What musicology is for in 2016

mainA round robin from William Cheng, of Dartmouth College:

Dear colleagues,

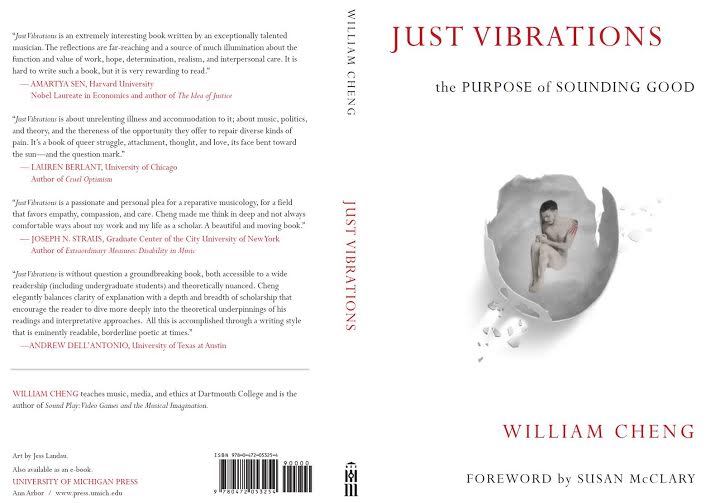

I write to share news of the release of Just Vibrations: The Purpose of Sounding Good (University of Michigan Press, 2016, foreword by Susan McClary). Taking aim at the elitist, antagonistic, and imperialistic dimensions of classical music scholarship and beyond, this book advocates for a care-oriented musicology—namely, for a musicology that upholds interpersonal care as a core feature (rather than merely extracurricular option) of our everyday work.

And you thought it was about understanding the history and meaning of music? How very quaint.

Aside from arguments for or against cultural Marxism this is sad, very very sad.

Very sad.

Music criticism could be argued to be the most self-evident phoney profession since witch-pricking, even though no innocents are killed in the process. Along with the work of the musicologist, music criticism is for me a phoney activity practiced by phoney professionals.

Do I detect the pen of Hans Keller here?… Indeed, and well said.

Frederick,

There is a conceptual distinction between a musical score and the intuitive expression / understanding of the music.

I think people with more or less functional nervous systems know a HUGE AMOUNT about music. We just don’t know how to talk about it.

I thinks nervous system is functional and having taught in a high performing school which had sent over 25 pupils to prestigious institutes and music colleges I can be satisfied that I must have known a bit about the subject. Nevertheless, that doesn’t mean that I felt I had to take any notice of any of these phoney professions and it hasn’t had any lasting effect on either me or my students. Each to their own of course.

Please enlighten me: what on earth should Karl Marx have to do with any of this?

Don’t criticize what you can’t understand–let alone what you haven’t read.

A red traffic light warns for collisions if ignored, you don’t have to try it out. This short recommendation gives-off enough warning signs to know that it is Crazy Musicology again, especially if McClary provides the foreword.

Classical music is NOT about social engineering or PC culture, and the efforts to force the values embedded in the art form into a prefigured mould defined by extra-musical considerations, is politicizing music, like what happened in Soviet Russia or Nazi Germany.

Never trust a musicologist who claims Beethoven IX’s first mvt is about rape (McClary).

People who imagine that musicology is characterized by ‘elitist, antagonistic, and imperialistic dimensions’ probably failed at some exam, and like to parade their flaws as assets.

There are a couple of wonderful pieces by Phil Ford and Jonathan Bellman about “mad studies” and advocacy on their blog “Dial M for Musicology.” Worth a read if you’re interested (re: Crazy Musicology, disability, etc.):

https://dialmformusicology.com/2015/12/27/mad-studies

https://dialmformusicology.com/2016/01/03/mad-studies-and-advocacy

Best,

Will

Will,

thanks for the book and thank you for the informative follow up links. I look forward to reading your work before having an opinion on it, and I think you should take neo-marxist as a compliment.

Hilarious! But if you have seen cases of real depression, autism and insanity from close, you know for sure these have nothing to do with identity and are disorders, resulting in severe suffering. The French philosopher Foucault compared prisons with the incapacity to understand ‘otherness’, so this crazy spilling over the boundaries of intelligence has now also incurred in musicology. The disadvantaged minory of ‘new musicology’ are indeed comparable with patients suffering from mental disorders, turning their isolated suffering into an identity and then claim a place in the field. We live in interesting times.

