. With this violin, she played her first concerts, won many competitions – against candidates whose instruments were worth 300,000 or 350,000 dollars, many times more expensive than hers. It is as if the violin knew every mistake, every moment of happiness, every piece Kreston played on her.

The sound of the violin is like the people of Chicago, she says: wide shoulders, sweeping gait, complex in a simple way. She exaggerates her American accent – it sounds nasal, broad, as if she had a hot potato in her mouth. As she speaks, she laughs and throws her head back. Her curls fly in all directions. She laughs a soft, warm laugh. She has what you would call the presence of an actress.

Her grandfather gave her the violin. In his will he left Anthea and her two older sisters ten thousand dollars each for an instrument. At 14, Kreston fell in love with the orange-colored wood of a violin. Carl Becker built it in 1928. “Becker wanted to build the violins as he thought Stradivari did, and so he chose this bright colored varnish,” she said. And that is why they call them “American Stradivaris”. In Germany, a violin maker said that a Becker is not a Ferrari, but a Volkswagen. Kreston’s violin is currently estimated as $75,000.

It is 24 minutes until the next stop in Karlsruhe, this is the time they have to find the violin. It could still be somewhere on the train. In these 24 minutes something unfolds in her colleagues that Kreston finds magical. The musicians are used to staying calm under pressure. In concert, they have to play at their highest level, while taking into account the weaknesses and strengths of the others. Now the colleagues translate this ability into a new goal: not to just play a concert. They begin to hunt. Considered, effective. Without reproaches.

Kreston looks frantically under the seats, in the luggage racks; only that night did she notice the bruises covering her arms and legs, a result of the search. Runge, cellist and son of a diplomat, talks to witnesses. Gregor Sigl, violist, checks all bathrooms, and researches the faces on the train: is someone nervous? Is someone trying to look unobtrusive? Vineta Sareika, first violinist, posts on Facebook that the Carl Becker was stolen from her new colleague.

Who could have stolen the violin? The case in which it lays is more sporty than noble, it could have also been a tennis racket. But – maybe someone followed her – did she notice anyone? Does the new violinist of the Artemis Quartet play a valuable instrument, and did someone wait for an inattentive moment during the tour? Again and again there are reports of musicians, tired after a concert, of constant travel, leaving their instruments (worth a single-family home) on the train, in a taxi, in an airplane.

Untold Karlsruhe: nothing. Kreston rises with Runge. They must go to the police in the station. Sareika’s Facebook entry reached, within a day, more than 100,000 people – thousands shared the post. Anyone handing in a violin to a violin dealer, built in 1928 by Carl Becker in Chicago, will now be a suspect.

In the mean time, violins which are like a Picasso, Chagall, a Pollock, become collectors items and an investment, and increase dramatically in price. While the Dow Jones index has grown twenty-fold since the 1960’s, top-of-the-line instruments have grown two-hundredfold. Every year, the price grows by twelve percent. The most expensive instrument is a viola by Antonio Stradivari, the “Macdonald”. It was offered for $45 million, saw the spotlight a few times, and disappeared again in the violin dealer’s safe, where it will remain until someone is willing to spend so much money on it.

For 16 million dollars a Guarneri del Gesù, the “Vieuxtemps” from 1741, changed owners and replaced the “Lady Blunt” Stradivari as the most expensive violin in the world. The “Vieuxtemps” is currently played by the American violinist Anne Akiko Meyers, as a permanent loan; The current owner of “Lady Blunt” has remained anonymous.

Again and again there are attempts to understand the secret of these instruments. Is it the wood? The vintage of certain pines? A fungus? The Venetian brackish water, in which the woods may have been situated during transport? Is it the vaulting of the top, the shape, the varnish? People scan the instruments with computers, they want to copy them. There are also attempts to deceive the myth. For example, the blind test; with virtuosos playing blindfolded on new violins and on Stradivaris, most of whom preferred the new violins. It does not change anything: the desire is unbroken.

On the way to the police station at Karlsruhe station, Kreston remembers adventurous stories of violent thefts, every musician knows them. For example, by Bronislaw Huberman. In 1936, at Carnegie Hall in New York, played Bach’s Concerto in E major on his second violin, a Guarneri. Someone crept into the dressing room and took his “Gibson” with him. It was only half a century later that the violin reappeared. A freelance musician confessed to his wife on the deathbed that he had stolen the “Gibson”. He had covered the violin with shoe polish to cover the glowing wood. Or the story of the then violinist of the Berliner Philharmoniker, Pierre Amoyal. His “Kochanski” was stolen in 1987. Only after four years and a high ransom did he get it back.

The 75,000 dollars worth Kreston’s violin are little compared to the astronomical prices of the others. Nevertheless, apart from the personal loss – few musicians, even fewer chamber musicians, can buy an expensive instrument themselves.

It’s 8pm. The audience in Freiburg is waiting for the performance of the Artemis Quartet. Behind the stage Kreston takes one violin after another in hand. Still on the train, her colleague, Vineta Sareika, had written to Freiburg professors, musicians, and students. She requested that a violin be made available so that the quartet does not have to cancel the concert. Now there are four violins in front of Kreston. She has one minute per instrument, then she has to decide. She plays a scale. It scratches horribly. Two, three chords. Kreston puts an instrument away and takes the next one. Each violin is different, each string has its own personality, which also differs on every centimeter between the scroll and bridge. Kreston played almost her whole life on her own instrument. To know a new violin, it takes months, she says, if not years.

