A leading British composer died today

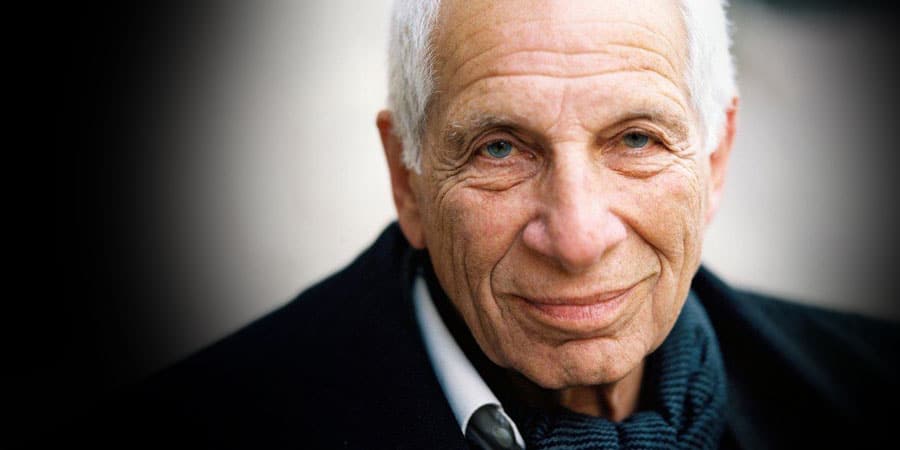

RIPSchott UK have announced the death early this morning of the influential composer Alexander Goehr.

Sandy was 92.

A Hitler refugee, born in Berlin to the Schoenberg-trained conductor Walter Goehr, he studied in 1950s Manchester alongside Harrison Birtwistle, Peter Maxwell Davies, John Ogdon and Elgar Howarth. Goehr brought a much-needed cosmopolitan dimension to the insular group, having also studied with Olivier Messiaen and Yvonne Loriod in Paris.

While Harry and Max achieved international renown, Sandy’s compositions were more intellectual and introspective. They include four symphonies and several concertos. He was rwice composer in residence at Tanglewood. Meanwhile he taught two generations of composers at the University of Cambridge.

Schott release follows.

It is with great sadness that we announce the death of Alexander Goehr at the age of 92. Distinguished composer and teacher, Goehr’s substantial impact on contemporary music in Britain and abroad is perceptible through his significant compositional output as well as the many noteworthy composers whom he taught.

Goehr was born in Berlin on 10 August 1932, the son of conductor Walter Goehr, and brought to England in 1933. He studied with Richard Hall at the Royal Manchester College of Music and with Olivier Messiaen and Yvonne Loriod in Paris. In Manchester, Goehr was a conduit between the recent music of continental modernism and his fellow students, and together with Harrison Birtwistle, Peter Maxwell Davies and John Ogdon, he formed the New Music Manchester Group. In the early 1960’s he worked for the BBC and formed the Music Theatre Ensemble, the first ensemble devoted to what has become an established musical form. From the late 1960’s onwards he taught at the New England Conservatory Boston, Yale, Leeds and in 1975 was appointed to the chair of the University of Cambridge, where he remained Emeritus Professor until his death. He also taught in China and was twice Composer-in-Residence at Tanglewood.

The year of Goehr’s appointment at Cambridge coincided with a turning point in his output, with the composition of a white-note setting of Psalm IV (1976). The simple, bright modal sonority of this piece marked a departure from post-war serialism and a commitment to a more transparent soundworld. Goehr found a way of controlling harmonic pace by fusing his own modal harmonic idiom with the long abandoned practice of figured bass, achieving a highly idiosyncratic fusion of past and present. The output of the ensuing years testifies to Goehr’s desire to use this new idiom to explore ideas and genres that were already constant features of his work.

Goehr’s orchestral works include four symphonies, concertos for piano, violin, viola and cello, works for chamber, string and wind orchestra, as well as ensemble works. He wrote five operas, a number of ambitious vocal scores, and a rich body of chamber music. Goehr held a particularly close working relationship with Oliver Knussen, who recorded and gave premiere performances of many works including … a musical offering (J. S. B. 1985)… (1985), Idées Fixes (1997) and To These Dark Steps/The Fathers Are Watching (2011-12) for tenor, children’s choir and ensemble. Associations with other world-class orchestras, soloists and conductors produced numerous works: The cello concerto Romanza (1968) was written for Jacqueline du Pré and Daniel Barenboim, Bernard Haitink and the London Philharmonic Orchestra premiered Metamorphosis/Dance (1973-74), Boston Symphony Orchestra premiered Colossos or Panic (1991-92) under Seiji Ozawa, and Two Sarabandes (2014) was commissioned by Bamberg Symphony who premiered the work with Lahav Shani.

Through the chamber music medium, Goehr gained an unprecedented rhythmic and harmonic immediacy, while his music remained ever permeable by the music and imagery of other times and places. Marching to Carcassonne (2003) for Peter Serkin and London Sinfonietta, flirts with neoclassicism and Stravinsky. The set of solo piano pieces Symmetries Disorder Reach (2007), a barely disguised baroque suite, was premiered by Huw Watkins, and …between the lines… (2013), written for the Scharoun Ensemble Berlin, traces its lineage back to Schoenberg and Schubert and Shakespeare inspired Since Brass, nor Stone… written for percussionist Colin Currie and the Pavel Haas Quartet which won the chamber category of the 2009 British Composer Awards.

Goehr’s work and commitment to new music was recognised in his lifetime by numerous prestigious organisations. An honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a former Churchill Fellow, in 2019 Goehr was made an Honorary Member of the Royal Philharmonic Society in recognition of his lifelong contribution to musical culture. An archive of Goehr’s manuscripts is curated by the Berlin Akademie der Künste where it will be available to future students of composition and researchers.

The collaborative book Composing a Life by Goehr and composer-musicologist and former pupil Jack Van Zandt was published by Carcanet in October 2023. One of Goehr’s final work, Ondering (2023) for string quartet was premiered by the Villiers Quartet at the Royal Northern College of Music to mark the occasion.

The world premiere of Goehr’s Seven Laments for solo clarinet performed by Ib Hausmann will be part of Langenselbolder Klassik-Festival in October 2024 and Ensemble 10:10 conducted by Geoffrey Paterson will perform Sinfonia (1979) in Liverpool in March 2025.

Sandy (to all who knew him) passed away on 26 August 2024 at home in Cambridgeshire.

photo: Tom Hurley

Comments