Calling people you disagree with, “mentally ill”… Now, where have I heard that again…

Oh… that’s right: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Degenerate_Art_Exhibition

Will,

Have you ever read Vladimir Jankelevitch’s “Music and The Ineffable”? Here is a 2004 book review. I agree wholeheartedly with everything said.

Vladimir Jankelevitch makes a distinction between what is ‘untellable’, unable to be spoken of because, as in the case of death, ‘there is absolutely nothing to say’, and the ‘ineffable’, which cannot be explained because there are infinite and interminable things to be said of it’.

Music, he argues, embodies the qualities of the ineffable: it creates a kind of enchantment that bewilders the mind and puts it at a loss for words. Of course, that music is a thing of mystery and wonder that eludes the grasp of words is a truism to which we all pay lip service. We all know that music is radically other to the words with which we approach it, and yet, in our busy professional lives, where music becomes the object of our scholarly enquiry, we work as if that were not so. To be sure, we may produce valuable and fascinating work — as history, criticism, theory, philosophy, or analysis. But somewhere, like a ghost in the machine, the music haunts such systems to which it remains perpetually elusive.

Jankelevitch speaks to anyone who has once had a sense that, were we able to step off the professional merry-go-round for a few moments, all our theoretical discourses around music add up to a kind of avoidance of something more urgent, a way of holding music’s power at arm’s length, an ordering in rational networks of what might otherwise be too disturbing. He is surely right that the rush into hermeneutics of any kind (amateur or professional) expresses a kind of anxiety — a refusal of the music, a fear of allowing it to persist on its own terms, a compulsion to render it safely into the verbal.

At the very least, when confronted with the degree to which music exceeds the ways in which we frame it, we have perhaps lapsed into despondency, surviving only by separating out our professional writing and our ‘real’ (private) experience of music. For that reason alone, his book should speak to many of us.

In essence, the book reads as a single poetic-philosophic meditation on a single theme — the ineffability of music. As a topic this is both profound and banal at the same time, and therein lies the productive difficulty with the book. On the one hand, it tells — once again — that we cannot talk about music. More precisely, it opposes the way in which music is appropriated by analytical and discursive practices that remain always outside its substance. It does so, however, in such a compellingly beautiful and intellectually inspiring manner that it revivifies one’s capacity for both thought and feeling in relation to music. In this way, it provokes thought about music while at the same time appearing to undermine it. It thus joins a select history of great writing on music that tells us — compellingly — that there can be no great writing on music.

The first line of Carolyn Abbate’s introduction sums up the matter nicely: “Music is no cipher; it is not awaiting the decoder”

Music is not, argues Jankelevitch, amenable to hermeneutics. He forces us to question the discursive framework through which we attempt to speak about music and to make that hubristic claim — ‘to understand music’. He insists that all the terms with which we attempt to grasp hold of music are always and only metaphors and analogies, redrawing the lines between the ungraspable nature of music — resistant to logical schemes at every turn — and the structures in which we seek to ‘make sense’ of it. The language of music theory, whether in aesthetics or analysis, is spatial not temporal.

In the same way, Jankelevitch argues that music is not a discourse and that the idea of development, a process of thought unfolding through time, is misplaced in relation to music. References to development are, he says, merely ‘manners of speaking, metaphors and analogies, dictated to us by our habitual discursive ways’. For Jankelevitch, there is nothing in the music ‘to be understood’ and he pours scorn on the idea that the music can be ‘followed’, as in the tracing of a succession of themes. He has no time for technical analysis, which he characterizes as a resistance to the music’s enchantment, an activity that is both ‘manically antihedonist’ and yet frivolous at the same time. It is the separation between the hermeneutic act and the music that Jankelevitch takes issue with. Thinking about music, in technical analysis or in other discursive forms, entails a separation from the music that makes the music peripheral.

So much of what he says disturbs the comfortable state of musicology (old and new alike), an effect he achieves because he upends complacencies hard won through years of disciplinary servitude”. His accusation that what we [musicologists] do falls short of the music should be welcomed with penitence; he voices our own, usually unspoken, anxieties. His book brings “our failures home to us

————-

Jankelevich is not a musicologist, as far as I know, but a philosopher.

There is nothing wrong with analysis of the blueprint of music: the score, as long as the analysts are aware that the music only really exists when performed. The score is an abstraction which comes to life when read in the imagination, and when performed in the real.

