Review: Berlin says eat your heart out

OperaOur roving critic Susan Hall has been to the German premiere of the George Benjamin opera, Written on Skin.

Here’s her report:

Written on Skin enjoyed its Berlin premiere at the Deutsche Oper. The George Benjamin/ Martin Crimp work is a hit. While no one leaves the opera house whistling the harmonic modulation, in fact they have been charmed by its rhythm, drama, colors and texture.

Not all contemporary composers have the audience’s engagement in mind. Mozart did. Benjamin’s first and most important mentor, Olivier Messaaen, called Benjamin ‘Mozart.’

Benjamin talks about looking at the big picture. The work has strong structural underpinnings. Cumulative tension builds, an unbroken arc from the first note to the last. Benjamin observes an arrow cutting through fifteen scenes. Fresh sounds surprise the ear and reflect the continuing drama. Tension is maintained and new inventions introduced.

The audience hear and feel effects without knowing exactly what they are. Yet the story of a love triangle is clear. Just not real or normal. The Protector (Mark Stone), owner and possessor of all he beholds, his illiterate and battered child/wife Agnes (Georgia Jarman) and The Boy (Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen), an illuminator hired by the Protector to create a book detailing the richness of his life.

For Benjamin, first the ear hears, then the mind interprets and finally the eye sees.

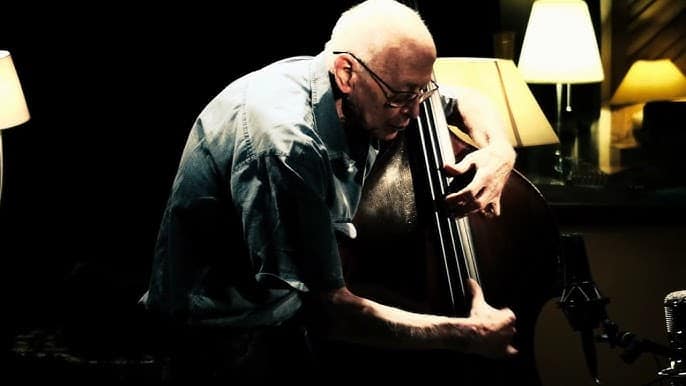

Felix Mildenberger conducts in Berlin. He brings out the opening ruckus, a dissonant melange of strings, brass and winds, letting them settle, as they often do in the work, into more conventional harmonics. The unusual contrabassoon grumbles along, threatening. A glass harmonica is decorative and adds to the rainbow of colors.

Until he wrote Written on Skin, Benjamin had never created a work longer than an hour. Expanded time gave him the chance to bring back notes and figures when the listener has forgotten them. His play with the top C engages.

The first top C is played softly by the orchestra. It is then the first note Agnes sings. Jarman has a glorious high C. At the end of Act II, she sings the top C again, in “Make him cry Blood.” The final word of the final Act is ‘mouth,’ sung on top C. We bid farewell to the top C in the epilogue. Listeners can take pleasure in the aha-C-recognitions.

For Benjamin the singing voice is paramount. The principal singers hold long, beautiful vowels. Jarman can warble like a Messiaen bird. The Boy gets Handelian decorations.The Protector is almost guttural in his masculinity. Yet Stone brings his softer side to this role and Agnes jumps off into the ugliness of pain when it grips her.

The librettist Martin Crimp creates both narrative and personal dialogue. Two seemingly separate points of view are blended. Sometimes they twist around each other like Agnes twisting in her sheets with new found erotic feelings.

The centrality of words is clear. Agnes insists The Boy reveal their affair to her husband. When The Boy resorts to words to tell their story, she wants to see their shapes: Love, mouth, hands.

The overarching movement of music and drama is forward. This thrust Benjamin considers a crucial part of engaging an audience.

Angels are a critical presence. Familiar figures in Berlin, they watch over the city. The angels on stage march quickly back and forth over a thousand years, keeping us in the eternal present of the millennium.

