18 tips for a young conductor

NewsIn our Reader’s Comment of the Day, an orchestra veteran offers important advice to a young conductor, who asked for it.

1- please, educate yourself. Not only in music, but also in literature, arts and philosophy. We had a not-so-young conductor (now with a first class international career) in my first f/t position in a professional orchestra about 20 years conducting Strauss’ Dance that mentioned in the middle of the rehearsal that the libretto of Salome was written by Hofmannsthal. I couldn’t take seriously that man anymore [please see point 3].

2- don’t waste the orchestra’s time with your needs. And if you stop please tell us why. If you make a mistake just say “sorry, I think I can do this better”. And that’s it: we are all humans and make mistakes.

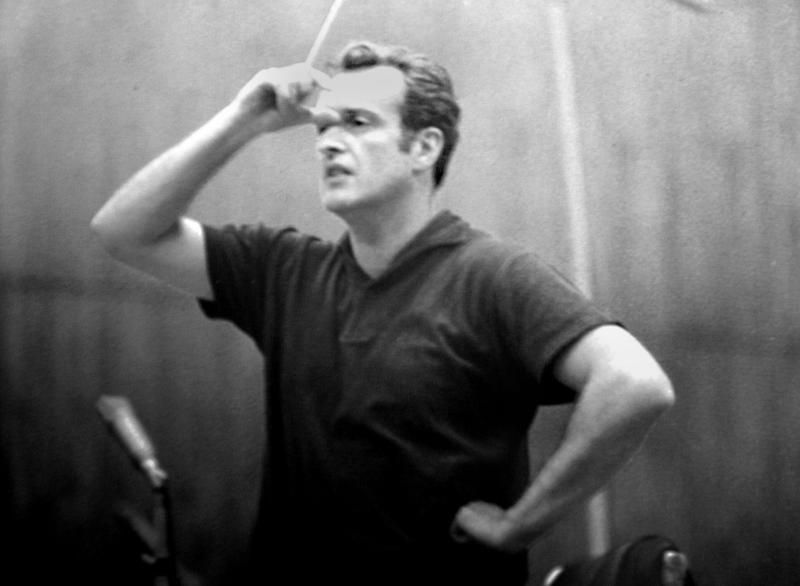

3- please, don’t talk too much. If you have good conducting technique that’s all you need. We can understand you better if you show what you want. And this brings us to…

4- know what you want. And plan your rehearsals (then it is very likely that the plan will change, but at least you have an idea of what you want to achieve).

5- please, finish in time the reahearsal. Some of us might be hungry, need to visit the restroom or pick up our children from school. In my orchestra we are very tolerant, but in some public orchestras musicians might just stand up and leave when the time is up. You have been warned

6- please don’t try to be original just for the sake of being different and unique. It is very likely we have played the standard repertoire many more times than you have conducted it. Please, build on that.

7- remember: we are there to make music. We (the orchestra) want to sound better and you can help us. That is your mission. Please, be the music, and be there for the music. Conducting should not be a way to make you feel “good” or important.

8- please, go step by step in your career. Don’t try to go from riding a bicycle with training wheels to piloting an airplane in 5 years. Earn your stripes in youth/community orchestras, assisting in opera, working as accompanist in opera…. give yourself time to grow, because if you accept being pushed in front of us and you are not ready your mistakes will cause frustration in professional orchestras. The problem is that some young conductors are promoted to these careers because they project “the right image”, and agencies have a lot of money to make from it.

9- what you do with your gestures has to match what we have in the part. If you are jumping like crazy and we have a sustained note ppp you are not helping us.

10- more energy doesn’t mean more sound or excitement. It is rather the moment when you give it. If you give us too much information all the time, too many movements, it can become overwhelming and we might end up disconnecting.

11- please LEAD.

12- please notice that “it is a dream to be here” [followed by some good 2 minutes of talking about themselves] is a speech we hear every time we get a new conductor (and some give the same time when they are re-invited). As someone said around here “Good morning ladies and gentleman. This week we have a beautiful program ahead of us. The plan today is Mahler, and after the break we will do only the third movement so the winds may leave. Mahler, first movement, please”.

13- if you have special requirements for bowings please do it ahead of time. Please, don’t use 5 minutes to sort out bowings with the concertmaster.

14- please make sure that we can all hear you. In the last stand of first violins perhaps there is an old lady who can’t hear as well as she could when she was 20

15- please, in good professional orchestras, you don’t need to repeat a passage just to be sure that the musicians a small minor correction right. We most likely got it.

16- if someone in the winds is playing out of tune, please TELL THEM, and correct the intonation!

17- in general “less is more”. Save the best and for the really big momments it is a lot more effective.

18- please, communicate with your eyes. With your eyes you can show aproval, warn a section that they have an entrance after a long time without playing… what worked for Karajan (eyes closed) might not work for you.

I am sure some of colleagues would not agree. I have never ever stood on the podium nor held a baton, but that is the advice I can give you based on my experience of playing in student, amateur, youth, and professional orchestras (both in the pit and on the stage).

Finally, I wish you all the best of luck in your career. You have a beautiful profession. Do things in a smart way, and maybe some day I will have the pleasure of congratulating you (believe me, when the conductor is good and I feel “wow, that was a good concert” I do it). Perhaps then you will be too busy for that coffee!

Comments