But, traffic lights are microaggressions. They represent the oppression of woman, minorities, and the poor by the white male straight majority.

That’s a good one…..

Traffic lights were invented by an African American, Garrett Morgan. Are you insane?

Well-said John.

John:

I have been asking myself why it is that the obvious trolling behavior by the Chorus of Commenters that hang around _Slipped Disc_ still upsets me, even though I am used to it, and even though, as David Josephson is right to point out, there is nothing really to be done about such trolls other than abstain from feeding them.

I think it is because the trolling is done in defense of “classical music,” a cultural formation around which I built a significant part of my own identity, and thus these trolls implicate me more directly than those from the alt-right who fetishize, say, white nationalism and anti-liberalism, things I never identified with.

Maybe this, not the smallness of our field, is why ideological disputes within musicology have raged with such bitterness over the years. We all like (some of) the same music, most of us identify with (some of) it and thus, by the rule of elective affinities, we feel that we all ought to think the same way about it, and also about life in general. When we, as is inevitable, discover that we *don’t* think the same way, the feeling of betrayal can be as keen as with infidelity in a spouse.

I had my come-to-Jesus moment regarding the divergence of ideologies among classical music lovers long ago when I watched my beloved Furtwängler conduct before a hall full of Nazi officers, among them luminaries like Goebbels and Goering, the kind of dismay I felt when I learned that an otherwise brilliant man like Heidegger was an enthusiastic supporter of the Third Reich. Loving Schubert and Beethoven does not ipso facto make you either a good or an intelligent man, as is obvious by some of the comments here, or Cheng and McClary themselves.

G.P.

Earlier you wrote.

“We have a saying in French: “La musicologie est à la musique ce que la gynécologie est à l’amour” — musicology is to music what gynecology is to love. The bottom line is, if the mysteries of what makes a great composer could truly be unveiled, music composition would become a clear and discernable method, and we’d have a lot of geniuses out there. Perorating for hours on end about music may be all well and good, and there might even be a place for it somewhere, but it still remains that most musicologists, in their entire lifetime, will never be able to write a single bar worthy of Debussy’s work nor, I suspect, perform a musical line on a real flesh and blood instrument in an acceptable and appealing fashion. Music is meant to be experienced first-hand — not theorized about in the antechamber of musicological salons or colloquia.”

—————–

What both of these disciplines have in common is that after the real-world application, the human has the urge to talk about it, to savor it. We have evolved to this state.

A woman incapable of lovemaking until the gynaecologist has wrought his/her expertise understands the true meaning of the glib old canard, and you can be sure they both will discuss all these aspects afterward. As for musicologists, they are not critics, nor are they composers or performers (usually, but there are famous exceptions). They are musicologists. They have their place and their purpose. (You seem to be confused about what this entails.) If a great chef cooks a wonderful meal and no one eats it nor can discuss it, is the chef still an artist? If a great violinist plays a concerto while suffering an attack of loose bowels, what does he talk about afterward? Surely not elevated discourse!

Why not try the real world, for a change.

Would someone care to explain what “a care-oriented musicology—namely, for a musicology that upholds interpersonal care as a core feature” means without using psychobabble or in-group jargon?

A “care-oriented musicology” is a way of transferring musicological knowledge from lecturers to students in an intimate way, through fondling, taking students on the lap and whispering Schenker’s secrets in the young and innocent ear, and taking them (the students) out privately to cinemas, luxurious suppers in 5 star restaurants sprinkled with red wine, and finally taking the student to the lecturer’s home to expose her/him to Beethoven IX’s first mvt and loudly read McClary’s analysis to her/him, and then – here sinks the curtain of discretion over the proceedings.

I would wish some ‘curtain of discretion’ would have sunk before you wrote this contribution.

Then you should certainly avoid “Just Vibrations: The Purpose of Sounding Good (University of Michigan Press, 2016, foreword by Susan McClary).”

Hi John Borstlap,

I read your comments and was extremely curious about who you are, and so I googled you, and I found out that: “Although born in the Netherlands, his music is rooted in the German classical tradition, the countries being very close.”

http://johnborstlap.com/biograhy/

Well, that seems about right, more or less.

How terrible to be a neo-marxist. While most of us hear music, they hear sexism, racism, and class struggle. They miss all the joy of life because all they can see is politics.

Bringing the problem right to the point. To be able to exercise neo-marxist musicology in the first place, means the complete absense of musicality and interest in music as such.

