NY Times puffs up a defence of its chief classical music critic

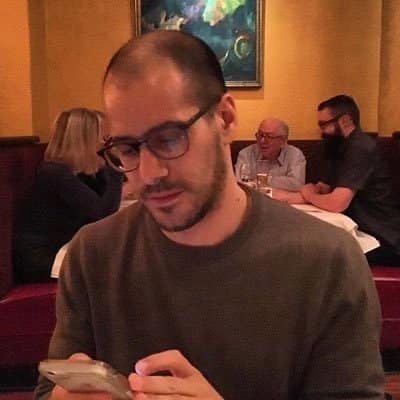

NewsDays after Zachary Woolfe devoted the closing paragraphs of his Boston Symphony review to a hostile briefing against its music director Andris Nelsons, the New York Times has devoted a full feature to his working methods.

Under the sub-head ‘Zachary Woolfe, the classical music critic for The New York Times, shared how he endeavors to make his writing accessible to both neophytes and experts’, we read such vital insights as:

– “I think what people are interested in is passion,” Mr. Woolfe said. “Even if you didn’t understand every word, my goal is for you to be drawn into my pieces because you can tell that I really care about what I’m writing about.”

– It’s a constant work in progress: how to make everyone feel like an article was written with them in mind. You want experts to be able to glean something, and for the neophytes to feel challenged, but not left in the dark or talked down to. And that comes down to choices about how to describe things and how much insider language to use, like “diminuendo” or “staccato.”

– It makes me super happy when there’s disagreement about my reviews. I do not aspire to them being universally agreed with. I enjoy the conversation. But hopefully there’s a sense that I’m operating in good faith and with fairness, even if you disagree with the conclusion.

Humility is so underrated these days.

Comments