Where the Berg concerto violin lives now

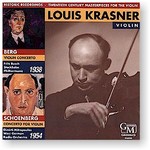

NewsThe American violinist Louis Krasner is famed for commissioning and giving the first performances of outstanding concertos by Arnold Schoenberg and Alban Berg.

Krasner, who died in 1995 at the age of 91, played a Gagliano violin.

In the last phase of his performing career, he served as concertmaster of the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra from 1944 to 1949.

The death has just been reported of Harry Nordstrom, 98, a music professor at Carleton College.

After wartime Army service, Harry played a couple of seasons in the Minneapolis Symphony under music directors Dimitri Mitropoulos and Antal Dorati.

His obituary recounts that his grandson, a hip-hop artist Rolf Haas, now plays the Gagliano violin that Harry acquired from Krasner.

Sic transit harmoniae mundi.

Comments