I wish more musicologists and their students would follow Mr. Kramer’s advice.

“All music trains the ear to hear it properly, but classical music trains the ear to hear with a peculiar acuity. It wants to be explored, not just heard. It “trains” the ear in the sense of pointing, seeking: it trains both the body’s ear and the mind’s to hearken, to attend closely, to listen deeply, as one wants to listen to something not to be missed: a secret disclosed, a voice that enchants or warns or soothes or understands. This kind of listening is done not with the ear but with the whole person. It is not the result of learning a technique (the stuff of the “music-appreciation racket”) but of adopting an attitude. It is not a passive submission to the music but an active engagement with it, a meeting of our ability to become absorbed — sometimes for just a few moments or even less, sometimes for hours on end — with the music’s capacity to absorb us. In attending to classical music, we also tend it: we tend to it and tend toward it, we adopt and argue with its way of moving and being. We dwell on it by dwelling in it. We don’t simply realize something about it; we realize the music in a more primary sense: we give it realization, as one realizes a plan or vision or a desire.”

No idea who Kramer is but he seems to miss out the sheer enjoyment of listening. This quote sounds like some sort of evangelical sermon.

No, the text is about engagement, which inevitably includes enjoyment. But classical music is not entertainment, which is an engagement with a more narrow range of stimuli – nothing wrong with that. Classical music also offers entertainment, but merely as a part of a much wider range. The quote is very apt, and when such listening is cultivated, it transforms the listener.

Thank you Lynn, for posting this.

Lynn — do you have a source for this quotation? I haven’t been able to locate it in what books by R. Kramer that I have on hand or a google search, so I’d be grateful if you could post it.

Benjamin,

It can be found on page 7 of his 2007 book “Why Classical Music Still Matters”

Thanks! I should have known it was L. and not R. Kramer.

Same question as above: why do you believe Karl Marx has anything to do with this? Or are you in fact referring to Groucho? And if so, why he?

In his ‘Music Science and its Malcontents’ (1843) Marx explains the suppression of dissonances by a triadic elite, and predicts the rebellion of dissonances and the overthrowing of the triad after some 100 years. That happened somewhat earlier, at the beginning of the 20C. He especially took offence at the eternal pressure from the elitist triads that dissonances should resolve, without the freedom to unresolution or simply wandering around in tonal space. Adorno took-up this line of argument and described Schoenberg’s liberation (’emancipation’) of the dissonant as the beginning of mature new music, and in the same time proclaimed the ugliness of the results as the true face of the nature of the tonal proletariat, which we should embrace as social truth if we ever would want to achieve serious music with real justice for all the notes.

This is pretty, pretty, pretty good, pace Larry David. For a minute you had me wondering whether you were quoting an actual work. Develop it some more and I bet you can get some reputable academic journal to publish it.

I am sure the time will soon come where the playing of certain parts of the western canon will be considered too traumatic for students to be subjected to without “trigger warnings” How can one subject an assault victim to a Beethoven Symphony in which a main them symbolizes “rape” as posited by the esteemed professor Dr. McClary. No Beethoven and the rest of those male paternalistic capitalist must go!

If you think this notion is absurd or paranoid, then read about the University of Wisconsin that removed a historic painting from a common area because it depicted early American fur traders with Native Americans as subordinates in their hunting activities. The university wanted a safe place for its sensitive students

How can one argue that this one piece of scholarly work represents the state of musicology in general?

This type of argument is synecdoche.

Anyone interested in the actual text of the book, and not content to literally judge it by its cover, can find it free and legal at the link below. Judging and drawing conclusions based on assumptions and outward appearances being things the disability-rights movement have revealed as problems, incidentally.

http://quod.lib.umich.edu/u/ump/14078046.0001.001

No normal disabled person screams its own recommendation in public space as the book does.

Let’s problematize that word “normal”, shan’t we?

You read that book really fast.

When you sniff at the cover, its fumes expose its contents.

Susan McClary again, that feminist musicologist who hates classical music with a vengeance and can’t stop spreading her militant feminist nonsense .

Add Mr Cheng now to these enlightened forces…I guess he is an honorary feminist.

And just for the record: neomarxism isn’t a compliment really, just in case some salon marxists conveniently forget that other big holocaust in 20th century, where a fellow called Stalin killed 20 millions under the spell of that ideology.

