Philistines take charge at Covent Garden: first night review

NewsAlastair Macaulay reviews Saint-Saens Samson et Dalila at the Royal Opera House, special to Slipped Disc

For those of us who came to opera when productions were visually glamorous and the stories were usually ones we knew in advance, the director Richard Jones has long been a salutary breath of change: clever, nutty, capable of both alienating and entertaining an audience at the same time, never content with surface values. Since at least the 1990s, he’s been shaking up the British opera world by making even its best-known stories rivetingly unfamiliar, and by refusing to make this genre comfortably pretty to look at.

Perhaps no Jones production ever seems definitively right – each is too disconcerting for that – but several of them move brain and heart at the same time. In his new production of Saint-Saëns’s 1877 opera Samson et Dalila for the Royal Opera at Covent Garden, neither Samson nor Delilah are quite the characters we thought we knew. As for the Philistines – for whom Dalila betrays Samson – they change character to startling effect.

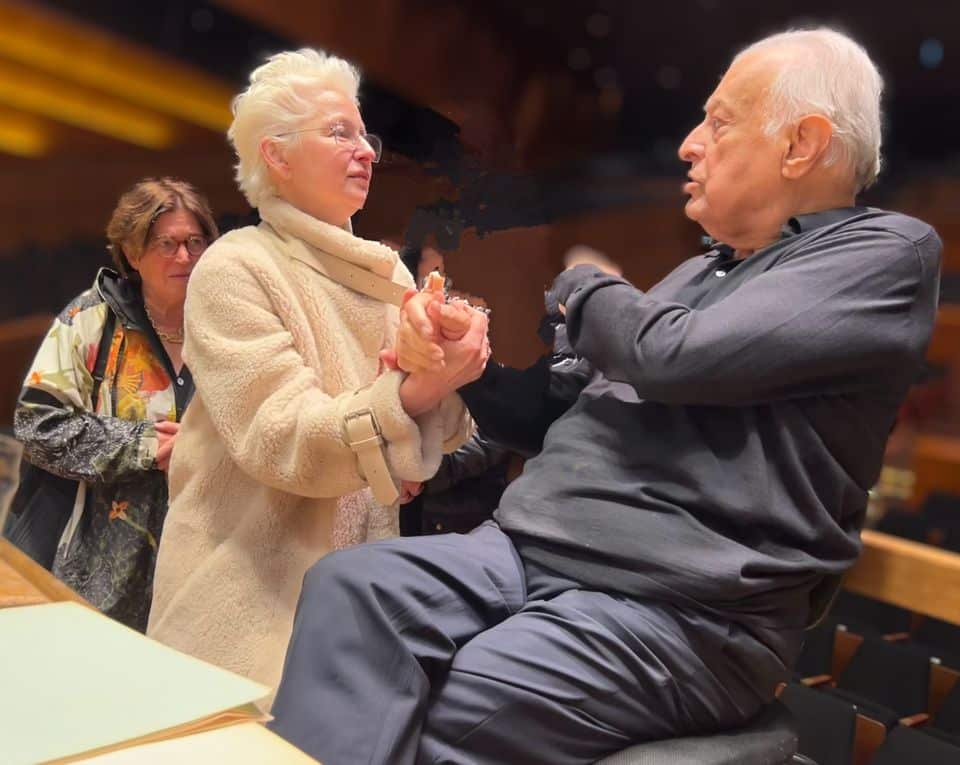

Likewise the conductor and Royal Opera music director Antonio Pappano, while eliciting orchestral playing of great beauty, produces multiple revelations from the score. Just the recurrent bass notes in the opening orchestral sequence are startling – like depth charges from within the bowels of the opera house. Samson et Dalila is a work of considerable musical sophistication, with an opening chorus that deliberately, and like no other nineteenth-century opera of note, evokes Handelian music drama – but in Pappano’s rendition we also hear echoes of Wagner, Bizet, Tchaikovsky. In Act Two, descending and ascending orchestral scales course like opposite principles: flesh versus the conscience.

The opera’s Israelites and Philistines are updated from any Old Testament era to a modern-dress tension, not unlike today’s Israel versus Palestine. Military zones overlap with religious worship (but with Israelites routinely oppressed by the occupying enemy). Jones and his set designer, Hyemi Shin, divide our view with scene changes. We’re often watching contrasting half-views of a complex picture; we never grasp the whole scenario.

The mezzo soprano Elīna Garanča, a woman of exceptional facial and physical beauty, was a subdued, unarresting Dalila for New York’s Metropolitan Opera, in 2018. Here, however, she presents the most multifaceted Dalila of my experience. (I go back to the great Shirley Verrett in 1980.) At first, Garanča plays a femme fatale as if she herself didn’t quite believe it – though the humour with which she does a seductive little dance for Samson is endearing. Her sexy undulations of the pelvis are gorgeous but not overdone, her little sideways skips are impish. (The choreography is by Lucy Burge.)

But when she’s alone and opens up about wreaking vengeance on Samson for her gods, Garanča-Dalila shows the biting sincerity of a true zealot, both icy and ardent. Though the role lies low for her voice, she shows ever greater incisiveness in chest tones as the opera moves on, while the lustrousness of her upper notes and the luminous cascades of the few coloratura passages all shine bright.

In the final act, when Samson is blinded and captive, we find that the Philistines’ god Dagon’s temple turns into a vulgar hall of conspicuous spending and gambling. That’s one shock. Another is that Dalila is visibly embarrassed by this gross side of the Philistines, even though they treat her as their sexy, pin-up heroine. Silently, she distances herself from their antics; she’s embarrassed by her colleagues’ tacky degradation of their own religion.

The Korean tenor Seokjong Baek – who was announced in March as the replacement for Nicky Spence when leg injuries prevented Spence from rehearsing this production – is the most youthfully vulnerable of Samsons. He doesn’t try for the clarion heroics of other Samsons. (The Titanic power of Jon Vickers remains indelible even after four decades.) Baek’s voice carries clearly throughout its range, but he sings and plays Samson as an unworldly innocent who has been propelled into the heart of action, often singing high notes quietly: the strong man is showing his tender, event sweet, side

And this youngster’s need of Garanča’s Dalila seems Oedipal. His hair flows smoothly down his back to his waist; Dalila plays with it, sensuously, long before she knows it is the secret of his strength. (At company bows, Baek and Garanča returned to the stage from opposite sides, but the happy, unshowy generosity with which Garanča, a far more established star, made sure that the newcomer Baek won the audience’s recognition was very touching.)

None of the singers are or sound French, but the Polish baritone Lukasz Goliński (the High Priest), the Georgian bass Goderdzi Janelidze (as “Samson’s rabbi” – a role originally called “an old Hebrew”), and the Congo-born bass Blaise Malaba (Abimélech) all point French words eloquently at times. They’re all good performers; none of them deliver great singing. And as for French diction, I noted that I consulted the surtitles least when Baek was singing.

Imperfections abound here. The tie-dye patterning of the wallpaper in Dalila’s home is naff to the nth degree: you can’t believe that a woman who (thanks to Nicky Gillibrand’s costuming) dresses with this kind of colour would keep home somewhere that dated and bland. Yet so what? This Samson et Dalila, new and unsettling, is a major event in music theatre.

Comments