Fugue off with Glenn Gould

Daily Comfort ZoneA television adventure in articulacy from March 1963.

Warning: tenors may take offence.

A television adventure in articulacy from March 1963.

Warning: tenors may take offence.

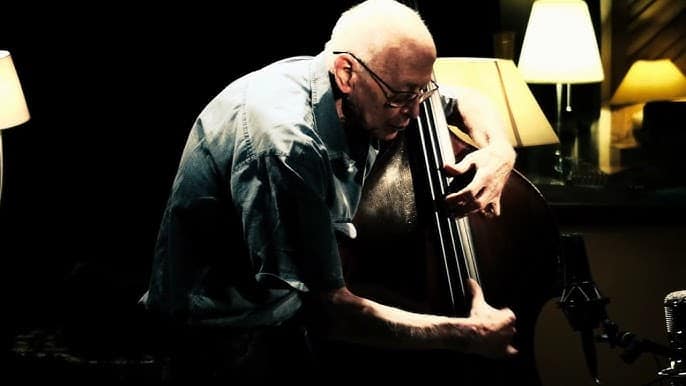

The US jazz bassist Barre Phillips, resident in…

The death has been made known of the…

Colorado will never sound the same without Margaret…

We’re hearing that the Vienna State Opera has…

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

The first violin looks like Albert Pratz, probably the top Canadian violinist of his time. Former NBC Symphony member. Later Toronto Symphony concertmaster.

Albert Pratz (13 May 1914 – 28 March 1995) was a Canadian violinist, conductor, composer, and music educator. He was awarded the Canadian Centennial Medal in 1967. He was concertmaster for the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra from 1966–1969 and the Toronto Symphony Orchestra from 1970-1979. He joined the Festival Trio chamber group in 1953 whose other members included the cellist Isaac Mamott and the pianist Glenn Gould. In 1961 he joined the faculty of the University of Toronto where he founded the Canadian String Quartet (active1961-1963) heard here in Mozart’s K.396.

Mr. Pratz was also heard in some of the earliest recordings Glenn Gould made (when he was about 20 years old).

On a 1951 Hallmark Records disc (reissued in 1982 on Vox/Turnabout), he played violin arrangements of brief pieces by Shostakovich, Taneyev and Prokofiev, with Gould at the piano.

Pratz said the Russian pieces were recorded “about 1:30 in the morning”– which was apparently fine with the pianist.

Correction: the Köchel number for Adagio and Fugue in C minor is 546 (not 396). The C-minor Fugue was first composed in December of 1783 for two pianos (K. 426) then re-arranged for strings, with an introductory Adagio, in June 1788 – the prolific summer during which he also penned his last three symphonies.

Gorgeous! Thank you so much

for posting.

According to GG, Mozart lost his identity when writing fugues. This would mean that M’s identity is a fixed thing and glued to the operas, symphonies, concertos etc.

But the Adagio is very clearly Mozart, with all the surprising chromaticisms, and the Fugue sounds like a Beethoven fugue in his late string quartets. Do we then say that Beethoven lost his identity when writing fugues?

It’s again a bit of the quasi-musicological nonsense with which Gould liked to pose, to show an intellectual veneer, which he did not need.

The Mozart piece is a master piece and entirely Mozart, being another side of his imagination than the ‘classical’ one. Mozarts incorporation of baroque contrapuntal writing in his own, very different style, is one of the first examples of ‘going forward’ by ‘going backward’, one could say: a ‘neoçlassical impulse’, just like Beethoven in his late string quartets and piano sonatas took-up his memories of his early studies of Bach and Handel, and created something strikingly new and superb. These pieces (like the Mozart ones) are often described as ‘standing outside the Zeitgeist’, because following the composer’s utterly personal whims.

The whole notion, in the territory of the arts, of ‘progress’ and ‘Zeitgeist’ rests on easily repeated prejudice and very restricted knowledge of history.

This is a better performance:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_VTtu9fGkWo