Pierre, I’m grossly insulted by your reference to me as an “honorary feminist.”

I’m a feminist, period. (Or at least I’m learning to be, best as I can.)

My final comment here, for my own peace of mind 🙂

Brian Klocke writes: “Although I believe that men can be pro-feminist and anti-sexist, I do not believe we can be feminists in the strictest sense of the word in today’s society. Men, in this patriarchal system, cannot remove themselves from their power and privilege in relation to women. To be a feminist one must be a member of the targeted group (i.e a woman) not only as a matter of classification but as having one’s directly-lived experience inform one’s theory and praxis.”

By this standard, Will Cheng CANNOT be a feminist.

http://nomas.org/roles-of-men-with-feminism-and-feminist-theory/

Does this now mean that we must be subject to Mr. Klocke’s beliefs (since he has defined his position as based on a belief and not a fact)? It’s fine that he believes this, but do you really think he gets to define who gets to claim feminism for themselves? And why? And why should it matter to you anyway?

Hmmm I find in strange that one considers neo-marsism a bad thing. Not being a “salon” marxist, as I believe Mr. Boutry is; good ol’ Karl and Fred have rolled over in their graves as they would not have wanted their ideas grossly perverted by the hands of fascists, dictators, or totalitarian regimes. Very anti-marx-engels. It’s almost like saying the United states a democracy… but ultimately it is a corporate oligarchy where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer… an idea marx-engles were acutely aware of. Two radically different concepts. And to finish my diatribe, I highly doubt that musicology will kill millions of people.

Josef, you are right on! Thank you for your insight.

I was just talking about the nutjob who suggested the recapitulation of the first movement of Beethoven’s 9th symphony symbolized rape. Thanks to the comments above, I now know the provenance. I’ll close by saying, you can’t rape the willing. And when it comes to Beethoven, boy, am I willing.

Chapeau.

I reached this nauseating thread through the AMS discussion list. I find it truly astonishing that Mr. Bortslap can argue so viciously against a book he hasn’t even bothered to read. What intellectual sloth.

I always admired Adolf Hitler, and could not understand why he hated the Jews so much and why he would start a world war to make his point. My intellectual friends were quite shocked when I brought this up in conversation, once in a while, and mostly they hurried to the hall to get their coats and hats. When I asked one of them, at the gate, why this man was so bad, his ‘Mein Kampf’ was mentioned, a book I had never heard of before. Had he read it? ‘No’, was the answer, ‘ but that’s not necessary’. That seemed intellectually flawed, so I went to the bookstore in the village to find his ‘Mein Kampf’. The poor lady got quite pale in the face, worked me out of the shop and closed it immediately. I went to London and searched for it in 34 book stores, but was only met with contempt, and from the 29th shop onwards I was continuously followed by two man in long rain coats. On the internet I could not find it, and one time when I thought I had caught a well-thumbed 3rd hand copy offered by a German site with hughe swastikas at the top, I was blocked. After calling my aunt in Berlin, I went to Germany for a week and vainly tried to find the tome in well-served book stores in the capital, and in Hamburg, Frankfurt, Meissen, Munich, and Obergau, and finally I got an old fellow talking late at night in a Kneipe in Ulm, who knew an old woman down the street who was suspected of possessing a copy. The next day he handed me a closed bag with the book, looking around anxiously, and asked me 200 EU for it. Back in the train I began to read, it’s really well-written and full of exciting ideas, but on the train from Dover to London I reached the back cover and understood why he had to go at such length to make his point. Very sad! From that moment onwards, I did not like Hitler any longer. For that reason, I can only recommend everybody to always read every book book which has been reviewed, described, mentioned at tea time, subjected to mythology, etc. etc. before forming an opinion, however modest. I heard that Christianity had organized something called ‘Inquisition’, so next week I will begin to read the Bible, and after that, – sorry, my PA calls me.

So, are you saying I can skip “Mein Kampf”? ‘Cause I always suspected I may not enjoy it, what with half my family being murdered by the Third Reich and all. And yet, I did always have this nagging doubt that perhaps I hadn’t given Hitler his fair shake.

That’s the problem, isn’t it? People write so much! How to get through all of that? Maybe there should be a government institution to take charge of that.

To people who complain about those of us who will NOT read such tripe, considering who wrote the introduction (not to mention the claptrap of the blurb): To know that, say, David Irving wrote the introduction to a book about the Holocaust, that would be more than sufficient to render such a book unreadable. Any book introduced by McClary is bound to the same fate.

