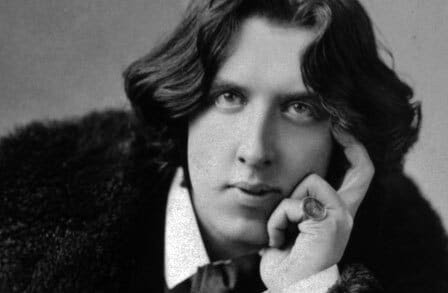

Ruth Leon recommends… Oscar Wilde’s 170th Birthday

Ruth Leon recommendsOscar Wilde’s 170th Birthday

In the West End theatre season of 1895, the playwright Oscar Wilde had three plays running simultaneously in the West End. Lady Windermere’s Fan came first, in 1892, A Woman of No Importance (1893) and An Ideal Husband (1894). He could, it seemed, do no wrong.

And then he could. His private life, which wasn’t very private, and his own hubris, tripped him up. He fell in love with a feckless young man, Lord Alfred Douglas, and this relationship led to a series of disastrous consequences which took him into a catastrophic downward spiral, imprisonment in Reading Gaol, and a solitary death in a Paris boarding house.

This week is the 170th anniversary of the birth of one of our most influential and colourful Irish writers whose profligacy in all ways led to a sudden downfall which nobody could have foreseen in the early years of his unprecedented popularity.

But Oscar Wilde’s talent is still with us in his plays, poetry and other writings. An adaptation of his novel, The Picture of Dorian Grayhas just finished a highly successful run in London’s West End and is about to open on Broadway.

As a reminder of his playwriting craftsmanship, here is the first of his West End hits, a recent production of Lady Windermere’s Fan starring Jennifer Saunders and Samantha Spiro. A comedy of manners exploring the social mores of Victorian high society, the story focuses on young Lady Windermere who suspects her husband of having an affair. Enter Mrs Erlynne, a woman with a past who the chattering classes suspect of being a scarlet woman.

Happy Birthday, Oscar, despite your unhappy end, may new productions of your work continue to influence playwrights forever and may we continue to enjoy them in theatres throughout the world.

Comments