A young conductor tells veteran player what’s wrong with orchestras

Comment Of The DayReader’s Comment of the Day (to original post here):

Dear FrauGeigerin,

Of all your comments on this website I ever saw, this one is the first one that isn’t purely insulting, and I agree for the most parts with you. Since you are an orchestral player (and from what you tell us, it might be with a certain Radio Symphony?), I can understand your frustration but would also like to point out your opportunity. The truth is, most of these 24 young conductors (I met almost all of them) aren’t selfie-taking, self-image-obsessed at all. Some are sweaty, as is Noseda. Some are jumping, as are many that aren’t too old. Same for energy-driven.

The real problem is the ignorance, and since I went through the typical conductor’s education I can see how this manifests itself. Every conservatory or university tries to teach to a young person something about conducting within 3-5 years, depending on which degree a school can offer. Most students are beginning to conduct there, because only in very few countries there are possibilities to study conducting before college level. Everybody has a different background, some are pianists, some are orchestral players, some are composers. Now 3 or 5 years is incredibly little before going into professional life. I would assume you played the violin longer than that before you won your audition.

After these conductors finish school, they are stressed because they aren’t yet ready and have to take any opportunity to keep learning. Assisting someone, doing a family concert here and there. If they don’t get management, they are out of the game soon. And if they get far in a competition, they might get some gig somewhere, or a manager. It’s just a small hope to be allowed to develop further.

Now the problem when we are taking the first steps in the professional world is – hardly any orchestra player will walk up to us and give us honest and constructive feedback. Only the ones that like us will talk to us, all the rest just disappears, maybe doesn’t even greet us in the hallway.

A lot of us aren’t quite sure if the things we say or do are done the best way possible. As long as it sounds better we have to be ok with what we did, knowing that it might be totally unrelated to the words or gestures we used. Sometimes the orchestra just gets better by playing it twice, or the concertmaster takes over.

So my personal wish to you is: When you have an unexperienced conductor in front of you, take the opportunity to tell them in the break if something is technically impossible or unclear. And more importantly, tell them which words to use instead! If they stay in the game, orchestras all over the world will suffer for decades from those problems, but you personally can help solve them! Maybe someone won’t be able to change immediately, but if you use good words, they stay with us and we think about them for a long time. If I ever have the chance to conduct your orchestra, I am waiting for your feedback and I’ll be honored when I get it!

And if I guessed your orchestra right, why don’t we go for coffee some time… 😉

Best wishes!

I’m guessing that she is in the DSO Berlin, who have had some really bad ones who would not benefit from “good words”.

I’m guessing it doesn’t matter what orchestra she’s in, she would be like this no matter what.

Maybe. I don’t think the name of the orchestra is relevant. The real problem is that inexperienced conductors who should be earning their stripes with youth orchestras, asissting in operas, working as Kapellmeister in a small city etc. are promoted to “stars” soon after finishing their training (if any at all!) and to conducting professional orchestras, not because they are ready for it (or have merit), but because they are a good “product”, because they are what the audiences came to see (not to listen).

Frau, if this is happening in your orchestra you need a new general manager.

It’s the manager’s job to decide who should be conducting their orchestra.

Agents are paid to place their clients. Conductors go where their agents find work. You are basically asking them to vet themselves which is absurd.

If you have a problem with the quality of young conductors you have to work under in your orchestra you need to make that clear to your manager or orchestra committee.

Agreed, but it’s by all means not their fault to land in a good chance, it’s the agency’s interest to push “fresh” talent to the front. Naturally this is over simplistic cause the youngsters accept whatever they’re offered and that’s the problem. Also, we have way too many schools teaching “conducting” who actually don’t do their work properly. Lastly, bad recruitment in the schools is also a big issue.

Excellent letter of the day. Just like the majority of Senators in the US Senate think that they’d be a much better President than whoever is in THAT job, orchestral players all seem to have the proverbial baton in their instrument cases. All conductors can learn from players at any time in their careers, but I suspect that only the more established conductors get that “respect”. In rehearsals I’ve witnessed Bernstein take a suggestion from the trombones and Arvid Jansons take a suggestion on a cue from the basses in the Halle. This happens all the time. While most orchestra players when asked who their favorite conductor is react as if I’d asked a mouse who their favorite cat might be, in reality, most great orchestral instrumentalists love a really great conductor and may take some hints and tips with them should they ever do any conducting on their own. The snipers will snipe, who cares?

