‘Beethoven grabs you by the collar; Schubert leads you by the hand’

Why BeethovenThe pianist Jonathan Biss, in a New York Times essay, attempts to delineate the impact on a performer of playing the late works of the two great Vienna contemporaries.

He does so in an attempt to argue that Schubert, rather than Beethoven, understands loneliness to its core and can help us out of isolation.

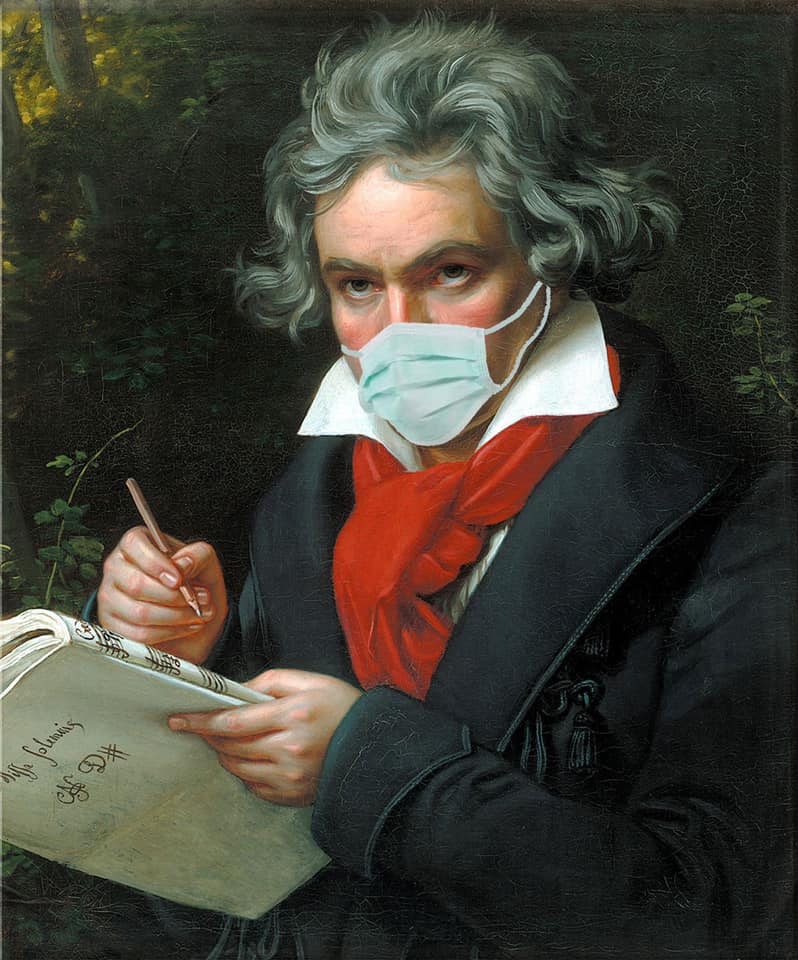

I’m not so sure. In my book Why Beethoven, I described how Beethoven, more than any maker of music in any age of history, exemplified the situation imposed on many of us during Covid-19 – confined to our houses, separated from loved ones, denied the touch of a friendly hand, alone as never before. And how, in this confinement, Beethoven in his late sonatas and string quartets, found a path out of his enclosure in deafness that helped him and us to believe once more in the redeemiung power of art.

Biss writes: Loneliness is universal; paradoxically it is a shared part of the human experience. Schubert knew this, and had the gift to convey it in sound, sometimes with profound sadness, but never with bitterness. Schubert’s heart remains open, ready to be broken anew. If you feel alone — because of holiday anxiety, or political uncertainty, or life circumstances, or simply because you are a person — I implore you: Listen to Schubert. He offers his soul to the listener, without armor or guile. He is our best friend.

There is a case to be made for both composers, and for others. Schubert may be one person’s remedy, perhaps in acute situations. I find the Beethoven effect functions more efficaciously across time.

Comments