A London memorial at last for Beethoven’s British violinist

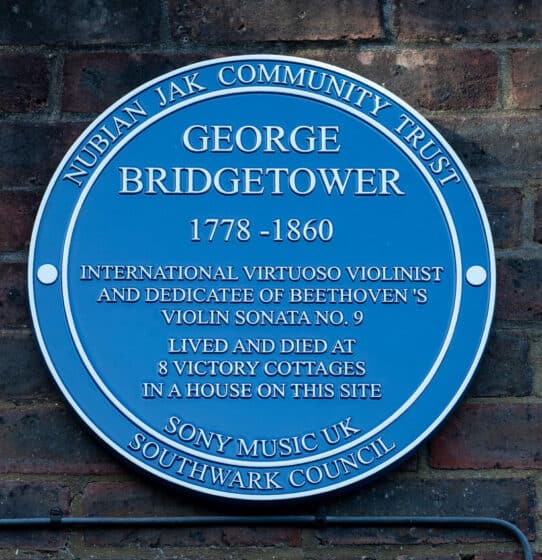

NewsThe unfortunate George Augustus Polgreen Bridgetower – a British violinist who gave the first performance of the unnamed Kreutzer Sonatas together with its composer – was recognised today with a blue plaque in the street where he lived, in Pechkham, southeast London.

BLM campaigners have sought to make Bridgetower a poster boy for the oppression of black musicians in classical music. An example of prevalent ignorance was given at the plaque unveiling:

Kwaku, a music historian who specialises in black British music, said: ‘George rose to be the most famous British composer of the early nineteenth century. He was a phenomenal musical talent – history says he didn’t need rehearsal which is why Beethoven was so impressed by him. It’s great that Southwark Council, Nubian Jak and Sony Music have put up this plaque. And to know that he lived in Southwark – that’s fantastic.’

I shall deal with the racial complexities of the Bridgetower case in my forthcoming book, Why Beethoven.

He was a British violinist, that’s all you need to know. As many have pointed out, Britain is a damned good place to be black. Let’s stop listening to this irrelevant, ignorantly provocative and typically divisive American-influenced cr*p and get on with enjoying who we are.

For readers interested in footnote fodder, Bridgetower’s father (“Friedrich de Auguste,” as he is listed in his employment document) was a “chamber page” in service to Prince Nikolaus Esterházy (yes, Haydn’s Esterházy) in 1779 at an annual salary of 200 florins with an additional amount for board for him and his wife. On May 16, 1803, Joseph Carl Rosenbaum (an erstwhile Esterházy employee) wrote in his diary that at the Theater an der Wien he again met Bridgetower, “first violinist of the Prince of Wales, and invited him to dinner tomorrow.” On the 24th, he attended the concert at the Augarten at which Bridgetower and Beethoven played the Violin Sonata no. 9, op. 47. “It was not very crowded, and a select company.” The autograph of its first movement bears the dedication “Sonata mulattica Composta per il Mulatto Brischdauer gran pazzo e compositore mulattico.”

As a footnote to your footnote: another of Beethoven’s autograph “dedications” was of the violin concerto to Franz Clement, “Concerto par Clemenza pour Clement, primo Violino e Direttore al Theatro a Vienna, dal L. v. Bthn. 1806”. The concerto was then actually dedicated to Stephan von Breuning, just as the violin sonata was actually dedicated to Rudolf Kreutzer. I would guess that there is a difference between “written for performance by” (per/pour) and “dedicated to”. Also interesting: Clement like Bridgetower was a violinist, had been a child prodigy, was taken on tour including London by his father, who was (like Bridgetower’s) a servant to a Viennese nobleman. Bridgetower (aged 12) and Clement (aged 10) gave a concert together in 1790 at the Hanover Square Rooms, London, under the patronage of the Prince of Wales. Another coincidence: both had to sight-read parts of the score at their respective first performances. (Good info on Bridgetower here: https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/features/blackeuro/pdf/bridgetower.pdf)

Errata: Clement did not have to sightread the solo part, but Beethoven didn’t complete the score until the last minute so the orchestra will have had to do some sight-reading; and Austro-Hungarian rather than Viennese.

Some sources do suggest that Clement DID sight read at least portions of the Concerto’s solo part, which maybe explains Beethoven’s little joke about “clemency” from Clement. Clement has come in for his share of disdain for playing a piece of his own between the first and second movements, but when one reads that some of Beethoven’s piano concertos were premiered with an entirely lengthy multi-symphony program between the first and second movements, the case can be made that Clement’s brief showpiece with the violin held upside down meant presenting the Violin Concerto as more of an artistic whole than perhaps was the norm. And it also helps explain why concerto first movements of that era seem to beg for the applause that is now all but forbidden.

As for George Bridgetower, everything I have read suggests that he was an astonishing talent who for some reason ended his career early. He lived long enough to know, and some sources say, make music with, Camille Saint-Saëns, who in turn lived long enough to know, and make music with, violinist Albert Spalding, who in turn lived long enough to record the Beethoven Violin Concerto in the LP era. Maybe that does not quite equal the famous hypothetical of a musician who studied with Haydn and taught Schoenberg but it does illustrate how compact much of what we regard as the history of music can be made to look.

And I did not see any prevailing ignorance in the excerpt of the remarks of Kwaku at the plaque ceremony. I suspect many would take issue with the opinion that Bridgetower rose to become the most famous British composer of the early 19th century. I don’t know what he wrote that was so widely heard, and whether the British can really claim him is also a matter for discussion, but maybe for some period of time he was the most famous composer. At the very least it ranks with the sort of gracious exaggeration one hears at a memorial service – or plaque unveiling.

… the most famous British composer of the early nineteenth century? No.

Dedicatee of Beethoven’s Op. 47 sonata? Not really. First performer of it, yes.

Interesting for historians of music? Yes, of course.

Dear NL, what was the “example of prevalent ignorance”?

For a newspaper report, it is not too inaccurate (though Beethoven did not have a niece, and Bridgetower didn’t travel the world, only parts of Europe). Whether he became a friend of Beethoven in any real sense is dubious (he was only in Vienna for a few months), and it is unlikely that Beethoven intended a formal dedication of the sonata to him. I wonder if Bridgetower really appreciated being called “a great madman and mulatto composer”? There is only one source for the story about the quarrel; in 1858 (over fifty years after the event) a violinist called Thirlwall says that Bridgetower had told him that “they [Beethoven and Bridgetower] had some silly quarrel about a girl, and in consequence Beethoven scratched out the name of Bridgetower and inserted that of Kreutzer — a man whom he had never seen”. In fact, Beethoven had met Kreutzer earlier, and he did not scratch Bridgetower’s name out of the manuscript. Time may have played tricks with memory.

But apart from nit-picking, it is good that George Bridgetower is commemorated with a blue plaque; he had been celebrated as a child prodigy, and continued as an active and well-respected musician in London at least until the 1820s.

I am glad to see Bridgetower recognized, and even though he was not the final dedicatee of the violin sonata, he definitely should have been. I so wish we could change its nickname from “Kreutzer” to “Bridgetower” as Kreutzer never performed it, and until Bridgetower and Beethoven quarreled, it was supposed be dedicated to him. Beethoven was extremely impressed with his virtuosity.

As the guy is a ‘specialist’, I would hate to hear a non-specialist at work! Pity the council can’t ever get the facts right for the plaque. A simple reference to a Beethoven biographer would do.