Memoir 2: I played the great master’s last concert

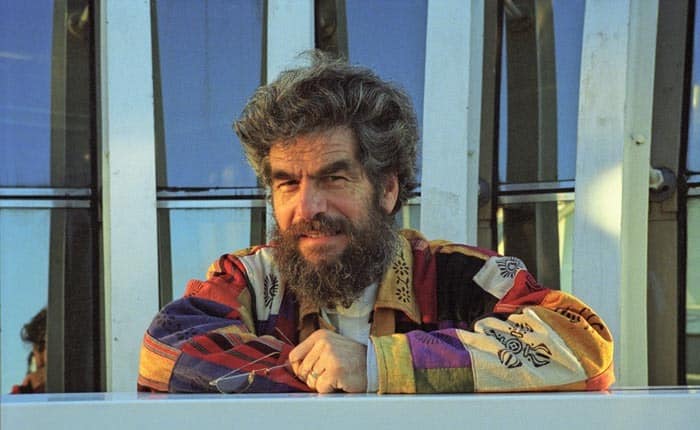

OrchestrasThe brass player Peter Bassano, in his new memoir Before the Music Stopped, remembers taking part in Sir John Barbirolli’s last rehearsals before his sudden, unexpected death in July 1970:

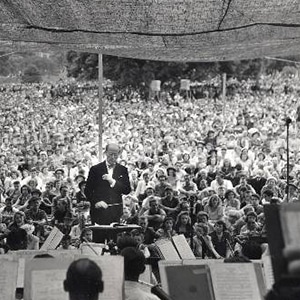

Other musical organisations that attended (Expo70 in Japan) were Deutsche Oper, Orchestre de Paris, Berlin Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, Leningrad Philharmonic, Bolshoi Opera, New York Philharmonic and the English Chamber Orchestra, in such company, this was a very high profile engagement for the New Philharmonia. There were to be several performances of Mahler 1st Symphony conducted by Barbirolli.

My role was a very subservient one. In the score Mahler calls for additional brass players just at the very end of the last movement. Not knowing how Barbirolli was going to work I was booked for all of the rehearsals. As it happened he played through each movement in its entirety before starting detailed rehearsal. It struck me that this was a sensible approach to rehearsing rather than some conductor’s approach of nit-picking from the outset.

When we arrived at the second movement I thought his initial tempo slower than other recordings I knew. However after I later listened to Austrian country dances, Barbirolli’s choice of Ländler tempo is the one that I have come to think Mahler had in mind. This approach gives the opportunity to really maximise the excitement when the accelerando comes at the end of the movement.

When Barbirolli got around to detailed rehearsing he was very particular about the string playing, the sound quality, bowing and especially demanding the realisation of the portamenti indicated by the composer but which orchestral players – having perfected their position changing – are often reluctant to observe. The heart-rending melodies and radical changes of mood in the last movement were formidably controlled.

Before we left for Japan there were performances of the Mahler at the Royal Festival Hall and the Fairfield Hall in Croydon which doesn’t possess the largest of stages. In the afternoon rehearsal we arrived at the coda of the last movement when Mahler instructs the horns to stand. Because of the positioning of the brass section as a whole principal trumpet, David Mason’s view of the conductor was impaired and he started to make a fuss.

Sir John spotted this and ploughed his way through the viola section, when he reached the trumpets he lit a cigarette. “Hello David” he said in his gruff London accent “what’s the matter?” To which David answered “when the horns stand up I can’t see you”. Sir John replied “you remember when I used to play the ‘cello”, “of course, I do but what’s that got do do with it?”, “well I was deputising in the Lyceum Ballroom, one matinee, when there was a number in the pad with chord symbols. So I said to the conductor “what do I do here?” To which he replied “bugger about in Bb”. When those horns stand up and you can’t see me, bugger about in D major and we’ll be alright!” The performance was both exhilarating and wonderfully emotionally touching.

There were two soloists for the tour, pianist, John Ogden joint winner with Ashkenazy of the 1962 International Tchaikovsky Competition playing Beethoven 3rd Concerto and Ravel Concerto in G major. The other soloist was the singer Janet Baker whose recordings of Mahler Rückert Lieder and Kindertotenlieder with Barbirolli had won critical acclaim. Further rehearsals in the last week of July took place without any involvement from me. The repertoire was the Rückert Lieder, Sibelius 2nd Symphony, Britten Sinfonia da Requiem and Beethoven Eroica.

There was a short pre-tour press conference on 28 July which Sir John attended and after which he went home. In the early hours of the following morning he died. The musical world went into mourning, not least in Japan, where Barbirolli’s first visit was eagerly anticipated.

The orchestral musician knows when there is a ‘great’ conductor standing in front of them. Those gifted musicians possess a charisma which is only inherited by a small number. The Mahler performances with Prichard and Ted Downes were good, but both conductors lacked that special indefinable quality – the ‘greatness’ – that Barbirolli brought to his music making.

How fortunate I am to have caught the last two concerts of this superb conductor and wonderful human being.

Similar tempo for this movement to Bernstein’s, despite Mahler’s much quicker metronome mark, as observed scrupulously by Abbado in his later performances. BTW didn’t Peter Bassano’s name used to be Peter Goodwin?

My name was changed in 1990, the reason is explained in the book.

Based on this excerpt, I look forward avidly to reading your memoir. This character sketch of Barbirolli is priceless!

It is always good to be reminded of the wonderful musician, and terrific all-round Mensch, who was John Barbirolli. His death in the early hours of 29th July 1970 was indeed ‘sudden’. But was it ‘unexpected’? The man himself, and those close to him, were aware that his health had been hanging by a thread. Hence the valedictory, even numinous, feel of the Elgar First which he had given (with the Halle) at the Kings Lynn Festival that month. The recording of that concert seems to have disappeared from the catalogue. The BBC would do well to re-release it.