“You have to forgive yourself in advance,” she says, “otherwise it will be terrible.” Forgive me for the stupid mistake of not taking the violin to the train. For the stress that caused her new colleague, just before a concert. She thinks of the ten or twelve places in the Shostakovich, which she will soon play, which will sound bad. Different than usual. Not only does she have to change. The entire quartet might be on the go during the concert. She must also forgive herself for that. Every thought that does not belong to music ruins the moment. The head must be free, the heart open.

“I will take this,” Kreston says to one of their colleagues. The violin sounds milky, warm, maternal. It is a baroque violin with strings of catgut, but Kreston does not know yet. They will soon play a middle Beethoven and a Shostakovich. Only in an emergency would a musician in a concert take a baroque violin with gut strings. She quickly puts on her concert dress, takes the bow, makes peace with the violin. Then the door opens, and Kreston follows Vineta Sareika.

It is this unconditionality which is so often referred to when talking about chamber music. It is the one that the Artemis Quartet has sought in the 156 candidates, vague somehow, intuitive. Now it becomes tangible, which means total surrender.

In the night after the concert in Freiburg, the first concert she played without her grandfather’s violin, Kreston does not sleep. She is making a poster, a photograph of the violin and her email address, which she has created specially for this. When a cat has run away or someone lost something, a small flyer in their little town in Oregon is stuck to each street corner, asking for help. Kreston offers a reward, 1250 euros. Not too low, it should be an incentive to deliver the violin. But not too high. The thief should not know that he is holding in his hands something worth more than the salary of a higher official, he should not realize the worth.

She takes the first train in the morning. Think of the bellies of American officers, the mug of black coffee with which they arm themselves. At the station in Mannheim Kreston buys donuts for the German station policemen. What she does not know: they must not eat them, so are the German laws.

She sits in the Mannheimer Bahnhof, waiting for the police to show her video sequences from the surveillance cameras. She could best recognize her violin case. She hears the announcements on the platforms, the trains coming to Berlin every hour coming from Berlin. She speaks to people: Have you seen the violin? Students with instrument cases on their back recognize her, have read the post on Facebook. “You’re Anthea!” They call. “And good luck!” Four heavy men with shaggy beards consider how much beer they could buy from reward.

Three hours later, a policeman finally has pity. Kreston is allowed to watch videos from the surveillance cameras with suspects from the police. Slow motion, people get out, people go over the platform, disappear from the field of view of the camera. Kreston did not discover her violin case. The police suspect the thief could put the violin in a suitcase. A good dozen of the travelers’ bags, backpacks, and suitcases, which would rise from the ICE 279 from Berlin to Basel on June 14 at 1:30 pm in Mannheim, would have been large enough to hide a violin case.

There is also an angle that remains hidden from the cameras. If the thief knows the station, he could have left the train without a camera. If he had prepared himself this well – a thief who had planned.

In the meantime every violin maker, every single person in the small music world, knew that Anthea Kreston, second violinist in the Artemis Quartet, had reported her Carl Becker of 1928 as stolen. In the case of theft of expensive instruments, it is like a work by Picasso and Van Gogh: It would only sell under the table. To collectors who put the picture in a vault to bring it out in a solitary moment. Or to people like a British violist, told by Gregory Sigl, who stole the instrument from a concertmaster to play in his cellar. Until he died.

If her violin had disappeared in a vault of an Asian businessman with a love for rare instruments, like the cello of the Italian violinist Domenico Montagnana, the “Sleeping Beauty” on which the Viennese cellist Heinrich Schiff had played, Kreston would probably not see her violin again.

After a few days she gets a call in Berlin. The Mannheim police. A violin maker in Bad Wurzach, Wuerttemberg, has returned her violin. Carl Becker, 1928, light wood. A young man, barely twenty years old, had come to the shop: he had said he had found the violin, and would like an estimate of the worth.

Perhaps the young man was an occasional thief who had risen to the train in good luck in Mannheim, grabbed the closest thing, and left again before the train started. Maybe the next day he saw one of the papers with the reward that Kreston hung around the station. Or read the post on Facebook. Maybe he was frightened then. With a little bit of wood in a shabby box, he had a gigantic problem. The prosecutor has not yet prosecuted the young man, the investigation has not been completed. The crime scene was an ICE on the way from northeast to south-west, the file travels through Germany, the witness behind.

Kreston has sought her precious violin, but found something else essential. It must have been in Freiburg when they approach the last bar of Dmitri Shostakovich’s fifth string quartet on the borrowed baroque violin. It is an untypical conclusion for Shostakovich, not riot, rhythmic, but somehow thoughtful. Ecki nodded to her, Vineta smiled, barely noticeable. Gregor’s gaze, deep as always. The music is tender until it is gone. Anthea Kreston looks into the faces of her colleagues and knows she has arrived.

Comments