Wow, GP Blessing. I’m no expert in the art of persuasion, but I’m pretty sure comparing one of the most celebrated (and, as evidenced from your comments, *still* wilfully misread) scholars in musicology to a holocaust denier…is maybe not the most effective way make people sympathetic to your point of view.

Oh, dear. “Celebrated”? By whom? I mean, Donald Trump is “celebrated” in certain quarters. I think it is rather important to know *who* is doing the celebrating here. As for the analogy you find indelicate, the intensity of my revulsion as a music lover toward McClary is at least as great as that which I, as a Jew, feel toward Irving. I understand that you may feel otherwise, to the extent that I understand many Trump supporters would find David Irving quite compelling.

Your revulsion towards someone who wrote something 25 years ago that had a few paragraphs that were critical of a composer you like (and which I’ll wager you never actually read) is “as least as great” as your revulsion towards the guy who’s made his career out of denying the genocide of 6+ million people?

Got it.

Have indeed read & find her appropriation of music to score political points & further her ideological agenda utterly repulsive, on the same level as what the Third Reich tried to do to the entire Germanic musical Canon. She’s a demagogue & a charlatan as David Irving is one. And yes, for me music is as serious as, more so, even, than religion.

As a former student of Susan McClary when she was an instructor at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis East Bank Campus in the early 1980s, I can aver that she was a capable teacher, one who encouraged discussion of relevant topics and recognized scholarly research.

That said, when she published “A Molestation Instead of Music” — er, ‘scuse me, Feminine Endings, or at least as much as I could stand of her silly theses about Beethoven, I had to scratch my head and say, as Kal-El did so often, “What th–?”

It is often, I feel, the job of the student to contradict the teacher, and in this case I shall happily provide an alternate interpretation of the passages in the Ninth Symphony that Susan called “the throttling murderous rage of a rapist incapable of attaining release.” Beethoven was by all accounts lacking in basic social skills, it is true, but it is difficult for me to square the idea of Beethoven as rapist with the Beethoven who worshipped his Unsterbliche Geliebte, the Beethoven who seemed to treat his female friends and acquaintances no worse than he did the males, and most of all the Beethoven who elevated the faithful and forceful wife Leonore to the iconic status of savior. The evidence for “Beethoven the rapist” is, I am afraid, lacking.

We do, however, have evidence of a condition, or rather conditions, that Beethoven is known to have suffered from, which might have been reflected in those outbursts in Op. 125. I refer, of course, to his alternating episodes of constipation and diarrhea.

Needless to say, since this theory (which I admit I postulate only as a vague possibility, leaving further investigation and publication as the province of some hopeful grad student yet to come forward) does not have any political agenda, I fear that it would find difficulty finding currency in the “new musicology” of the day.

(Oh, and in case anyone is wondering, I came through Susan’s seminar with flying colors.)

You know, if Suzy had used her “reading” of Op. 125 1st mvt. recap as a metaphor for a literary and/or political exegesis, I’d not find it (quite so) reprehensible. It’s rather cute to use the whole tonic – dominant/subdominant, primary/secondary theme & sonata form as a whole as a metaphor for “patriarchal structures” and what not, but where Suzy loses me, and I suspect many others, is that she finds all this as being somehow *inherent* in the music, or at the very least latent and furthermore an instrument to shore up tyrannical patriarchy. As you say, what the -? It’s quite hypocritical, also, for the radical left to complain about cultural appropriation, when such is part and parcel of their project to appropriate Western music, art & literature to further their political ends. Whether the right or the left tries to do it, art in the service of politics can never come to any good.

Indeed. But leftish thinking often suffers from confusion of contexts, like Foucault comparing a handwriting manual with supporting straight lines (to get the letters nicely regular) with military drilling, and the prison system with excluding ‘otherness’ in society. This confusion created the ‘Aha-Erlebnis’ with lots of people feeling incarcerated within the disciplines of their profession, and happily spilled observations from one field into another, like multiculti cooking.

Ahem. Not all leftists.

Most of the commenters here are not engaging in some measured critique of Will Cheng’s book. The majority of comments come from people who admit to–and indeed boast about–not having read Just Vibrations. A sampling of recent entries reveals much worthy of the igniferous adjectives in question:

1. Several comparisons of scholarship from Cheng (and others, inc. McClary) to Nazism, Mein Kampf, and in one particularly noxious thread, the work of a prominent Holocaust denialist.