Katie Mitchell directs, as she did the original. Her frequent collaborator, Vicki Moritmer, provides the set. Most of the action takes place in the angels’ work room and in the central room of The Protector’s house, furnished alternately by a dining table and large bed. Lighting by Jon Clark moves us from room to room by beaming light and then cutting it.

Opera lovers are rushing to hear this grizzly tale of a jealous husband who cuts the heart out of his wife’s lover and makes her eat it. The hidden musical and dramatic art of composer and librettist holds us in its grip. Everyone wants to hear this work again.

photo: Ben Uhlig/DO

Spot on. It’s utterly phenomenal. I saw it first time round with Barbara Hannigan, Christophe Purves et al and was entranced from start to finish. A masterpiece the like of which I have seldom heard. Lucky old Berlin to be getting it now.

Benjamin writes in the tradition of Viennese expressionism, which was the last period of traditional opera writing, which indulged in misery-saturation and the suitable cauldron of dissonances, low life, psychic disintegration, etc. etc.

That stance has meanwhile become very traditional, because it seems to combine both ‘modernity’ and effective music theatre (of a kind), so composers can feel ‘oldfashioned’ and ‘modern’ in the same time. Viennese expressionism – Berg’s Wozzeck and Lulu, Schönberg’s Erwartung and Glückliche Hand – had one foot in the tonal tradition and the other firmly in psychic misery which required lots of dissonance and ‘shocking’ chords (‘Nein… nein…. NEIN….!!!’ + crashing fortissimo 12-tone chord; Lulu’s murder).

That operatic territory was prepared by Strauss’ Salome and Elektra, and enthusiastically picked-up by Schönberg and Berg, who both attended as many performances of these operas as possible.

When Strauss went on to write a much more traditional Rosenkavalier, this was considered – by ‘progressives’ – as a cowardly backstepping. But in fact, it was another form of progress, in terms of quality and a much wider range of expression than pure, undiluted misery would allow. When, and where, will composers of today get the point?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DE_XnB_mcwU&list=RDDE_XnB_mcwU&start_radio=1

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l5nwxwyNe-U

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zUA81xE-QLM

For people who long to recognize something of their own life experience in music, this seems to be an excellent work. We know that George Benjamin is brilliant in his colourful scoring. He is one of the most traditional composers of 20C modernism.

I dunno, but if I were writing the review, I’d probably stick this sentence much closer to the top — say, in the first paragraph, maybe?: “Opera lovers are rushing to hear this grizzly tale of a jealous husband who cuts the heart out of his wife’s lover and makes her eat it.” Oh, tell us more….

I love this stuff! Isn’t everybody fascinated by other people acting-out their own fantasies? Cutting-out heart stuff etc. is so much more exciting than typing letters, emails, SD comments and the like, yes suddenly you feel so much more alive & you don’t have to listen to the underpinning music.

Sally

“Grizzly”? Unbearable.

The conductor Felix Mildenberger was a find for me. He imparts both clarity and an excellent sense of scope to this opera. I will not be surprised to see him back at the wonderful Deutsche Oper.

The Germans love modernist opera, if possible combined with Regietheater, then they get it double. Of course nobody likes it, audiences go to these productions out of a collective feeling of guilt and obligation: they want to be modern, morally decent, and supportive of their beloved opera houses. Contemporary modernist opera symbolizes collective postwar historic guilt because the nazis condemned modernism, so embracing stylized utter morbidity gives them the feeling that they are ethically flawless – in spite of their own lives being completely devoid of the type of goings-on on the stage that they approvingly watch from their comfortable seats. The most sophisticated, decent, morally-upright German bourgeois couple comes home from devastating depravity with an approving smile of having fulfilled their cultural obligations and knowing that they themselves never ever will descend into that pit of dehumanized misery.

In one of the questionaires organised by the well-known music website (redacted), the reaction most received at the question whether the listener enjoyed the production of (redacted), was: ‘Oh, it was awul, truly awful, but I enjoyed it immensily!’