I was at 5 great concerts with LB several more with Jansons: he remains the conductor whose concerts were the most emorable even after 47 years

I understand what this fellow conductor is expressing – it doesn’t help any of us when orchestral players are hostile to young conductors when a more constructive approach would be to obviously just give advice and feedback. However, I do also think FrauGeigerin is exacting her anger on the wrong people – the issue and her frustration is really with the industry and what it has become, which is the same for many of us.

The way the industry currently works for young conductors is very problematic and worrying. Only a couple of decades ago, that is to say, before the internet, social media and conducting competitions became commonplace, young conductors, including of course those who are now world class names, were able to build up their experience and career quietly and professionally without the pressure of too much public exposure and too much ‘info spread’.

Now, with the ridiculously fast pace of spread of information and need to remain ‘relevant’ online, plus the professor mafia carousel that is primarily all competitions rely on, conductors are obliged not only to ‘make it’ as you said the moment they step out conservatoire, but to ‘make it’ fast, competitively and loudly. Needless to say even slipped disc is an unfortunate contributor to the swift news, catchy headline and comment culture.

Also worth saying that despite this, it’s not for us to expect the orchestra, especially a professional orchestra of a very high calibre to be forgiving of us – sympathetic maybe, but it’s not for them to be surrogate professors while we reap a moment of fame and glory before we are ready. Of course everyone is always learning on the job, even those at 50, but if we are being forced into the limelight to early and too soon, in order to as you say, ‘stay in the game’ – that unfortunately is no-one else’s fault but the industry, the trend-market, and the speed at which we are forced to become fully fledged conductors. Obviously, there will be backlash from orchestral musicians. There is nevertheless still the possibility to work patiently, while learning and building up experience without putting oneself forward too much – the catch-22 for us, is that choosing to do so you run the risk of being left behind in the race. But so long as we feed into the way the industry works because we ‘want’ a career and don’t challenge it ourselves, it will remain that way and cause the stress to both us and orchestral musicians.

The conductor himself alludes to the issue: command of a group of experienced (possibly insular) to perform in a manner that is different from how they’ve performed in the past. In some cases, the young conductor may not have spent enough time with this particular piece to have a fully-formed conception…and pros can smell amateur like blood in the water to a shark.

Experience is key, but I can’t imagine the challenge of conducting a world-class ensemble.

It’s often the precise wording a conductor uses which gets the players in exactly the right mood:

https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/latest/toscanini-rehearsal-rant/

He sounded frighteningly like a certain murderous German demagogue from the Third Reich.

When I first listened to audio of one of his rantissimos on utube, it was amusing reading people’s horrified reactions to being shouted at like this at work. I started thinking, well, if this orchestra produced great performances,and they certainly did under Artie T, they wouldn’t mind his riotous temper cos they knew he was a perfectionist & he justed wanted them to nail his vision of the work after all, musos wanna be able to make fantastic music as part of their work. After listening to this one, that idea’s already worn incredibly thin. I don’t think I wanna turn up to work every day to be bellowed at, endlessly.Who needs that?! In fact….delicately put…fk that for a game of soldiers.

A good and well written statement, which brings us to the important question: who does “make” a conductor? Not necessarily a teacher (but good teachers are nevertheless needed), not necessarily agents (but a good agent can have good advices for young conductors, and bad agents can ruin a personality and a career), especially not at all media and journalists (at the contrary, we see several young men and young women “hyped” by journalists without any consistency with their – very limited – skills, just because they are young, fresh and energetic: this is not the real point in conducting). Who then? Orchestra musicians. When I was young and without experience I actually craved for advice from orchestra musicians: nobody gave me any, except an older cellist at Munich Phil, who in a rehearsal’s break came to me and told me “Sie sind gut, aber geben Sie uns Zeit” (you are ok, but give us time). I was immensely grateful to him, and I really understood what he meant only later, but I would have preferred opinion and advice from those who didn’t like me. I could have avoided many mistakes knowing what I lacked at that time. Orchestras make conductors, this is the truth and it is right so. Therefore, dear orchestra musicians, give young conductors advice, do it nicely but do it, help them develop. It is in your own interest to help them to become good conductors. Please tell them to be humble, tell them to perfection their technical skills, tell them to breath with the orchestra, tell them to learn to show what they want and not to talk too much, tell them that orchestras love conductors who make the orchestra play well. The younger they are, the more they need it.