2. Numerous assertions that what Will is doing (and by extension other musicologists working in non-traditional areas) is not only bogus, but categorically not musicology. Compounding this are insinuations that engaging in non-traditional musicology means that one does not care about music.

3. An insulting and I suspect deliberate misspelling of Will’s surname as “Chang,” followed by an update that further botched his name as “Chaeng.”

4. Mocking, willfully obtuse references to microagressions, trigger warnings, and a general mean-spirited dismissiveness towards any effort to instill a culture of empathy in academia.

5. This comment — “If you are so concerned about the safety of female students, why are you a musicologist? Why aren’t you a policeman or a rape counselor?”

I see nothing censorious in pointing out how heinous this is.

I suppose it’s easy for some to disregard these posts as nothing more than the uninformed feculence that tends to accumulate in internet comment sections. And perhaps we are better off simply ignoring it. But let us not miss one of the most valuable messages of Will’s work: this sort of “trolling” still has the potential to wound deeply, even when its spewed by total strangers. Ignoring or brushing it off is not always an option. Some of us really do have skin in this particular game. I find it particularly contemptible that the views on Norman’s blog might belittle or discourage scholars–esp. junior scholars–who pursue topics that do not fit within the borders of musicology-as-traditionally-defined. Absolutely nothing is gained, and so much lost, when we rigidly police who gets to call themselves a musicologist.

I’m honored to have received special mention in your oh-so-micro-agressed and triggered tantrum. I make no apologies for drawing an analogy between McClary and Irving, for they both employ shoddy scholarship in the service of an ideological agenda. If the shoe fits…

I see that Mr. Cheng has found a receptive audience in repositories of PC-speak such as the Huffington Post. While he can expect to get away with BS that has nothing to do with music before such an ignorant audience, he can similarly expect – and rightfully so – to be eviscerated in a forum such as this, where the interlocutors are rather more knowledgeable about the subject matter. If he can’t stand the heat, then lucky for him he doesn’t teach at the University of Chicago.

Finally, you refer rather comically to “trolling”. If anyone is guilty of such, it is the likes of Cheng & McClary, who troll – in the guise of academic discourse – the music of dead, white men who are obviously powerless to defend themselves against their vulgar verbiage. Do not be surprised, then, that some of us may be “triggered” into defending the otherwise defenseless. One can only imagine the ridicule and humiliation to which Beethoven would subject McClary, Cheng and their ilk. I suspect my own invective would seem positively meek by comparison.

While Jankelevitch certainly is on much firmer ground to wax lyrical regarding the ineffability of music – as opposed to speculating whether Beethoven meant to express in music his frustrated rape fantasies – I do think it’s not entirely accurate to suggest “absolute music” is totally and completely subjective and that we’re incapable of saying anything substantive about it. To say that such music is indeed irredeemably subjective gives license to intellectual rapists like McClary and Cheng to propose their otherwise absurd hypotheses without anyone being able to have a basis on which to contradict them. However, we know that Beethoven, for instance, had some pretty specific ideas in mind when he composed pieces like the Eroica, which he himself titled, the Pastoral, whose individual movements he likewise gave titles to, or his “Heiliger Dankgesang” from Op. 132. You can’t refer to the latter, then, and claim that it has nothing to do with anything other than just being a succession of notes that reference nothing other than themselves. I know some music-lovers refuse to accept that music can have any “spiritual” content whatsoever, and for them, obviously, the “Heiliger Dankgesang” must be utterly alien and inscrutable. For Beethoven himself that movement, among others, was replete with extramusical meaning, and we know it was because he very specifically told us so. There are other examples where, even though Beethoven did not leave us any verbal crutches on which to stand, there is near universal agreement regarding the extramusical “meaning.” The arietta of his Op. 111 comes to mind: Save for a handful of contrarians who refuse to hear anything other than adagio molto semplice e cantabile, pace Toscanini, few who hear that movement are not moved to identify in it the suggestion of an otherworldly realm, particularly in the latter variations so suggestive to many, if not most, listeners of the twinkling of stars. Of course, like William James would argue in his “Varieties of Religious Experience,” you may “hear” a Christian heaven or a Buddhist Nirvana or a Norse Valhalla or whatever referent you may project onto the music on the basis of your personal background, but that what is being conveyed by the arietta of Op. 111 is indeed a “religious experience” is an assertion that finds near universal agreement (without having read a word about it, when I first listened to Op. 111, I knew I was listening to a work that was in every way a “spiritual” testament – as much as I hate to use such a vague yet loaded term).

