‘Thin, dull and obvious’ – Alastair Macaulay’s verdict on the Royal Ballet’s Maddaddam

balletOur renowned ballet reviewer had an unusually bad night:

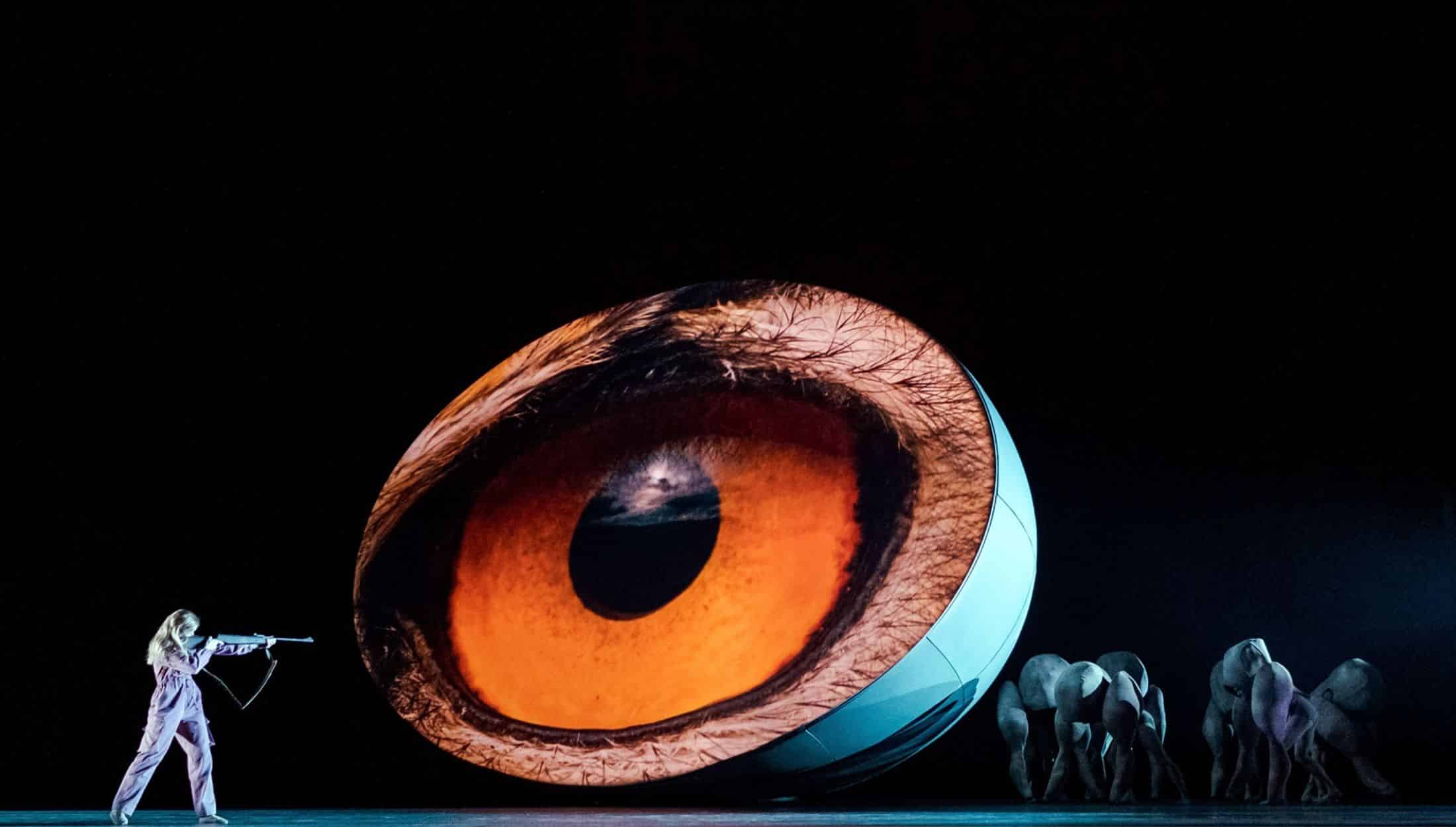

MaddAddam, Wayne McGregor’s Timidly Clichéd Dystopia

by Alastair Macaulay

In Wayne McGregor’s new three-act “MaddAddam”, the Royal Ballet has chosen to present us with the triumph of the inept, the mediocre, and the neo-bland – dolled up as if they were innovative and bold. McGregor made this harmless piece of dreariness two years ago for the National Ballet of Canada, and yet the Royal at Covent Garden has chosen to import it. “MaddAddam” is Dystopia Without Tears – safely distanced from us so that we can watch its postapocalyptic visions without feeling they come near us, even though such words as “pandemic” are bandied around – a cartload of safely “modern” clichés that takes Covent Garden to a new low of tedium.

On the most obvious level, “Maddaddam” is crummy at conveying its scenario, which tries to conflate three dystopian novels by the Canadian novelist Margaret Atwood (“Oryx and Crake”, “The Year of the Flood”, “MaddAddam”). Even though it resorts to the most heavy-handed non-dance narrative devices (spoken narration, titles in neon, videos of marches and fights), the overall storytelling by McGregor and his regular dramaturg Uzma Hameed is neither clear nor interesting. We can argue about how good a writer Atwood is, but certainly her fiction is characterised by degrees of tough-minded wit that McGregor and Hameed entirely fail to echo.

Worst, the commissioned score for “MaddAddam”, by Max Richter, is shockingly thin and dull and obvious – the kind of cliché-heavy twaddle that one would never expect to find from any music theatre with serious standards. Richter uses radio distortion (in the way used by John Cage and colleagues forty years ago) as a dystopian overlay above obvious, tonally safe, tritely scored musical patterns: conventional four-note sequences slowly rise or fall, a squillion times. Much of this is taped, and much heavily amplified. How conductor Koen Kessels is still awake by the end is his secret.