This is so important, and humble advice from a master. Like many pianists, conductors are thrown into situations that may be over their heads, and they cannot sustain a career that has jumped past several necessary hurdles. The wise ones will heed advice, when offered, and use the advice to evolve. Careers are not built in a day, and must stand the test of time. Today’s apprentices are tomorrow’s leaders.

Sorry for pressing thumbs down, was not my intention! As I wanted to undo it and therefore again pressed the thumb down button, it unfortunately didn’t undo it but the opposite happened – a second thumb down appeared… I tried again – a third thumb down and so on..! I thought, it is only possible to vote once so I apologize for the 6 thumbs down, I could not undo any of them..

One of my conducting teachers used to say you become a better conductor by conducting better orchestras. I personally have benefitted immensely from good constructive comments from orchestral players. Being open and establishing this dialogue when young is critical. Many orchestras complete conductor evaluation forms for their administration at the end of a concert, which are not conveyed to the conductor. I wonder whether a system could be developed whereby appropriate and important comments can be communicated in a supportive manner to the conductor, especially in one’s early years. These could be invaluable and perhaps orchestral players knowing their comments can be passed on will appreciate such an opportunity.

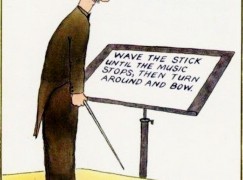

The only words experienced orchestral musicians need to hear from a conductor are “”Good Morning, ladies and gentlemen. The Brahms.”

They already know what’s about to transpire after observing the conductor walk across the stage and ascend the podium.

That’s clever, although not actually apropos to the topic. The question is what conductors need to hear from musicians.

Music universities should stop selling illusions. If you study 5 years at a music university – and in many countries this means: pay their horrendous fees – and do not do anything wrong, then they will usually give you a diploma stating that you are now a fully trained conductor. Of course that is a lie! Nobody would accept somebody fresh out of college as their medical doctor. In most countries, years of practical training are required before you are allowed to practice as an independent doctor, and no matter how smart you (think that you) are, you cannot shorten this time. Of course there is a lot of abuse in that system as well, but at least the young people who want to become a doctor are told honestly at the beginning that their education does not take 5 years but rather 15. If you want to be a baker or a plumber in most central european countries, then you have to assist an experienced baker or plumber for three years, no exception for anyone – but not even this is required for conductors. At least in the German system – which is somewhat special because of its heavy focus on the operatic repertoire, but still – there used to be the expectation that before you conduct your first performance, you spend a decade as a repetiteur at an opera house preparing the singers for someone else and maybe are allowed to assist that person if you are exceptionally talented. What happened to that Kapellmeister system? I think most singers would agree that you can tell whether the conductor skipped this decade in his education.

Even in the long distant past, people didn’t need to spend 10 years as a repetiteur before conducting your first concert. Most of those who later became famous were conducting provincial concert programmes by their mid-twenties. And frankly, conducting minor orchestras, and learning from the many mistakes that are made, is the only real way to learn how to conduct.

What an excellent letter. Orchestra musicians somehow think that great conductors emerge from the womb with their talents already formed. They refuse to understand that becoming great at anything takes practice and experience – And how else do young conductors gain those things without standing in front of an orchestra? “Well, not in front of MY orchestra because we are above that – we are the best of the best.” So you think that conductors learn and grow only from conducting student groups and community orchestras? They also need to drive the Rolls Royce – How else can they know that experience? I have personally seen any number of young conductors destroyed personally and professionally by nasty and mean orchestra musicians who don’t have the eye/ear to spot potential, and are too selfish to be helpful and encouraging. And god forbid they should actually mentor someone. Oh, right – that’s not in your master agreement. You don’t get paid for that time, do you? That’s not your job, is it? Then sit in your chair, unhappy and unfulfilled, and continue being part of the perpetual problem.

I am afraid you are cold in your guess (not important anyway). But I can give you some advice since you are a young conductor and you asked:

1- please, educate yourself. Not only in music, but also in literature, arts and philosophy. We had a not-so-young conductor (now with a first class international career) in my first f/t position in a professional orchestra about 20 years conducting Strauss’ Dance that mentioned in the middle of the rehearsal that the libretto of Salome was written by Hofmannsthal. I couldn’t take seriously that man anymore [please see point 3].

2- don’t waste the orchestra’s time with your needs. And if you stop please tell us why. If you make a mistake just say “sorry, I think I can do this better”. And that’s it: we are all humans and make mistakes.