Point is, yes, music is subjective, but it is not therefore devoid of meaning nor is it open to an infinite variety of interpretations, all of which have equal validity, no matter how patently absurd. Unfortunately, precisely because it is the most subjective of all arts, absolute music is also ripe for the morally relativistic revisionism of a McClary, because when there are no limits, no consent to a pre-existing cultural and linguistic context within which to “understand” what we are listening to (and yes, music is a language), all meanings and definitions fall apart and everything and anything is permitted.

I suggest that possibly the only people who are qualified to “talk” at all about musical meaning are probably those writers who can make a sort of music with words. I’ve read probably hundreds of thousands of words written about Beethoven’s late quartets, and none have approximated the experience of listening to them as much as these few:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

No offense to musicologists, but none among their number could ever write such words. Similarly, no one can convince me that the Diabelli Variations do not have a very strong “philosophical” content whose main idea is illuminated by Nietzsche’s concept of the Ubermensch, namely, the transformation of a trite, vulgar, primitive little theme into a refined and rarefied menuetto which calls to mind Nietzsche’s seemingly absurd statement that he “would believe only in a God that knows how to dance.” And it is similarly doubtful to me that Nietzsche was not thinking of Beethoven’s music (which we know he adored) when he wrote, “Whoever, at any time, has undertaken to build a new heaven has found the strength for it in his own hell.”

Next to Eliot and Nietzsche, the whining pronouncements of a McClary or a Cheng are relegated to laughable irrelevance.

If it’s so irrelevant, why have you commented so extensively on it? And why have others? And why is the book being debated for weeks, and selling well, and getting so much coverage?

What you’re trying to say is that McClary and Cheng *should be* irrelevant; sadly, your *should* isn’t fact. Maybe if you took time to read “Just Vibrations,” you’d see that Cheng quotes Jankelevitch in the introduction? And if I recall Nietzsche as well, and praises Beethoven among other music. Sooo….yeah.

This is one of the most shameful comment threads I have read on the internet in a long long time, and boy is that saying something. At least on reddit and other awful websites, the participants usually don’t make pretenses to scholarship and expertise.

I hope Mr. Lebrecht had higher aims in mind when he started this blog. It does not reflect well on the world of classical music.

Daniel wrote:

“This is one of the most shameful comment threads I have read on the internet in a long long time, and boy is that saying something. At least on reddit and other awful websites, the participants usually don’t make pretenses to SCHOLARSHIP AND EXPERTISE”

~~~~~~~~~~~~

But the difficulty with music is that it does not essentially exist in an intellectual construct. True, music has form and that can be analyzed with logic and music has harmony and that, also, can be analyzed within a logic construct but the intellectual analysis of music is most unimportant when compared to the effect music has on our deep emotions. Analysis of emotional content is not unusual but it, ultimately, is little more than the water running off the leaves of trees during a rain; it has little effect on the leaves and it is not a primary source of nourishment for the tree.

Putting a name to something may make it easier to spot and recognize (the musicologist’s point of view), but it does not mean that it suddenly changes whatever it was before you could describe it. Sometimes yes it can help to speed up the process but it does not mean that things like bias disappear. Musicians and musicologists can be just as biased and short-sighted as “lay-listeners”. Also, knowledge of music theory or the ‘instruction book’ is not the basis for aesthetic experience. What it describes is, but theory is the description, not the object. We still have the object without the technical data. We still have ears and we are still fully equipped to hear it. I don’t think it deepens understanding of what the music expresses on its own terms which is greater than its own formal content.

Music affects us much as the sense of smell influences us. It speaks directly to the emotional content of our lives. It is the art the does not require any understanding, explanation, nor analysis. All of these things can add to the art of music but, ultimately, they are little more than rain on the leaves.

One brute fact often overlooked needs to be forced upon our consideration: most works of art are more or less intelligible and give pleasure without any kind of historical, biographical, or structural analysis. In the end we must affirm that no single system of interpretation will ever be able to give us an exhaustive or definitive understanding of why a work of music can hold an enduring interest for us, explain its charm, account for its seduction and our admiration.

Listening with intensity for pleasure is the one critical activity that can never be dispensed with or superseded.