All this might be tolerated if there were some serious dance-making going on here. McGregor, a modern-dance man who moved to ballet decades ago, has shown himself capable, in a few other works, of subtlety and rigour. Most of the dances of “MaddAddam”, however, look like bad imitations of McGregor style at its most tritely flashy. Heads suddenly jut forwards. Legs are almost invariably extended above hip-height (and often past six o’clock splits). Torsos tilt earnestly forwards beneath the level of the pelvis. (Act Two has brief moments, when McGregor briefly employs dynamic contrasts, suddenly making the dancers looking fresh and sincere. They don’t last.)

On top of this, McGregor piles on innumerable standard ballet clichés. How many spinning chaîné turns across the stage do we see here? how many attitude turns? how many overhead lifts? how many supported grands développés?

The main extra ingredient here, unfamiliar in McGregor’s earlier work, is hammily communicative gesture. As in every other respect, “MaddAddam” here does not do subtle. Arms and hands – whether addressing another dancer across space or cradling another dancer’s face or just indicating pleading or despair – work in the old expressionistic way that was already the most ponderously old-fashioned element of Kenneth MacMillan’s work in the last century.

I don’t believe that McGregor is invariably the cliché-monger that “MaddAddam” makes him seem. But he’s been resident choreographer to the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden for eighteen years. It’s a marriage that’s turning him and the company into their lowest common denominators. “MaddAddam” is the latest and feeblest work in which he has been trying to fit into the Royal Ballet mould of three-act storytelling while seeming to update it. Sure, Atwood dystopianism is a new vein for a ballet company that still spends much of its time on the nineteenth-century classics – but McGregor’s version of it is tired and timid.

Stuck amid this morass are several of the Royal Ballet’s more remarkable dancers: Joseph Sissens (Snowman/Jimmy), William Bracewell (Crake), Fumi Kaneko (Oryx), Melissa Hamilton (Toby), Lukas Bjorneboe Brandsrod (Zeb). But none of them are flattered by Lucy Carter’s dim lighting. They do what they can to turn on charm, vulnerability, intensity. Thanks to the choreography, however, even their best efforts look synthetic.

<www.roh.org.uk. In Coivent Garden repertory till November 30.>

Comments