3- please, don’t talk too much. If you have good conducting technique that’s all you need. We can understand you better if you show what you want. And this brings us to…

4- know what you want. And plan your rehearsals (then it is very likely that the plan will change, but at least you have an idea of what you want to achieve).

5- please, finish in time the reahearsal. Some of us might be hungry, need to visit the restroom or pick up our children from school. In my orchestra we are very tolerant, but in some public orchestras musicians might just stand up and leave when the time is up. You have been warned 😉

6- please don’t try to be original just for the sake of being different and unique. It is very likely we have played the standard repertoire many more times than you have conducted it. Please, build on that.

7- remember: we are there to make music. We (the orchestra) want to sound better and you can help us. That is your mission. Please, be the music, and be there for the music. Conducting should not be a way to make you feel “good” or important.

8- please, go step by step in your career. Don’t try to go from riding a bicycle with training wheels to piloting an airplane in 5 years. Earn your stripes in youth/community orchestras, assisting in opera, working as accompanist in opera…. give yourself time to grow, because if you accept being pushed in front of us and you are not ready your mistakes will cause frustration in professional orchestras. The problem is that some young conductors are promoted to these careers because they project “the right image”, and agencies have a lot of money to make from it.

9- what you do with your gestures has to match what we have in the part. If you are jumping like crazy and we have a sustained note ppp you are not helping us.

10- more energy doesn’t mean more sound or excitement. It is rather the moment when you give it. If you give us too much information all the time, too many movements, it can become overwhelming and we might end up disconnecting.

11- please LEAD.

12- please notice that “it is a dream to be here” [followed by some good 2 minutes of talking about themselves] is a speech we hear every time we get a new conductor (and some give the same time when they are re-invited). As someone said around here “Good morning ladies and gentleman. This week we have a beautiful program ahead of us. The plan today is Mahler, and after the break we will do only the third movement so the winds may leave. Mahler, first movement, please”.

13- if you have special requirements for bowings please do it ahead of time. Please, don’t use 5 minutes to sort out bowings with the concertmaster.

14- please make sure that we can all hear you. In the last stand of first violins perhaps there is an old lady who can’t hear as well as she could when she was 20 😉

15- please, in good professional orchestras, you don’t need to repeat a passage just to be sure that the musicians a small minor correction right. We most likely got it.

16- if someone in the winds is playing out of tune, please TELL THEM, and correct the intonation!

17- in general “less is more”. Save the best and for the really big momments it is a lot more effective.

18- please, communicate with your eyes. With your eyes you can show aproval, warn a section that they have an entrance after a long time without playing… what worked for Karajan (eyes closed) might not work for you.

I am sure some of colleagues would not agree. I have never ever stood on the podium nor held a baton, but that is the advice I can give you based on my experience of playing in student, amateur, youth, and professional orchestras (both in the pit and on the stage).

Finally, I wish you all the best of luck in your career. You have a beautiful profession. Do things in a smart way, and maybe some day I will have the pleasure of congratulating you (believe me, when the conductor is good and I feel “wow, that was a good concert” I do it). Perhaps then you will be too busy for that coffee!

Amen.

This all makes a lot of sense to me (except point 13: sometimes it is necessary to discuss bowings, just in order to find the best one). Thank you. They are good rules.

We had, about 17 years ago a very famous young conductor (one I am sure you have had lunch or a coffee with). He had written in his score highly personal bows he claimed were pass down to him by a very famous conductor (another one, now sadly deceased, with whom I am sure you have had lunch or coffee). If he had gone to the librarian in advance the bowings would had been in the parts and we wouldn’t had had to waste 15 minutes sorting out his bowings (which incidentally did not work that well). That’s what I mean.

This was wonderful, thank you!

When a musician asks for an “honest opinion” they are usually trolling for praise, especially after a concert.

Refreshing, since orchestras spend too much of their time saying what’s wrong with young conductors.

I feel the letter signed by the young conductor seems to be sincere. He most probably looks for help in his/her young age, and as any young professional in any profession, deserves to be guided.

Comments from “Frau Geigerin” could be seen/read/felt as too harsh, but not many participants in this chain of dialogues seem to have been or to be (presently) playing in orchestras. So with all due respect, I would perhaps doubt that most people making opinions have the practical knowledge she surely has.

If I were to give my opinion on a known issue -that absolutely everybody had/has to go through when starting a career-, I would just ask me/you/everyone the following questions: How many Mozart Sonatas have a young conductor played before his/her first conducted Mozart symphony? How many Bach suites, partitas, fugues, sonatas before conducting his/her first Bach Cantata/Passion/Brandeburg? how many Beethoven pieces has she/he played before conducting his/her first Beethoven symphonies? how many years of chamber music has she/he played before stepping on a podium? how many singers in how many lieder/arie has she/he accompanied before conducting her/his first opera? how many hours per week in how many years of practicing any string instrument has she/he played before making any comment on bowings to any concertmaster? this very short list, I understand, would be impressively long and boring if you apply the general concept to all possible music written by so many composers you have to actually understand and physically play before you try to conduct it, at least in your brain, without any musician in front of you……to say the least, just understanding that “X” or “Y” piece by some composers is a hard job -you need tenths of hours. And conversely, the powers of experience are similarly (comically) so ominous that the more you have musically done before you are stepping up the podium, the freer and more confident you will be in saying the words you need to say in front of anybody….you will just react to your ears because you spent your young life *making music*. And then…you need to find the way to audition, to work, to be hired as Korrepetitor/ Chorus master/ assistant/suggeritore/ whatever and then, only then, you start your schooling in conducting!…God knows that even the middle age conductors passed through some conservatory or university. But the impressive, fabulous weight of your own experience (and I usually show it with the following metaphor) shows when you entered the ship just as a poor sailor, young, and hopeful, and were sent to the very last engine room, and were ordered to clean it, to put oil on it, to say hi to the other sailors, then you had your first swet, month by month you were going up every level and tried to do all possible jobs in that ship, sharing all responsibilities and getting to understand all types of abilities that sailors need…then you get your pay: many years after you entered the ship, you are finally named Captain, and most probably, if you read and understood Seneca, you will do a good job -for you know the entire ship.

Sorry took me so long. We the old guys from the old school did this. I am utterly sorry that young kids think that everything comes from holding a baton in a nice manner. I am also sorry for the many Frauen-mit-Geige that need to go through discomfort after many years of playing. I am very sorry for the two sides of the coin, the two ends of the same table. I just feel that the decadence is already felt, seen, and not many people are totally aware of it. Most probably both the young conductor and Frau Geigerin could talk and write many more letters….but deep inside, we musicians know that the new school of show business, great appeal, flirting image, and very limited knowledge of the score, is all **wrong**. it is completely empty, banal, and today is totally out of control. It is a big failure of our culture…everybody should do something about it…..soon….

Apologies for the mistake. “5-year degree” and “major conservatory” led me strongly in that direction…then again, I am surprised that you seem to not count your own orchestra as a public one. So possibly no union, and no one to stop the conductor. If that is so, I am very sorry!

I appreciate you taking the time to answer in such detail, and very much agree with your list. General advice is important, as is the personal critique. If, in the future, you do get the chance to reach out to a conductor with specific suggestions, that would be a wonderful, additional step.

Conductors tend to live in very strange bubbles, whether they like it or not. If you are the one who manages to create a connection, leading to a serious and honest conversation, I beg you, do it. Maybe you can trust the words of Fabio Luisi, as well…

Thank you for treating this topic in such a positive manner. It showed me a new side of you and I will remember it when you publicly offend me the next time. Today, we both value our anonymity, but usually you are the only one of the two of us who enjoys that luxury. If it wasn’t for that, you should know that there isn’t such a thing as being too busy for a cup of coffee. 🙂

I joined a British orchestra in the seventies as a very young player and was really impressed by a young conductor on the podium, but at the same time appalled at the arrogance and rudeness displayed by, it has to said, some more senior members of the orchestra. ‘He is only a trumped up percussion player’ was one of the comments which really upset me. That aspiring young conductor was Simon Rattle, yes a percussionist as well, and no doubt a very good one.

Rattle has also said that he had a lot to learn when he started, and made plenty of mistakes in the early days.

One interesting comment he has made is that for a long time he declined invitations from the Berlin Phil to conduct them since, at the time, he felt he wasn’t ready.

I am a young conductor too. I can see both points of view and I want to comment a particular issue.

I am a woman-conductor in my late 20, I always approach musicians after each difficult rehearsal and ask them questions (not too many, but the most important ones). Generally speaking I am quite demanding, but always polite. I also have enough humility to understand that I need help if I want to evolve as a conductor. Many of my colleges were completely shut down to any feedback from musicians, but it never happened in my life. I do not know the reason, but I have seen that too many times.